The GENIUS Act, signed into law on July 18, establishes a comprehensive regulatory framework for stablecoins in the US and is the first major US law specifically designed to regulate a crypto asset. The Act has significant implications for not only the stablecoin market but also the crypto ecosystem and financial sector. It also represents just one step in a broader effort to establish a comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets in the US. With the signing of the GENIUS Act (“the Act”) into law on July 18, the US has established a new regulatory regime for stablecoins, a kind of crypto asset designed to maintain a peg to a fiat currency, typically the US dollar. Creating a stablecoin regulatory framework has been a priority for policymakers for several years, motivated by high-profile events that resulted in consumer losses, concerns of contagion between crypto firms and banks, and accusations of fraud. However, years-long Congressional negotiations had failed to resolve disagreements about key issues, including the relative roles of Federal and state regulators, the scope of consumer protections, and the composition of permitted reserve assets. Passage of the Act comes at a pivotal time for crypto industry – crypto asset values have increased substantially in recent months, the Administration has advanced pro-crypto policies, and Congress continues work on “market structure” legislation that would establish a regulatory framework for the broader crypto asset industry. However, it remains to be seen whether this will usher in a new era in which crypto becomes an integral part of the larger financial system or whether it will remain a niche technology with limited real-world applications. The Act establishes a comprehensive regulatory framework for the issuance and oversight of payment stablecoins in the US. According to the Act, only “permitted payment stablecoin issuers” may issue stablecoins in the US, which includes subsidiaries of insured depository institutions (i.e., banks or credit unions), nonbank entities approved by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) or a state stablecoin regulator, and uninsured national banks chartered and approved by the OCC. Notably, the Act also limits the ability of public non-financial companies – including wholly or majority owned subsidiaries – from issuing stablecoins without an exemption granted by a new Stablecoin Certification Review Committee. This measure is intended to respond to concerns that the entry of large technology and social media firms, e.g., Meta, into the stablecoin market could raise market concentration and consumer privacy concerns. The Act also prohibits digital asset service providers from offering or selling stablecoins issued by entities not permitted under the Act and from facilitating secondary trading of stablecoins issued by foreign entities not in compliance with the Act. The Act prohibits foreign issuers from offering stablecoins in the US unless the issuer complies with the terms of the Act, is subject to a foreign regulatory regime that the Secretary of the Treasury determines is “comparable” to that established by the Act, registers with the OCC, the reserves backing the stablecoin are held in a US financial institution (unless otherwise permitted by a reciprocal agreement between the US and the issuer’s home jurisdiction), and the issuer’s home jurisdiction is not subject to US economic sanctions or has heightened money laundering concerns. The Act also permits the Secretary of the Treasury to enter into reciprocal agreements with other jurisdictions regarding the regulation and supervision of foreign stablecoin issuers. The Act assigns regulatory authority over stablecoin issuers according to the issuer type, its charter, and the outstanding issuance value of its stablecoin. The OCC may issue a waiver to allow a State chartered issuer with more than $10 billion outstanding to remain under State supervision in certain circumstances. Currently only two issuers – Circle and Tether – have issuance exceeding $10 billion. The Act also creates a new interagency body – the Stablecoin Certification Review Committee (SCRC) – comprising the Secretary of the Treasury, the Chair of the Federal Reserve Board (or, if delegated, the Vice Chair for Supervision), and the Chair of the FDIC. The SCRC has several roles, including: Issuers are required to maintain one-to-one reserves backing their outstanding stablecoins. The Act specifies which assets are eligible reserves, which are limited to cash and other highly liquid assets based on US Treasury debt, including Treasury debt with maturities of 93 days or less, reverse repurchase agreements collateralized by Treasury debt, and tokenized forms of such reserves. The Act also requires regulators to issue rules on reserve asset diversification, including limits on deposit concentrations at banks, and standards for managing interest rate risk. The Act prohibits issuers from paying interest – including yield paid in cash or tokens – to stablecoin holders. The Act marks a watershed moment for the crypto industry – not only in its implications for stablecoins, but also as the first major Federal law specifically designed to regulate crypto. However, many questions remain about longer term impacts on crypto and financial markets, payments innovations, and the regulatory landscape for digital assets more broadly. Many experts believe that establishing a formal regulatory regime will accelerate broad adoption of stablecoins, facilitating significant innovations in payments and financial services. For example, stablecoins could offer instant and low-cost global payments that reduce risks and offer significant consumer benefits. In addition, programmable stablecoins could lower the cost of conditional payments that currently rely on escrow services. In the view of some crypto proponents, stablecoins could also catalyze the development of on-chain financial infrastructure to support 24/7 trading and settlement of tokenized financial instruments and real-world assets. However, this transformation may take time if it happens at all. Existing payments and financial systems have evolved over decades and reflect deeply embedded factors – such as fragmented regulatory regimes (including in US banking as well as differences among international jurisdictions), entrenched business models, and long-standing consumer preferences – that can be slow to change. In establishing clear stablecoin regulatory and oversight requirements, policymakers aim to reduce risks to the financial system and consumers. However, increased adoption of even well-regulated stablecoins could unintentionally increase certain risks. For example, stablecoins could compete with traditional bank deposits, potentially prompting large-scale outflows from the banking system. This, in turn, could constrain credit availability and pose risks to financial stability. This risk may be mitigated somewhat by the Act’s prohibition on yield-bearing stablecoins, making them less optimal substitutes for deposits. In addition, the conversion of Federally-insured deposits in consumers’ individual account into pooled accounts held by stablecoin issuers – with balances that likely exceed the deposit insurance limit – may heighten risks to both financial stability and consumer protection. The question of master account access for non-traditional financial institutions has been the subject of ongoing debates, particularly in recent years as crypto-related firms have sought access to the banking system. Seeking to clarify its process for evaluating requests for master accounts, in 2022 the Federal Reserve Board announced guidelines that organized firms into three risk tiers based on their characteristics. Institutions that are not Federally insured and not subject to Federal prudential regulation – a category that currently describes most stablecoin issuers – are in the highest risk tier. Institutions in this category are rarely approved for master accounts, a fact that has been the subject of ongoing litigation involving a Wyoming-chartered “Special Purpose Depository Institution” (SPDI) and criticism from some lawmakers. The Act does not directly address Federal Reserve master account access for stablecoin issuers, leaving such decisions to the discretion of individual Federal Reserve banks under existing policy. However, by establishing a pathway for stablecoin issuers to obtain a Federal charter and supervision from OCC, the Act could prompt increased interest from non-traditional firms in seeking master account access to hold stablecoin reserves. This development may also reduce the appeal of state-chartered, non-bank structures – such as Wyoming’s SPDIs – because those entities are classified by the Federal Reserve as higher risk under its tiered access guidelines and thus face greater scrutiny in master account applications. In banning interest on stablecoin holdings, the Act has created a distinction between stablecoins used for payments and tokenized money market funds (MMFs), such as those offered by Franklin Templeton and BlackRock, held to generate yield. This regulatory distinction may make tokenized MMFs the preferred asset for users and institutions seeking on-chain yield, while positioning stablecoins primarily as transactional instruments. As a result, capital that might otherwise have been allocated to interest-bearing stablecoins could migrate toward tokenized MMFs, which offer regulated exposure to Treasury rates along with blockchain-based settlement. Passage of the GENIUS Act is just one piece of a broader effort to bring regulatory clarity to the crypto market. Congress continues to work on broader crypto market legislation that will clarify the respective jurisdictions of the Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission over various types of digital assets, with the House passing the CLARITY Act on July 17 and Senate Republicans introducing a discussion draft of parallel legislation on July 22. Taken together, these developments represent significant progress toward establishing a comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets in the US. Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Background

Key Provisions

Permitted Issuers

Foreign Issuers

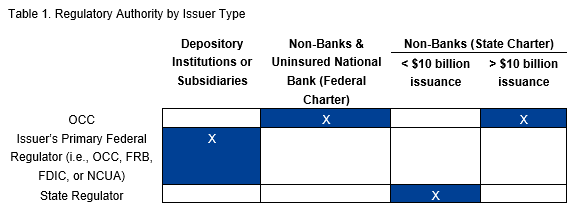

Regulatory Framework

Capital & Liquidity of Reserves

Interest

Potential Impacts

Innovation & Risk Reduction

Unintended Consequences

Master Account Access

Tokenized Money Market Funds

Conclusion