Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Medicare is a vital Federal health insurance program for the elderly and individuals with disabilities, providing coverage for hospital care, outpatient care, health care provider services, and prescription drugs for 67.6 million Americans. In 2024, the Medicare program had over $1.1 trillion in total expenditures, making it the largest health insurance program in the United States. Nevertheless, Medicare faces challenging headwinds as an aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary threaten its financial sustainability. These structural issues impact the Federal budget, the national debt, costs for beneficiaries, and reimbursement to providers as the Federal government, beneficiaries, and providers all struggle to adjust to imbalances in the current Medicare financing structure. Congress should act with urgency to ensure that scheduled benefits can be paid fully and that Medicare is available to meet the needs of its beneficiaries for generations to come.

This Explainer provides a description of the two Medicare Trust Funds and their current state; an overview of Medicare eligibility, benefits, supplemental coverage options, program revenues, and impact; a brief history of Medicare; and recent challenges and some recommendations for reform.

- Congress established the Medicare program in 1965 to provide health insurance to Americans 65 and older. In the ensuing decades, the program expanded eligibility, increased standardization and regulation, and added private health plan and prescription drug coverage to the program.

- Medicare benefits consist of three components: hospital insurance (Part A), medical insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage (Part D). After initial enrollment in Medicare, beneficiaries may choose to remain in Traditional Medicare to obtain Part A and/or Part B coverage or may opt to enroll in private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (Part C) to obtain their Medicare benefits.

- The Federal government has established two Trust Funds to track Medicare expenditures and revenues: the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund pays for Part A benefits while the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund pays for Part B and Part D benefits.

- Medicare eligibility is generally open to individuals aged 65 or older, individuals with a disability who receive Social Security Disability Insurance benefits, and individuals with end-stage renal disease.

- Cost-sharing is an important aspect of Medicare, with beneficiaries often responsible for paying premiums, deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. Because of these out-of-pocket costs, many Medicare beneficiaries choose to purchase supplemental coverage. Some MA plans are more comprehensive than Traditional Medicare and include other coverage.

- The primary revenue source for Part A coverage is a dedicated payroll tax on workers’ earnings. The main revenue sources for Part B and Part D coverage are contributions from the Federal government and premiums from beneficiaries.

- An aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary threaten the financial solvency of the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, with the Medicare Board of Trustees projecting the Fund’s insolvency in 2033. Government transfers and beneficiary premiums are also expected to rise to match rising Part B and Part D costs, putting pressure on Congress to enact reforms to restore the financial sustainability of the Medicare program.

Introduction

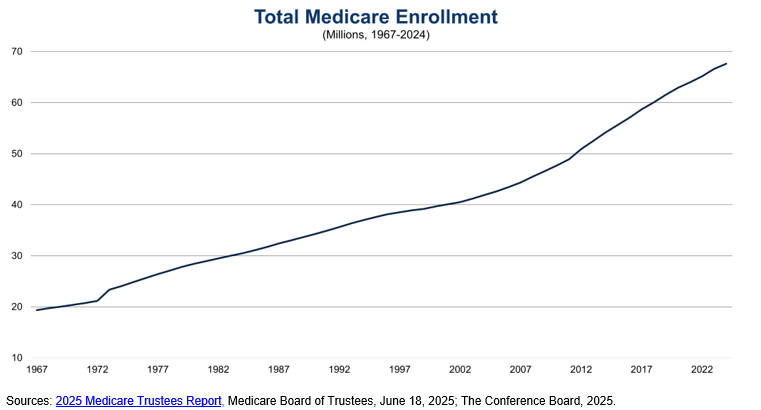

Medicare is a Federal health insurance program for the elderly and certain individuals with long-term disabilities that provides coverage for inpatient care in hospitals, provider and outpatient care, and prescription drugs. Congress established Medicare in 1965 to complement the Social Security program (see CED’s Explainer for more information on Social Security). More than 67 million Americans participate in Medicare and obtain health insurance benefits either through it or private health plans that administer their Medicare benefits, making Medicare a key part of the health care system in the United States.

Description of Medicare Trust Funds

Medicare has two Trust Funds that the program uses to pay for health care for enrollees:

- The Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund pays for inpatient hospital services, hospice care, skilled nursing facility services, and home health services after a hospital stay (known as “Part A” benefits). Payroll taxes on employers and employees are the primary revenue source for the HI Trust Fund. In 2024, HI Trust Fund total revenue was $451.2 billion and total expenditures were $422.5 billion.

- The Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund pays for provider (including physician), outpatient hospital, home health care, and other services (known as “Part B” benefits), as well as prescription drug coverage (known as “Part D” benefits). The major sources of revenue for the SMI Trust Fund are appropriations from the General Fund of the Treasury and premiums from enrollees. In 2024, SMI Trust Fund revenues across both Part B and Part D were $682.2 billion and total expenditures were $699.6 billion. Reserves of $170.5 billion at the end of 2024, held as assets in the SMI Trust Fund, covered the remaining balance.

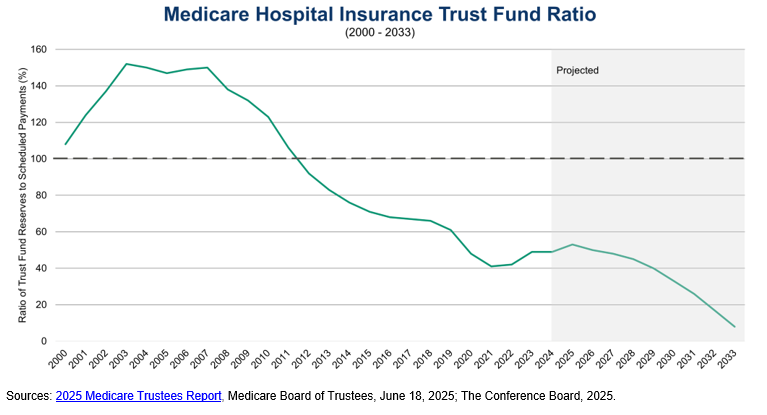

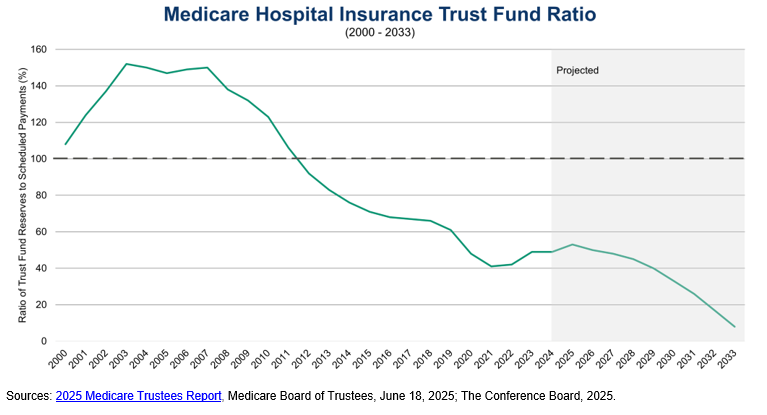

Since 2007, the HI Trust Fund balance as a percentage of annual expenditures has declined significantly, with the Medicare Board of Trustees projecting the depletion of the assets in the HI Trust Fund in 2033 absent legislative action. This financial challenge poses a significant threat to the Federal government’s ability to fully fund Medicare Part A benefits.

Brief History of Medicare

The idea for a national health insurance plan for the elderly started in 1945 under the Truman Administration. President Truman asked Congress for legislation establishing a national health insurance plan, though efforts to establish one were not successful. In the ensuing two decades, the elderly population grew from 12 million in 1950 to 17.5 million in 1963, representing almost 10 percent of the US population. Private health insurers struggled to provide comprehensive, affordable health care coverage to the elderly population during this time, particularly because of rising health care costs. In the early 1960s, the debate over health care for the elderly became more prominent in Congress, culminating in the Social Security Amendments of 1965. President Johnson signed the legislation establishing the Medicare program, which comprised Traditional Medicare (Part A and Part B) and limited eligibility to Americans aged 65 and older. President Truman and his wife Bess were the first Americans to receive Medicare cards in recognition of their dedication to establish a national healthcare plan for the elderly.

In 1972, President Nixon signed legislation expanding Medicare coverage to SSDI recipients with disabilities and to individuals with end-stage renal disease. In the 1980s, the Federal government began regulating and standardizing Medigap plans, added hospice coverage to Medicare Part A, and introduced programs like MSPs to reduce cost-sharing for low-income Medicare enrollees and Medicare HMOs. The late 1990s and early 2000s brought significant reforms to Medicare. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 created Medicare Advantage, then known as “Medicare+Choice”, with these plans going into effect in 1999. The next major reform was the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003, which established Medicare Part D effective January 1, 2006. The MMA formally designated all Medicare private health insurance coverage options as Part C and established regional PPOs and SNPs, and regulations issued under the Act formalized the system of plans submitting competitive bids to participate in Medicare Advantage.

More recently, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 added Medicare coverage for preventive care and health screenings free-of-charge to beneficiaries as well as reduced the out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 authorized Medicare to negotiate directly with drug companies to reduce the cost of and improve access to certain high expenditure, single source drugs without generic or biosimilar competition. The IRA also capped prescription drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries, with insulin products capped at $35 per month and Part D annual out-of-pocket prescription drug costs capped at $2,000 starting in 2025 (Congress exempted orphan drugs from price negotiations in Public Law 119-21 (H.R. 1, 2025), also referred to as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” or OBBBA, in 2025) .

Overview of the Medicare Program

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for administering the Medicare program (as well as Medicaid). The Social Security Administration (SSA) plays an important role in determining Medicare eligibility and enrolling beneficiaries as well as withholding Part B premiums from the Social Security benefits of most Medicare beneficiaries. Congress also established the Medicare Board of Trustees – consisting of the Treasury Secretary, Labor Secretary, Health and Human Services Secretary, Commissioner of Social Security, and two public representatives appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate – to oversee the financial operations of the HI and SMI Trust Funds and report annually to Congress on their financial and actuarial status. Medicare’s actual delivery of benefits relies on a health care system comprising private health plans, hospitals, physicians, other medical providers, and contractors that process claims.

Eligibility

Medicare eligibility, specifically for premium-free Part A (hospital insurance), is primarily based on one of three factors: being age 65 or older, having a disability, or having permanent kidney failure (end-stage renal disease). Individuals enrolling in Medicare based on age must be 65 or older and be eligible for monthly Social Security or Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) cash benefits and must enroll in a specific period around their 65th birthday or face a penalty. This eligibility is tied to a specific number of quarters of coverage earned though the payment of payroll taxes during an individual’s working years, typically equivalent to at least 10 years of payments. Individuals can also apply for Medicare if their spouse or child is eligible for Social Security or RRB benefits.

Individuals younger than 65 are eligible for Medicare Part A if they have been entitled to Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits for 24 months. Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) are entitled to receive Medicare Part A with no waiting period. Individuals with end-stage renal disease are also eligible for Medicare Part A if they worked the required amount of time under Social Security, are eligible for Social Security or RRB benefits, or are the spouse or dependent child of a person who has worked the required amount time or is eligible for Social Security.

Individuals who do not qualify based on the above factors may be able to pay a premium to enroll in Medicare Part A, though they must enroll during a designated enrollment period, and only about 1 percent of Medicare beneficiaries pay a Part A premium. Anyone eligible for premium-free Part A benefits can enroll in Medicare Part B by paying a monthly premium. Individuals aged 65 or older who are US citizens or who are permanent residents who have lived in the US for at least five years may enroll in Medicare Part B during designated enrollment periods as well. Following initial enrollment in the program, individuals eligible for Traditional Medicare (Part A or Part B, also known as “Original Medicare”) can obtain their benefits through a private health plan under the Medicare Advantage program (Part C) and can also obtain Medicare Part D prescription coverage. The premiums and coverage options for these benefits are discussed in more detail below.

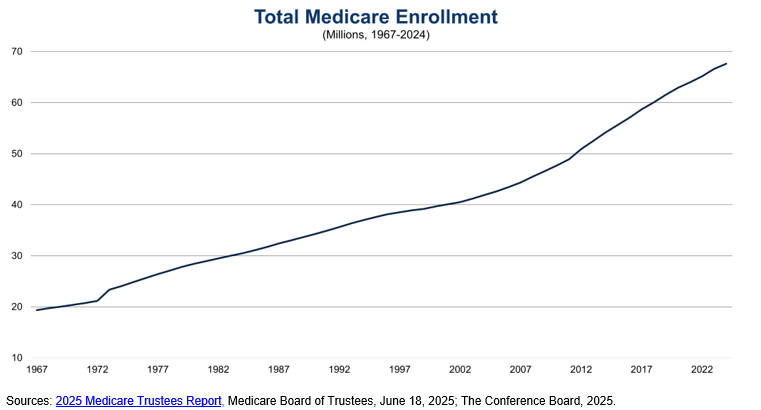

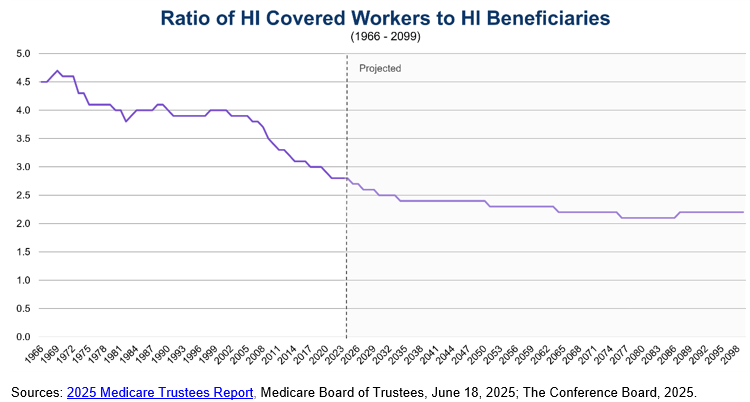

Figure 1: Total Medicare Enrollment (1967-2024)

Traditional Medicare Benefits (Part A and Part B)

Traditional Medicare is administered by the Federal government and consists of Part A and Part B:

- Part A (hospital insurance) covers certain home health services associated with an inpatient hospital visit, hospice care, inpatient hospital care, and skilled nursing facility care. Almost all Medicare beneficiaries do not pay a premium for Part A coverage; those that do pay a monthly premium in 2025 of either $285 or up to $518 depending on how long the individual or their spouse paid Medicare taxes (these premium amounts are not means-tested). Medicare beneficiaries are also responsible for copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles on Part A-covered services.

- Part B (medical insurance) covers medically necessary provider (including physician) services, outpatient care, certain other home health services, durable medical equipment, mental health services, and many preventive services. The standard Part B monthly premium is $185 in 2025. Individuals with a modified adjusted gross income of $106,000 (individual filers) or $212,000 (joint filers) in 2025 must also pay an extra charge known as the Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount, which can increase monthly premiums to as much as $628.90. Individuals may also be subject to a late enrollment penalty of 10 percent of the monthly Part B premium for each 12 months an individual did not sign up for Part B coverage when they were eligible. As with Part A, Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles on Part B-covered services, which are adjusted annually according to provisions of the Social Security Act.

Cost-sharing is an important component of Medicare Part A, particularly for inpatient hospital care and skilled nursing facility care. Medicare tracks hospital and skilled nursing facility use through a benefit period, which starts the day an individual is admitted as an inpatient to a hospital or skilled nursing facility and ends when that individual has not received inpatient care for 60 consecutive days. For the first 60 days of a benefit period of inpatient hospital care, beneficiaries only pay up to their Part A deductible, which is $1,676 in 2025. For days 61-90, beneficiaries are responsible for a daily $419 coinsurance amount. After 90 days, beneficiaries must pay a daily $838 coinsurance amount while using up to 60 lifetime reserve days, which may be applied to different hospital stays. Once those lifetime reserve days are used up, beneficiaries are responsible for 100 percent of inpatient hospital care costs.

The cost-sharing structure for skilled nursing facility care is similar. Medicare only covers skilled nursing facility care after a 3-day minimum medically necessary inpatient hospital stay. For each benefit period, beneficiaries do not pay copays for the first 20 days and are responsible for a $209.50 daily copayment for days 21-100 of their skilled nursing facility stay. After 100 days, Medicare enrollees are fully responsible for all costs of their skilled nursing facility stay.

Medicare Part B also institutes cost-sharing mechanisms for covered services. If the Part B annual deductible of $257 applies, beneficiaries must pay all costs up to the Medicare-approved amount until they meet the annual Part B deductible. Beyond the deductible, Medicare enrollees are typically responsible for paying 20 percent of the Medicare-approved amount. Crucially, there is no yearly out-of-pocket maximum for Traditional Medicare. While beneficiaries do not pay out-of-pocket for many preventive services, Traditional Medicare does not cover certain services like eye exams (it does cover medically necessary eye surgery), long-term care, hearing aids and exams for fitting them, and most dental care. As such, many Medicare beneficiaries purchase supplemental insurance or enroll in Medicare Advantage to lower their cost-sharing burden and obtain additional health care services.

Another important aspect of Traditional Medicare is fee-for-service payments to providers. Under this payment system, hospitals, physicians, and other medical providers submit a claim to the Medicare program for each service provided to a Medicare beneficiary. Medicare reimburses health care providers based on either a prospective payment system for inpatient stays tied to a diagnosis-related group or through fee schedules that are comprehensive lists of maximum fees to pay providers. Any provider that agrees to accept the Medicare-approved rate, known as “taking assignment,” may not request additional payments from the beneficiary or insurer (if the beneficiary is enrolled in Medicare Advantage or has supplemental coverage) above the annual deductible or coinsurance.

Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage (Part D)

To help pay for prescription drugs, Medicare beneficiaries can choose to enroll in Medicare Part D (prescription drug coverage). Medicare Part D, which went into effect in 2006, is an optional benefit that can be purchased during designated enrollment periods for an additional monthly premium. The base monthly premium for 2025 is $36.78, though the premium is typically adjusted depending on the Part D plan that the individual chooses. Beneficiaries may enroll in Part D plans from different providers and may change providers during specified open enrollment periods. As with Part B, there is a late enrollment penalty for joining a Part D plan after an individual’s eligibility date (unless an individual can demonstrate creditable prescription drug coverage) and there is an Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount for those with modified adjusted gross income of $106,000 (individual filers) or $212,000 (joint filers), which can raise monthly premiums by up to $85.80. Individuals who meet certain low-income or limited-resources requirements may also pay reduced premiums or no premiums at all.

Medicare enrollees may obtain Part D coverage through specially designed Medicare drug plans for those in Traditional Medicare or as part of their benefits under most Medicare Advantage health plans. While specific cost-sharing levels vary by plan, the standard Part D plan design has an initial deductible of $590 in 2025, with beneficiaries typically covering 25 percent of costs up to an out-of-pocket maximum of $2,000 in 2025. Beneficiaries receive manufacturer discounts for brand-name drugs and/or benefits for generic drugs from their Part D plans equivalent to 75 percent of costs until reaching the annual out-of-pocket maximum. After reaching this out-of-pocket maximum, all Part D enrollees receive catastrophic coverage and do not have to pay copayments or coinsurance for the rest of the calendar year. Under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, the out-of-pocket maximum of $2,000 for Part D enrollees will increase annually by the growth in average per capita Part D costs. Insulin products covered under Part D plans are not subject to the Part D deductible and are capped at a monthly $35 copayment under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Medicare Advantage (Part C)

In 2003, Congress enacted the Medicare Modernization Act. Since 2006 when the current program went into effect, Medicare enrollees may choose to obtain their Part A and Part B benefits through a Medicare Advantage plan, a private health insurance plan that CMS must approve to enroll Medicare beneficiaries and follow rules set by Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans provide all Part A and Part B benefits, except for hospice care, costs associated with kidney transplants, and certain clinical trial costs. Most Medicare Advantage plans also provide Part D coverage for prescription drugs. Additionally, these private plans may offer extra benefits outside of Traditional Medicare, such as vision, hearing, dental, and transportation services. Enrollees can choose to join, drop, switch, or make changes to their Medicare Advantage plan during designated enrollment periods throughout the year.

Medicare pays Medicare Advantage plans on a capitated basis, which means that Medicare pays these health insurers a fixed, predetermined amount on a per member per month basis. CMS bases these capitated payments on competitive bids by plans, their relationship to corresponding benchmarks from an annually developed rate book tied to estimated fee-for-service costs and the geographic, demographic, and risk characteristics of plan enrollees. Plans can also receive rebates according to their quality scores. The plans then have flexibility to set monthly premiums, annual deductibles, copayments or coinsurance, and maximum out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries within rules set by the Medicare program, which differ from Traditional Medicare. Given the capitated nature of Medicare Advantage, plans may require beneficiaries to obtain a referral to see a specialist, require pre-authorization before paying for certain drugs or services, or limit beneficiaries to providers within the plan’s network.

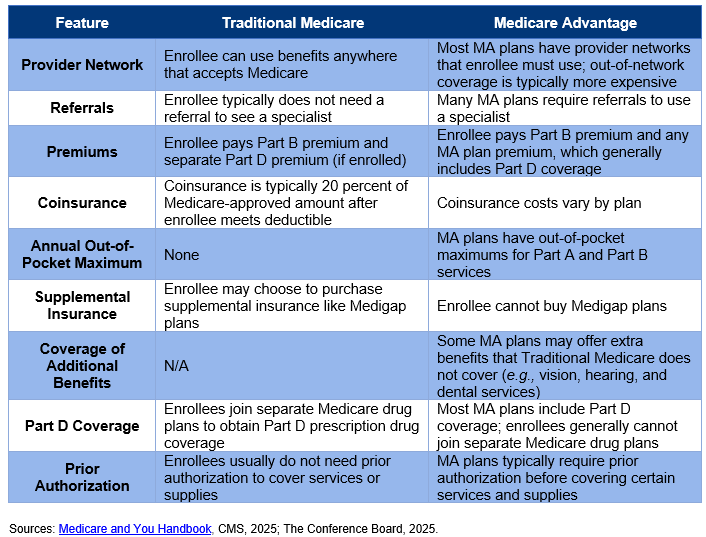

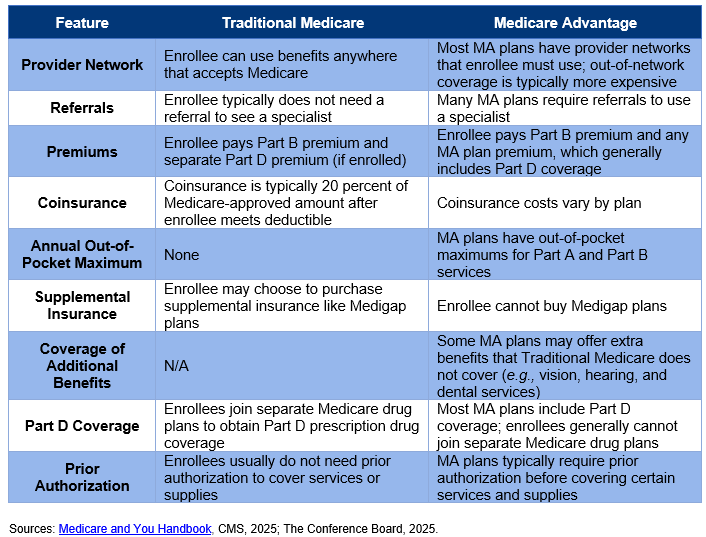

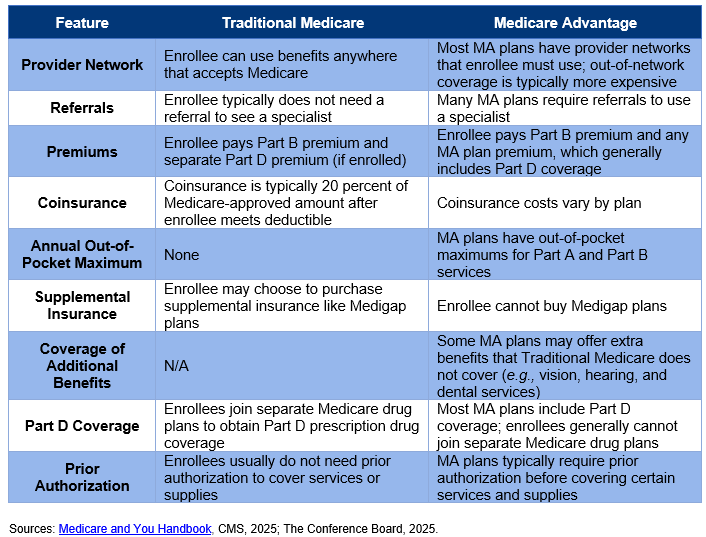

Figure 2: Comparison of Traditional Medicare vs. Medicare Advantage

There are four main types of Medicare Advantage plans that enrollees may choose to join:

- A Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan, pioneered in the 1980s, provides care exclusively from doctors, hospitals, and other medical providers within the plan’s network. There are certain exceptions, such as for emergency care, out-of-area urgent care, and temporary out-of-area dialysis. HMOs require referrals from a doctor to see a specialist. HMO Point-of-Service plans do offer an out-of-network benefit for some or all covered services, though these plans usually charge higher copayments and coinsurance for this benefit. Most Medicare HMO plans offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan also has a network of providers for their beneficiaries to use. Enrollees may obtain care from out-of-network providers that agree to treat the patient and have not opted out of Medicare Part A and Part B, but enrollees must usually pay higher cost-sharing fees to access these providers. Most PPO plans offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) plan is offered by a private health insurer that determines how much it will pay health care providers and how much beneficiaries will pay for each covered service, akin to a fee-for-service payment system. Some PFFS plans have provider networks for their plan members, with beneficiaries generally paying more for out-of-network providers who accept the plan’s payment terms. Only some PFFS offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Special Needs Plan (SNP) limits membership to one of three groups eligible for Medicare: individuals with severe or disabling chronic conditions, such as cancer, chronic heart failure, dementia, or HIV/AIDS; individuals who live in an institution or require a facility level of care; and individuals who are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. SNPs offer the same coverage that all Medicare Advantage Plans offer as well as extra services tailored to the specific groups they serve, such as specialists in the diseases or conditions for affected members and care coordinators. All SNPs must offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

Another type of plan is a Medicare Medical Savings Account (MSA) plan that combines a high-deductible health plan with a medical savings account. These plans set a high annual deductible before they begin covering a beneficiary’s costs. To assist beneficiaries with covering their medical costs, the MSA plan deposits money into a special savings account that can be used to pay for qualified medical expenses, such as Part A and Part B services. MSA plans generally do not have a network of providers, require referrals to see a specialist, have separate monthly premiums, or offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

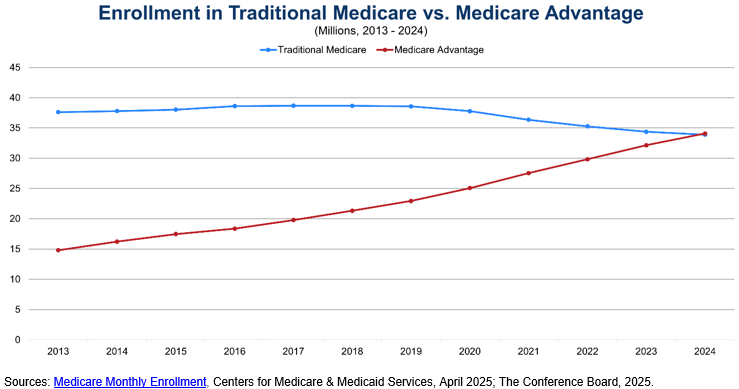

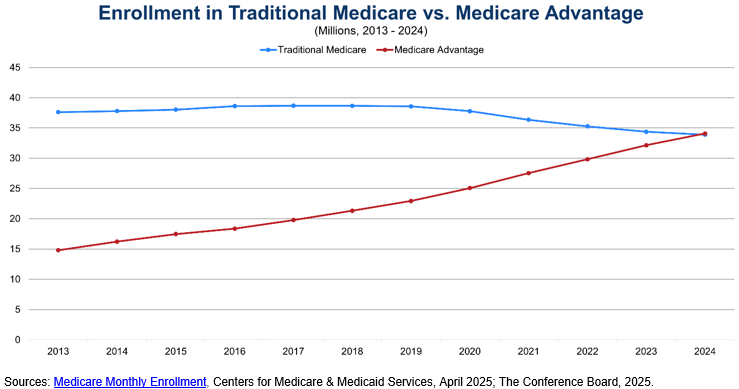

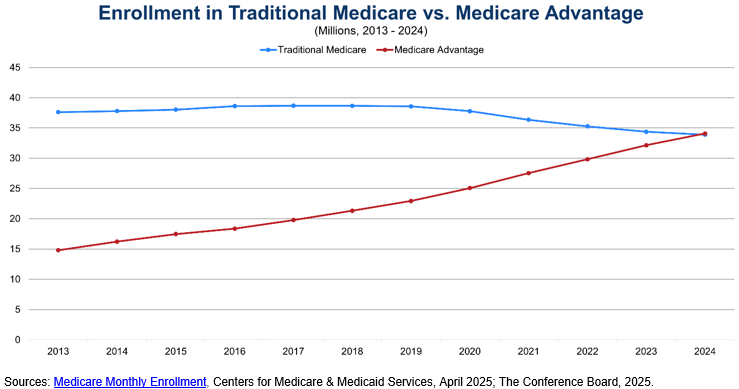

Figure 3: Half of Medicare Beneficiaries Are Enrolled in Medicare Advantage Plans

As shown above, half of Medicare beneficiaries have chosen to enroll in Medicare Advantage plans to obtain their Medicare benefits. This share has grown significantly over the past decade as the Federal government has encouraged private health plan participation in the program through stronger financial incentives after Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Medicare Advantage enrollment varies widely by state and county. UnitedHealthcare and Humana accounted for 47 percent of enrollment in 2023, highlighting the highly concentrated nature of the Medicare Advantage plan market. There are also more than 5.7 million Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in SNPs, with almost 90 percent enrolled in SNPs for dual eligibles (Medicaid). The number of SNP enrollees has doubled since 2018.

Supplemental Coverage for Medicare Beneficiaries

Given Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and the absence of a cap on out-of-pocket costs in Traditional Medicare, many Medicare beneficiaries choose to purchase supplemental insurance coverage to make their health care more affordable and meet all their health care needs. A popular option for supplemental coverage is Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap). Private health insurance companies offer these standardized policies to help cover a Medicare beneficiary’s out-of-pocket expenses, such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles. Some plans also offer additional benefits such as coverage for foreign travel emergencies. Only enrollees in Traditional Medicare may purchase Medigap policies, and these policies usually do not cover long-term care, vision or dental care, prescription drugs, or hearing aids.

Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) are another supplemental coverage option for Medicare beneficiaries. States offer these programs for enrollees with limited income and resources. There are four main types of MSPs. The Qualified Medicare Beneficiary Program pays for Part A and/or Part B premiums and covers all deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments for Medicare services. The Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary Program and the Qualifying Individual Program help pay Part B premiums. The Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals Program pays Part A premiums and is targeted towards individuals with a disability who return to work and who have lost their Social Security disability benefits and premium-free Part A.

To cover long-term care expenses, eligible beneficiaries often enroll in Medicaid, a health insurance program for low-income individuals jointly run by states and the Federal government. For these dual enrollees, Medicare pays for covered services first and most prescription drugs, with Medicaid paying for long-term care and additional services such as transportation, home and community-based services, and dental, vision, and hearing services (if covered by Medicaid in the individual’s state).

Employer-sponsored insurance can also provide supplementary coverage, though only 18 percent of large firms offer these retiree health benefits to their employees as of 2018.

Program Revenues and Trust Funds

Each component of Medicare has separate revenue streams that are deposited into its respective Trust Fund. Medicare Part A revenue is tracked within the HI Trust Fund, and Medicare Part B and Part D revenue is tracked within separate accounts of the SMI Trust Fund.

The primary source of revenue for the HI Trust Fund is payroll taxes. Employers and employees each pay a 1.45 percent tax on workers’ earnings under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). Self-employed individuals pay the full 2.9 percent payroll tax on their net earnings under the Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA). While the Internal Revenue Service allows self-employed individuals to deduct the employer-equivalent portion of their SECA contributions for Federal income tax purposes, some self-employed individuals are effectively taxed higher than those who work for an employer, posing a financial barrier to entrepreneurship. Additionally, high-income workers pay an additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on their earnings above $200,000 (for individual filers) and $250,000 (for joint filers) under a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In 2024, the Federal government collected $396.4 billion in Medicare payroll taxes for the HI Trust Fund.

The next largest source of revenue for the HI Trust Fund is the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits above a certain threshold. Social Security beneficiaries with incomes above $34,000 (individual filers) or $44,000 (joint filers) pay income taxes on up to 85 percent of their benefits, with the additional revenues from the taxation of more than the first 50 percent going to the HI Trust Fund. Revenue from the taxation of Social Security benefits totaled $39.8 billion in 2024. The assets in the HI Trust Fund are invested in Treasury securities, which earn interest that is deposited in the Trust Fund, totaling $7.2 billion in 2024. Finally, the HI Trust Fund receives Medicare Part A premium revenue from enrollees who do not qualify for premium-free Part A, which represented $5 billion in revenue in 2024 (there are other miscellaneous revenue sources that provided $2.8 billion in 2024).

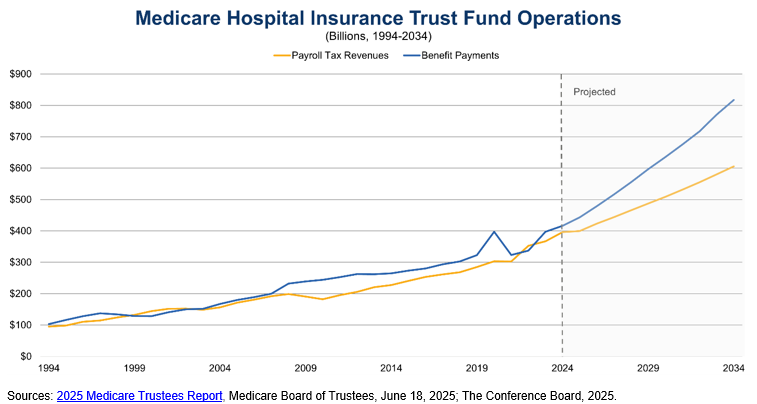

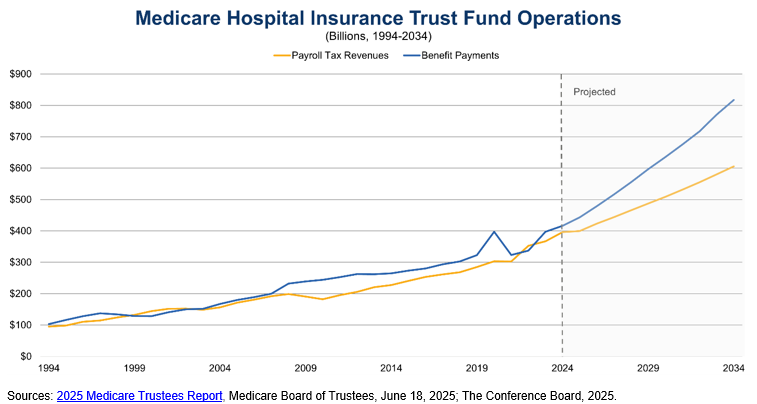

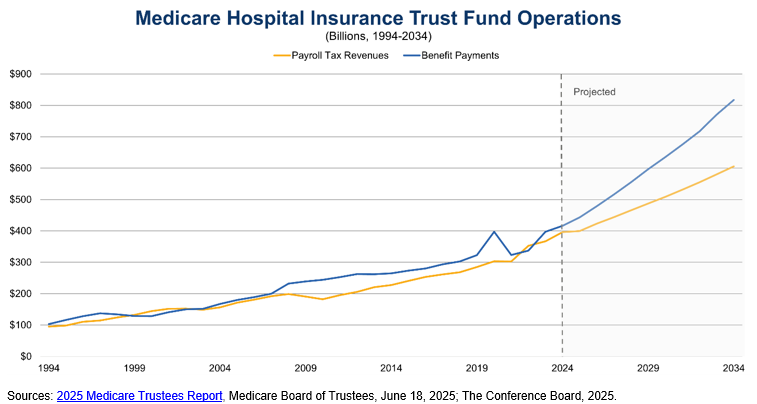

Figure 4: Payroll Tax Revenues vs. Medicare Part A Benefit Payments

For the SMI Trust Fund, the largest source of revenue is contributions from the Federal government. These transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury to the SMI Trust Fund totaled $497.6 billion in 2024, representing approximately 70 percent of program costs. The government contributions for the Part B program are based on a matching rate tied to premiums paid by Part B enrollees, with separate matching rates for enrollees who are aged 65 or older and those who have a disability. Part D government contributions are made on an as-needed basis to cover the portion of prescription drug expenditures that Medicare subsidies support. This constituted $111.6 billion in 2024 for Part D.

The next major source of SMI Trust Fund revenues is premiums from enrollees, $140.1 billion for Part B and $19.3 billion for Part D in 2024. States also make Part D payments for dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, which totaled $18 billion in 2024. As with the HI Trust Fund, the SMI Trust Fund earns interest on its assets invested in Treasury securities, representing $3.8 billion in 2024.

Current State of the Trust Funds

The HI Trust Fund and the SMI Trust Fund have different financing structures which impact how the Federal government considers the financial sustainability of each Trust Fund. The HI Trust Fund is meant to be self-financed through the dedicated funding source of payroll taxes, while the SMI Trust Fund relies on general tax revenues and beneficiary premiums. In its annual report to Congress, the Medicare Board of Trustees projects that the HI Trust Fund can only pay full scheduled Part A benefits until 2033 – three years earlier than the previous year’s projection – at which point Medicare will only be able to pay 89 percent of scheduled benefits when the reserves of the HI Trust Fund are depleted. For the SMI Trust Fund, the Medicare Board of Trustees projects full scheduled benefits will be payable indefinitely because government contributions and beneficiary premiums are adjusted annually to assist in covering expected program costs. However, the Medicare Board of Trustees remains concerned about the fast growth in Medicare Part B and Part D expenditures, which will put increasing pressure on the Federal government and beneficiaries to fund these rising costs through higher General Fund transfers and premiums, respectively.

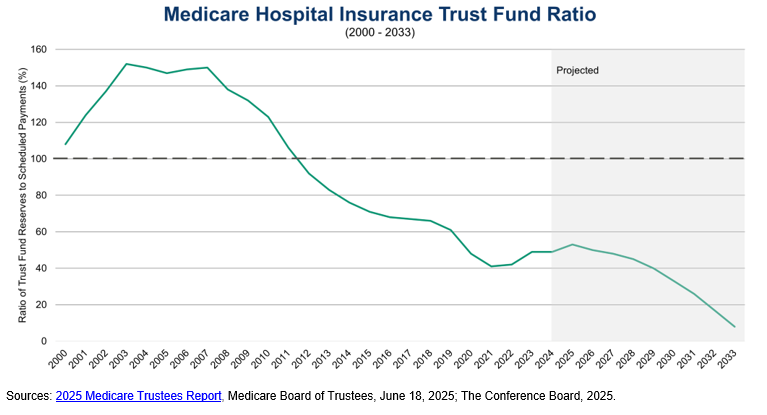

Figure 5: Projected Depletion of HI Trust Fund in 2033

Medicare’s Impact

Measured by expenditures, Medicare is the largest health care insurance program in the United States and the second largest social insurance program behind Social Security. In 2024, Medicare spent over $1.1 trillion on health care benefits for 67.6 million enrollees in both Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans. Given the vital role of Medicare in supporting the health care of our nation’s elderly population, Medicare remains popular with the American public. A 2023 poll showed that 81 percent of respondents had a favorable view of Medicare, with comparable levels of favorability across political parties and age groups. Nevertheless, more than 80 percent of respondents were worried that Medicare will not be able to continue to provide at least the same level of benefits in the future that it provides to seniors today. As a result, 73 percent of respondents believed changes need to be made to keep Medicare financially sustainable for the future, though only 59 percent of those older than 65 held this belief (Medicare’s financial challenges and CED’s policy recommendations are discussed further below).

Medicare also plays a significant role in funding medical residency training, also known as graduate medical education (GME). Medicare is the largest Federal source of GME funding, paying an estimated $16.2 billion for GME in Fiscal Year 2020, primarily to hospitals. These GME payments cover both the direct costs of operating a residency program as well as indirect costs that may result in higher patient care costs in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals. As such, Medicare is a crucial funding source for residency slots and thereby the overall physician workforce in the United States.

Recent Challenges and Urgent Need for Reform

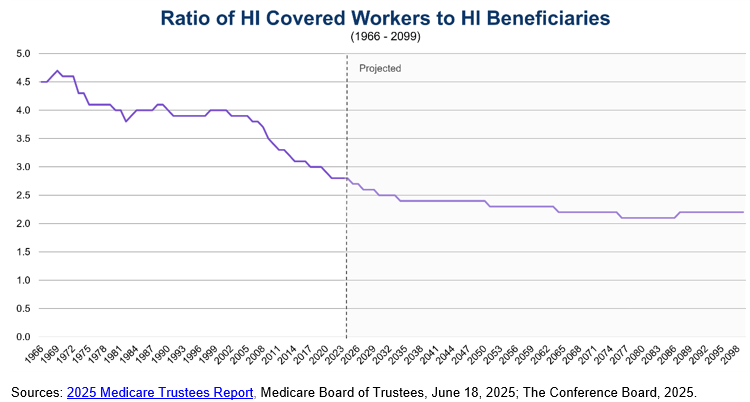

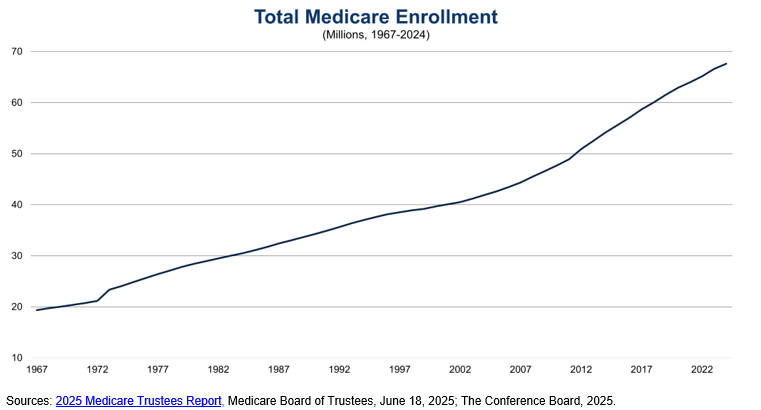

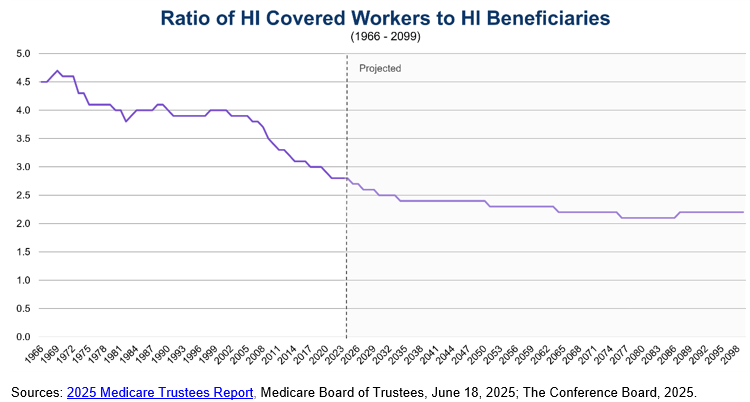

Medicare faces two main challenges related to long-term demographic trends and rising health care costs per beneficiary. The first challenge is an aging population, with members of the Baby Boom generation reaching Medicare eligibility in greater numbers. Combined with decreasing fertility rates and a proportionally smaller workforce to support payroll tax revenues, the number of workers per Medicare Part A beneficiary has declined dramatically over the past four decades, from approximately 4 workers per beneficiary in the period between 1980 and 2008 to 2.8 workers per beneficiary in 2024. The Medicare Board of Trustees projects this ratio to continue decreasing to 2.4 workers per beneficiary in 2034 before reaching only 2.2 workers per beneficiary in 2099. This disparity between Medicare beneficiaries and workers paying payroll taxes is a major reason for the short-term insolvency of the HI Trust Fund and its long-term negative actuarial balance (i.e., estimated income is insufficient to meet estimated HI Trust Fund obligations over the next 75 years).

Figure 6: Ratio of HI Workers per HI Covered Beneficiaries

The second financing challenge is rising health care costs per beneficiary. The United States already has the highest health care costs per capita compared to other advanced countries. The Medicare program is no exception – the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) projects Medicare Part A and Part B spending to grow by 4.5 percent annually after subtracting expected economy-wide inflation. This spending growth above and beyond inflation is primarily driven by the greater number of beneficiaries within the Medicare program and the volume and intensity of services used, particularly for Medicare Part B. Moreover, the number of older Americans over 80 is also expected to rise, from 25 percent of all seniors in 2020 to one-third of all seniors by 2060, sharply increasing the cost of care. MedPAC estimates spending per Medicare beneficiaries ages 85 and older was $17,600 in 2020 – driven by a greater number and complexity of health conditions that lead to higher ambulatory, inpatient, and prescription drug costs – compared to $10,100 for Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 to 74.

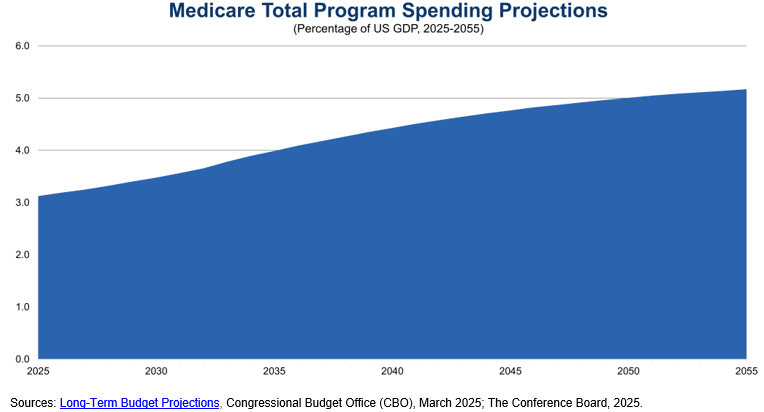

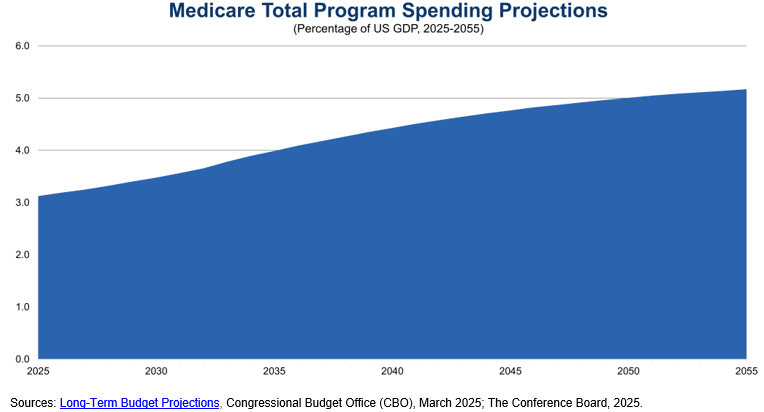

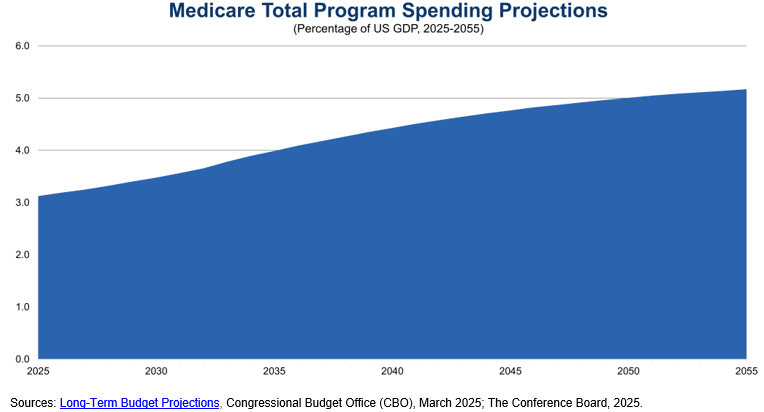

The US’s aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary put pressure on the Federal budget, which is already running sustained, record-breaking deficits. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects Medicare spending to increase by 2 percent of GDP over the next 30 years, reaching 5.2 percent of GDP in 2055. Medicare will account for over two-thirds of Federal spending on major health care programs (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and premium tax credits for health insurance purchased through Affordable Care Act marketplaces) in 2055. To finance this increasing spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities.

Figure 7: Projected Medicare Spending as a Percentage of GDP

A potential way to rein in rising Medicare costs is to promote Medicare Advantage plans. Traditional Medicare’s fee-for-service payment structure provides an incentive for health care providers to focus on volume of services delivered to generate reimbursement from the Medicare program. Medicare Advantage has a capitated payment structure, which gives health insurers a fixed payment per beneficiary. Medicare Advantage plans then have an incentive to promote quality and positive health care outcomes among beneficiaries and providers to retain as much of the capitated payment as possible, which can also be an incentive to limit care. MA plans cap annual out-of-pocket costs for Part A and Part B services and sometimes offer additional benefits, which make them attractive to some Medicare beneficiaries.

As Figure 3 demonstrates, enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans has surged in the past decade, and recent surveys of MA plan enrollees show almost 90 percent are satisfied with their health plan coverage. Nevertheless, a recent review of the literature comparing Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare showed few significant differences across measures of beneficiary experience, affordability, service utilization, and quality, demonstrating the need for continuing program improvements to realize the promise of Medicare Advantage. Stakeholders have also raised concerns about the MA program’s bidding benchmarks, risk adjustments, and quality rating systems contributing to overpayments to MA plans; the aggressive and potentially misleading marketing strategies of some MA plans; and the excessive use of prior authorization that delays care for beneficiaries and increases administrative burden for providers. As a result, CMS has increased its regulatory oversight of Medicare Advantage payment processes, marketing strategies, and prior authorization policies.

CED also has made several policy recommendations that Congress may wish to consider to slow the growth in Medicare spending:

- CMS should continue its implementation of value-based care and alternative payment models, including greater use of accountable care organizations.

- Congress, CMS, and health care providers should make upfront investments in workforce and data infrastructure to effectively and efficiently implement value-based care and alternative payment models.

- Congress should evaluate and reform the payment methodology for Medicare Advantage plans to affirm that the plans are generating savings for the Medicare program and delivering value and high-quality care to enrollees in Medicare Advantage.

- Congress, CMS, and health care providers should also emphasize primary care, preventive services, and care coordination to improve health outcomes and achieve savings in the long term.

- The CMS Innovation Center should regularly demonstrate to Congress and other policymakers that it is incorporating lessons learned from its testing of innovative payment and service delivery models to ensure value for money.

- The Administration and Congress should assess strategies to streamline regulations and payment policies that add costs and administrative burdens to the health care system.

Apart from a sizeable increase in the payroll tax, none of these options by themselves fully addresses the short-term and long-term challenges facing Medicare’s HI Trust Fund. As such, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which may include adjustments to premiums, cost-sharing, and prescription drug payments, and which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress should also protect vulnerable populations of older Americans by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide Americans approaching Medicare eligibility, health care providers, and health insurers sufficient time to adjust.

Conclusion

Medicare is a crucial health insurance program for the elderly and individuals with disabilities. Given the impending depletion in 2033 – an advance of three years from 2024 – of the HI Trust Fund that supports Part A coverage, it is vital that Congress address this issue quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to Medicare. The longer the delays, the greater the chance that necessary legislative changes to preserve Medicare will be disruptive to beneficiaries, health care providers, and the broader economy.

For Further Reading

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality, November 18, 2024

- CED’s Explainer, Medicaid, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, US National Debt, August 2025

- CED’s Policy Backgrounder, “Health Care Policy Update,” May 17, 2024

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, February 9, 2023

- “The Debt Crisis is Here,” Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray, November 13, 2023

Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Medicare is a vital Federal health insurance program for the elderly and individuals with disabilities, providing coverage for hospital care, outpatient care, health care provider services, and prescription drugs for 67.6 million Americans. In 2024, the Medicare program had over $1.1 trillion in total expenditures, making it the largest health insurance program in the United States. Nevertheless, Medicare faces challenging headwinds as an aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary threaten its financial sustainability. These structural issues impact the Federal budget, the national debt, costs for beneficiaries, and reimbursement to providers as the Federal government, beneficiaries, and providers all struggle to adjust to imbalances in the current Medicare financing structure. Congress should act with urgency to ensure that scheduled benefits can be paid fully and that Medicare is available to meet the needs of its beneficiaries for generations to come.

This Explainer provides a description of the two Medicare Trust Funds and their current state; an overview of Medicare eligibility, benefits, supplemental coverage options, program revenues, and impact; a brief history of Medicare; and recent challenges and some recommendations for reform.

- Congress established the Medicare program in 1965 to provide health insurance to Americans 65 and older. In the ensuing decades, the program expanded eligibility, increased standardization and regulation, and added private health plan and prescription drug coverage to the program.

- Medicare benefits consist of three components: hospital insurance (Part A), medical insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage (Part D). After initial enrollment in Medicare, beneficiaries may choose to remain in Traditional Medicare to obtain Part A and/or Part B coverage or may opt to enroll in private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (Part C) to obtain their Medicare benefits.

- The Federal government has established two Trust Funds to track Medicare expenditures and revenues: the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund pays for Part A benefits while the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund pays for Part B and Part D benefits.

- Medicare eligibility is generally open to individuals aged 65 or older, individuals with a disability who receive Social Security Disability Insurance benefits, and individuals with end-stage renal disease.

- Cost-sharing is an important aspect of Medicare, with beneficiaries often responsible for paying premiums, deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. Because of these out-of-pocket costs, many Medicare beneficiaries choose to purchase supplemental coverage. Some MA plans are more comprehensive than Traditional Medicare and include other coverage.

- The primary revenue source for Part A coverage is a dedicated payroll tax on workers’ earnings. The main revenue sources for Part B and Part D coverage are contributions from the Federal government and premiums from beneficiaries.

- An aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary threaten the financial solvency of the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, with the Medicare Board of Trustees projecting the Fund’s insolvency in 2033. Government transfers and beneficiary premiums are also expected to rise to match rising Part B and Part D costs, putting pressure on Congress to enact reforms to restore the financial sustainability of the Medicare program.

Introduction

Medicare is a Federal health insurance program for the elderly and certain individuals with long-term disabilities that provides coverage for inpatient care in hospitals, provider and outpatient care, and prescription drugs. Congress established Medicare in 1965 to complement the Social Security program (see CED’s Explainer for more information on Social Security). More than 67 million Americans participate in Medicare and obtain health insurance benefits either through it or private health plans that administer their Medicare benefits, making Medicare a key part of the health care system in the United States.

Description of Medicare Trust Funds

Medicare has two Trust Funds that the program uses to pay for health care for enrollees:

- The Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund pays for inpatient hospital services, hospice care, skilled nursing facility services, and home health services after a hospital stay (known as “Part A” benefits). Payroll taxes on employers and employees are the primary revenue source for the HI Trust Fund. In 2024, HI Trust Fund total revenue was $451.2 billion and total expenditures were $422.5 billion.

- The Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund pays for provider (including physician), outpatient hospital, home health care, and other services (known as “Part B” benefits), as well as prescription drug coverage (known as “Part D” benefits). The major sources of revenue for the SMI Trust Fund are appropriations from the General Fund of the Treasury and premiums from enrollees. In 2024, SMI Trust Fund revenues across both Part B and Part D were $682.2 billion and total expenditures were $699.6 billion. Reserves of $170.5 billion at the end of 2024, held as assets in the SMI Trust Fund, covered the remaining balance.

Since 2007, the HI Trust Fund balance as a percentage of annual expenditures has declined significantly, with the Medicare Board of Trustees projecting the depletion of the assets in the HI Trust Fund in 2033 absent legislative action. This financial challenge poses a significant threat to the Federal government’s ability to fully fund Medicare Part A benefits.

Brief History of Medicare

The idea for a national health insurance plan for the elderly started in 1945 under the Truman Administration. President Truman asked Congress for legislation establishing a national health insurance plan, though efforts to establish one were not successful. In the ensuing two decades, the elderly population grew from 12 million in 1950 to 17.5 million in 1963, representing almost 10 percent of the US population. Private health insurers struggled to provide comprehensive, affordable health care coverage to the elderly population during this time, particularly because of rising health care costs. In the early 1960s, the debate over health care for the elderly became more prominent in Congress, culminating in the Social Security Amendments of 1965. President Johnson signed the legislation establishing the Medicare program, which comprised Traditional Medicare (Part A and Part B) and limited eligibility to Americans aged 65 and older. President Truman and his wife Bess were the first Americans to receive Medicare cards in recognition of their dedication to establish a national healthcare plan for the elderly.

In 1972, President Nixon signed legislation expanding Medicare coverage to SSDI recipients with disabilities and to individuals with end-stage renal disease. In the 1980s, the Federal government began regulating and standardizing Medigap plans, added hospice coverage to Medicare Part A, and introduced programs like MSPs to reduce cost-sharing for low-income Medicare enrollees and Medicare HMOs. The late 1990s and early 2000s brought significant reforms to Medicare. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 created Medicare Advantage, then known as “Medicare+Choice”, with these plans going into effect in 1999. The next major reform was the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003, which established Medicare Part D effective January 1, 2006. The MMA formally designated all Medicare private health insurance coverage options as Part C and established regional PPOs and SNPs, and regulations issued under the Act formalized the system of plans submitting competitive bids to participate in Medicare Advantage.

More recently, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 added Medicare coverage for preventive care and health screenings free-of-charge to beneficiaries as well as reduced the out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 authorized Medicare to negotiate directly with drug companies to reduce the cost of and improve access to certain high expenditure, single source drugs without generic or biosimilar competition. The IRA also capped prescription drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries, with insulin products capped at $35 per month and Part D annual out-of-pocket prescription drug costs capped at $2,000 starting in 2025 (Congress exempted orphan drugs from price negotiations in Public Law 119-21 (H.R. 1, 2025), also referred to as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” or OBBBA, in 2025) .

Overview of the Medicare Program

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for administering the Medicare program (as well as Medicaid). The Social Security Administration (SSA) plays an important role in determining Medicare eligibility and enrolling beneficiaries as well as withholding Part B premiums from the Social Security benefits of most Medicare beneficiaries. Congress also established the Medicare Board of Trustees – consisting of the Treasury Secretary, Labor Secretary, Health and Human Services Secretary, Commissioner of Social Security, and two public representatives appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate – to oversee the financial operations of the HI and SMI Trust Funds and report annually to Congress on their financial and actuarial status. Medicare’s actual delivery of benefits relies on a health care system comprising private health plans, hospitals, physicians, other medical providers, and contractors that process claims.

Eligibility

Medicare eligibility, specifically for premium-free Part A (hospital insurance), is primarily based on one of three factors: being age 65 or older, having a disability, or having permanent kidney failure (end-stage renal disease). Individuals enrolling in Medicare based on age must be 65 or older and be eligible for monthly Social Security or Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) cash benefits and must enroll in a specific period around their 65th birthday or face a penalty. This eligibility is tied to a specific number of quarters of coverage earned though the payment of payroll taxes during an individual’s working years, typically equivalent to at least 10 years of payments. Individuals can also apply for Medicare if their spouse or child is eligible for Social Security or RRB benefits.

Individuals younger than 65 are eligible for Medicare Part A if they have been entitled to Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits for 24 months. Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) are entitled to receive Medicare Part A with no waiting period. Individuals with end-stage renal disease are also eligible for Medicare Part A if they worked the required amount of time under Social Security, are eligible for Social Security or RRB benefits, or are the spouse or dependent child of a person who has worked the required amount time or is eligible for Social Security.

Individuals who do not qualify based on the above factors may be able to pay a premium to enroll in Medicare Part A, though they must enroll during a designated enrollment period, and only about 1 percent of Medicare beneficiaries pay a Part A premium. Anyone eligible for premium-free Part A benefits can enroll in Medicare Part B by paying a monthly premium. Individuals aged 65 or older who are US citizens or who are permanent residents who have lived in the US for at least five years may enroll in Medicare Part B during designated enrollment periods as well. Following initial enrollment in the program, individuals eligible for Traditional Medicare (Part A or Part B, also known as “Original Medicare”) can obtain their benefits through a private health plan under the Medicare Advantage program (Part C) and can also obtain Medicare Part D prescription coverage. The premiums and coverage options for these benefits are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1: Total Medicare Enrollment (1967-2024)

Traditional Medicare Benefits (Part A and Part B)

Traditional Medicare is administered by the Federal government and consists of Part A and Part B:

- Part A (hospital insurance) covers certain home health services associated with an inpatient hospital visit, hospice care, inpatient hospital care, and skilled nursing facility care. Almost all Medicare beneficiaries do not pay a premium for Part A coverage; those that do pay a monthly premium in 2025 of either $285 or up to $518 depending on how long the individual or their spouse paid Medicare taxes (these premium amounts are not means-tested). Medicare beneficiaries are also responsible for copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles on Part A-covered services.

- Part B (medical insurance) covers medically necessary provider (including physician) services, outpatient care, certain other home health services, durable medical equipment, mental health services, and many preventive services. The standard Part B monthly premium is $185 in 2025. Individuals with a modified adjusted gross income of $106,000 (individual filers) or $212,000 (joint filers) in 2025 must also pay an extra charge known as the Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount, which can increase monthly premiums to as much as $628.90. Individuals may also be subject to a late enrollment penalty of 10 percent of the monthly Part B premium for each 12 months an individual did not sign up for Part B coverage when they were eligible. As with Part A, Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles on Part B-covered services, which are adjusted annually according to provisions of the Social Security Act.

Cost-sharing is an important component of Medicare Part A, particularly for inpatient hospital care and skilled nursing facility care. Medicare tracks hospital and skilled nursing facility use through a benefit period, which starts the day an individual is admitted as an inpatient to a hospital or skilled nursing facility and ends when that individual has not received inpatient care for 60 consecutive days. For the first 60 days of a benefit period of inpatient hospital care, beneficiaries only pay up to their Part A deductible, which is $1,676 in 2025. For days 61-90, beneficiaries are responsible for a daily $419 coinsurance amount. After 90 days, beneficiaries must pay a daily $838 coinsurance amount while using up to 60 lifetime reserve days, which may be applied to different hospital stays. Once those lifetime reserve days are used up, beneficiaries are responsible for 100 percent of inpatient hospital care costs.

The cost-sharing structure for skilled nursing facility care is similar. Medicare only covers skilled nursing facility care after a 3-day minimum medically necessary inpatient hospital stay. For each benefit period, beneficiaries do not pay copays for the first 20 days and are responsible for a $209.50 daily copayment for days 21-100 of their skilled nursing facility stay. After 100 days, Medicare enrollees are fully responsible for all costs of their skilled nursing facility stay.

Medicare Part B also institutes cost-sharing mechanisms for covered services. If the Part B annual deductible of $257 applies, beneficiaries must pay all costs up to the Medicare-approved amount until they meet the annual Part B deductible. Beyond the deductible, Medicare enrollees are typically responsible for paying 20 percent of the Medicare-approved amount. Crucially, there is no yearly out-of-pocket maximum for Traditional Medicare. While beneficiaries do not pay out-of-pocket for many preventive services, Traditional Medicare does not cover certain services like eye exams (it does cover medically necessary eye surgery), long-term care, hearing aids and exams for fitting them, and most dental care. As such, many Medicare beneficiaries purchase supplemental insurance or enroll in Medicare Advantage to lower their cost-sharing burden and obtain additional health care services.

Another important aspect of Traditional Medicare is fee-for-service payments to providers. Under this payment system, hospitals, physicians, and other medical providers submit a claim to the Medicare program for each service provided to a Medicare beneficiary. Medicare reimburses health care providers based on either a prospective payment system for inpatient stays tied to a diagnosis-related group or through fee schedules that are comprehensive lists of maximum fees to pay providers. Any provider that agrees to accept the Medicare-approved rate, known as “taking assignment,” may not request additional payments from the beneficiary or insurer (if the beneficiary is enrolled in Medicare Advantage or has supplemental coverage) above the annual deductible or coinsurance.

Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage (Part D)

To help pay for prescription drugs, Medicare beneficiaries can choose to enroll in Medicare Part D (prescription drug coverage). Medicare Part D, which went into effect in 2006, is an optional benefit that can be purchased during designated enrollment periods for an additional monthly premium. The base monthly premium for 2025 is $36.78, though the premium is typically adjusted depending on the Part D plan that the individual chooses. Beneficiaries may enroll in Part D plans from different providers and may change providers during specified open enrollment periods. As with Part B, there is a late enrollment penalty for joining a Part D plan after an individual’s eligibility date (unless an individual can demonstrate creditable prescription drug coverage) and there is an Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount for those with modified adjusted gross income of $106,000 (individual filers) or $212,000 (joint filers), which can raise monthly premiums by up to $85.80. Individuals who meet certain low-income or limited-resources requirements may also pay reduced premiums or no premiums at all.

Medicare enrollees may obtain Part D coverage through specially designed Medicare drug plans for those in Traditional Medicare or as part of their benefits under most Medicare Advantage health plans. While specific cost-sharing levels vary by plan, the standard Part D plan design has an initial deductible of $590 in 2025, with beneficiaries typically covering 25 percent of costs up to an out-of-pocket maximum of $2,000 in 2025. Beneficiaries receive manufacturer discounts for brand-name drugs and/or benefits for generic drugs from their Part D plans equivalent to 75 percent of costs until reaching the annual out-of-pocket maximum. After reaching this out-of-pocket maximum, all Part D enrollees receive catastrophic coverage and do not have to pay copayments or coinsurance for the rest of the calendar year. Under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, the out-of-pocket maximum of $2,000 for Part D enrollees will increase annually by the growth in average per capita Part D costs. Insulin products covered under Part D plans are not subject to the Part D deductible and are capped at a monthly $35 copayment under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Medicare Advantage (Part C)

In 2003, Congress enacted the Medicare Modernization Act. Since 2006 when the current program went into effect, Medicare enrollees may choose to obtain their Part A and Part B benefits through a Medicare Advantage plan, a private health insurance plan that CMS must approve to enroll Medicare beneficiaries and follow rules set by Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans provide all Part A and Part B benefits, except for hospice care, costs associated with kidney transplants, and certain clinical trial costs. Most Medicare Advantage plans also provide Part D coverage for prescription drugs. Additionally, these private plans may offer extra benefits outside of Traditional Medicare, such as vision, hearing, dental, and transportation services. Enrollees can choose to join, drop, switch, or make changes to their Medicare Advantage plan during designated enrollment periods throughout the year.

Medicare pays Medicare Advantage plans on a capitated basis, which means that Medicare pays these health insurers a fixed, predetermined amount on a per member per month basis. CMS bases these capitated payments on competitive bids by plans, their relationship to corresponding benchmarks from an annually developed rate book tied to estimated fee-for-service costs and the geographic, demographic, and risk characteristics of plan enrollees. Plans can also receive rebates according to their quality scores. The plans then have flexibility to set monthly premiums, annual deductibles, copayments or coinsurance, and maximum out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries within rules set by the Medicare program, which differ from Traditional Medicare. Given the capitated nature of Medicare Advantage, plans may require beneficiaries to obtain a referral to see a specialist, require pre-authorization before paying for certain drugs or services, or limit beneficiaries to providers within the plan’s network.

Figure 2: Comparison of Traditional Medicare vs. Medicare Advantage

There are four main types of Medicare Advantage plans that enrollees may choose to join:

- A Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan, pioneered in the 1980s, provides care exclusively from doctors, hospitals, and other medical providers within the plan’s network. There are certain exceptions, such as for emergency care, out-of-area urgent care, and temporary out-of-area dialysis. HMOs require referrals from a doctor to see a specialist. HMO Point-of-Service plans do offer an out-of-network benefit for some or all covered services, though these plans usually charge higher copayments and coinsurance for this benefit. Most Medicare HMO plans offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan also has a network of providers for their beneficiaries to use. Enrollees may obtain care from out-of-network providers that agree to treat the patient and have not opted out of Medicare Part A and Part B, but enrollees must usually pay higher cost-sharing fees to access these providers. Most PPO plans offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) plan is offered by a private health insurer that determines how much it will pay health care providers and how much beneficiaries will pay for each covered service, akin to a fee-for-service payment system. Some PFFS plans have provider networks for their plan members, with beneficiaries generally paying more for out-of-network providers who accept the plan’s payment terms. Only some PFFS offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

- A Special Needs Plan (SNP) limits membership to one of three groups eligible for Medicare: individuals with severe or disabling chronic conditions, such as cancer, chronic heart failure, dementia, or HIV/AIDS; individuals who live in an institution or require a facility level of care; and individuals who are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. SNPs offer the same coverage that all Medicare Advantage Plans offer as well as extra services tailored to the specific groups they serve, such as specialists in the diseases or conditions for affected members and care coordinators. All SNPs must offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

Another type of plan is a Medicare Medical Savings Account (MSA) plan that combines a high-deductible health plan with a medical savings account. These plans set a high annual deductible before they begin covering a beneficiary’s costs. To assist beneficiaries with covering their medical costs, the MSA plan deposits money into a special savings account that can be used to pay for qualified medical expenses, such as Part A and Part B services. MSA plans generally do not have a network of providers, require referrals to see a specialist, have separate monthly premiums, or offer Part D prescription drug coverage.

Figure 3: Half of Medicare Beneficiaries Are Enrolled in Medicare Advantage Plans

As shown above, half of Medicare beneficiaries have chosen to enroll in Medicare Advantage plans to obtain their Medicare benefits. This share has grown significantly over the past decade as the Federal government has encouraged private health plan participation in the program through stronger financial incentives after Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Medicare Advantage enrollment varies widely by state and county. UnitedHealthcare and Humana accounted for 47 percent of enrollment in 2023, highlighting the highly concentrated nature of the Medicare Advantage plan market. There are also more than 5.7 million Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in SNPs, with almost 90 percent enrolled in SNPs for dual eligibles (Medicaid). The number of SNP enrollees has doubled since 2018.

Supplemental Coverage for Medicare Beneficiaries

Given Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and the absence of a cap on out-of-pocket costs in Traditional Medicare, many Medicare beneficiaries choose to purchase supplemental insurance coverage to make their health care more affordable and meet all their health care needs. A popular option for supplemental coverage is Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap). Private health insurance companies offer these standardized policies to help cover a Medicare beneficiary’s out-of-pocket expenses, such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles. Some plans also offer additional benefits such as coverage for foreign travel emergencies. Only enrollees in Traditional Medicare may purchase Medigap policies, and these policies usually do not cover long-term care, vision or dental care, prescription drugs, or hearing aids.

Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) are another supplemental coverage option for Medicare beneficiaries. States offer these programs for enrollees with limited income and resources. There are four main types of MSPs. The Qualified Medicare Beneficiary Program pays for Part A and/or Part B premiums and covers all deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments for Medicare services. The Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary Program and the Qualifying Individual Program help pay Part B premiums. The Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals Program pays Part A premiums and is targeted towards individuals with a disability who return to work and who have lost their Social Security disability benefits and premium-free Part A.

To cover long-term care expenses, eligible beneficiaries often enroll in Medicaid, a health insurance program for low-income individuals jointly run by states and the Federal government. For these dual enrollees, Medicare pays for covered services first and most prescription drugs, with Medicaid paying for long-term care and additional services such as transportation, home and community-based services, and dental, vision, and hearing services (if covered by Medicaid in the individual’s state).

Employer-sponsored insurance can also provide supplementary coverage, though only 18 percent of large firms offer these retiree health benefits to their employees as of 2018.

Program Revenues and Trust Funds

Each component of Medicare has separate revenue streams that are deposited into its respective Trust Fund. Medicare Part A revenue is tracked within the HI Trust Fund, and Medicare Part B and Part D revenue is tracked within separate accounts of the SMI Trust Fund.

The primary source of revenue for the HI Trust Fund is payroll taxes. Employers and employees each pay a 1.45 percent tax on workers’ earnings under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). Self-employed individuals pay the full 2.9 percent payroll tax on their net earnings under the Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA). While the Internal Revenue Service allows self-employed individuals to deduct the employer-equivalent portion of their SECA contributions for Federal income tax purposes, some self-employed individuals are effectively taxed higher than those who work for an employer, posing a financial barrier to entrepreneurship. Additionally, high-income workers pay an additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on their earnings above $200,000 (for individual filers) and $250,000 (for joint filers) under a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In 2024, the Federal government collected $396.4 billion in Medicare payroll taxes for the HI Trust Fund.

The next largest source of revenue for the HI Trust Fund is the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits above a certain threshold. Social Security beneficiaries with incomes above $34,000 (individual filers) or $44,000 (joint filers) pay income taxes on up to 85 percent of their benefits, with the additional revenues from the taxation of more than the first 50 percent going to the HI Trust Fund. Revenue from the taxation of Social Security benefits totaled $39.8 billion in 2024. The assets in the HI Trust Fund are invested in Treasury securities, which earn interest that is deposited in the Trust Fund, totaling $7.2 billion in 2024. Finally, the HI Trust Fund receives Medicare Part A premium revenue from enrollees who do not qualify for premium-free Part A, which represented $5 billion in revenue in 2024 (there are other miscellaneous revenue sources that provided $2.8 billion in 2024).

Figure 4: Payroll Tax Revenues vs. Medicare Part A Benefit Payments

For the SMI Trust Fund, the largest source of revenue is contributions from the Federal government. These transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury to the SMI Trust Fund totaled $497.6 billion in 2024, representing approximately 70 percent of program costs. The government contributions for the Part B program are based on a matching rate tied to premiums paid by Part B enrollees, with separate matching rates for enrollees who are aged 65 or older and those who have a disability. Part D government contributions are made on an as-needed basis to cover the portion of prescription drug expenditures that Medicare subsidies support. This constituted $111.6 billion in 2024 for Part D.

The next major source of SMI Trust Fund revenues is premiums from enrollees, $140.1 billion for Part B and $19.3 billion for Part D in 2024. States also make Part D payments for dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, which totaled $18 billion in 2024. As with the HI Trust Fund, the SMI Trust Fund earns interest on its assets invested in Treasury securities, representing $3.8 billion in 2024.

Current State of the Trust Funds

The HI Trust Fund and the SMI Trust Fund have different financing structures which impact how the Federal government considers the financial sustainability of each Trust Fund. The HI Trust Fund is meant to be self-financed through the dedicated funding source of payroll taxes, while the SMI Trust Fund relies on general tax revenues and beneficiary premiums. In its annual report to Congress, the Medicare Board of Trustees projects that the HI Trust Fund can only pay full scheduled Part A benefits until 2033 – three years earlier than the previous year’s projection – at which point Medicare will only be able to pay 89 percent of scheduled benefits when the reserves of the HI Trust Fund are depleted. For the SMI Trust Fund, the Medicare Board of Trustees projects full scheduled benefits will be payable indefinitely because government contributions and beneficiary premiums are adjusted annually to assist in covering expected program costs. However, the Medicare Board of Trustees remains concerned about the fast growth in Medicare Part B and Part D expenditures, which will put increasing pressure on the Federal government and beneficiaries to fund these rising costs through higher General Fund transfers and premiums, respectively.

Figure 5: Projected Depletion of HI Trust Fund in 2033

Medicare’s Impact

Measured by expenditures, Medicare is the largest health care insurance program in the United States and the second largest social insurance program behind Social Security. In 2024, Medicare spent over $1.1 trillion on health care benefits for 67.6 million enrollees in both Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans. Given the vital role of Medicare in supporting the health care of our nation’s elderly population, Medicare remains popular with the American public. A 2023 poll showed that 81 percent of respondents had a favorable view of Medicare, with comparable levels of favorability across political parties and age groups. Nevertheless, more than 80 percent of respondents were worried that Medicare will not be able to continue to provide at least the same level of benefits in the future that it provides to seniors today. As a result, 73 percent of respondents believed changes need to be made to keep Medicare financially sustainable for the future, though only 59 percent of those older than 65 held this belief (Medicare’s financial challenges and CED’s policy recommendations are discussed further below).

Medicare also plays a significant role in funding medical residency training, also known as graduate medical education (GME). Medicare is the largest Federal source of GME funding, paying an estimated $16.2 billion for GME in Fiscal Year 2020, primarily to hospitals. These GME payments cover both the direct costs of operating a residency program as well as indirect costs that may result in higher patient care costs in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals. As such, Medicare is a crucial funding source for residency slots and thereby the overall physician workforce in the United States.

Recent Challenges and Urgent Need for Reform

Medicare faces two main challenges related to long-term demographic trends and rising health care costs per beneficiary. The first challenge is an aging population, with members of the Baby Boom generation reaching Medicare eligibility in greater numbers. Combined with decreasing fertility rates and a proportionally smaller workforce to support payroll tax revenues, the number of workers per Medicare Part A beneficiary has declined dramatically over the past four decades, from approximately 4 workers per beneficiary in the period between 1980 and 2008 to 2.8 workers per beneficiary in 2024. The Medicare Board of Trustees projects this ratio to continue decreasing to 2.4 workers per beneficiary in 2034 before reaching only 2.2 workers per beneficiary in 2099. This disparity between Medicare beneficiaries and workers paying payroll taxes is a major reason for the short-term insolvency of the HI Trust Fund and its long-term negative actuarial balance (i.e., estimated income is insufficient to meet estimated HI Trust Fund obligations over the next 75 years).

Figure 6: Ratio of HI Workers per HI Covered Beneficiaries

The second financing challenge is rising health care costs per beneficiary. The United States already has the highest health care costs per capita compared to other advanced countries. The Medicare program is no exception – the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) projects Medicare Part A and Part B spending to grow by 4.5 percent annually after subtracting expected economy-wide inflation. This spending growth above and beyond inflation is primarily driven by the greater number of beneficiaries within the Medicare program and the volume and intensity of services used, particularly for Medicare Part B. Moreover, the number of older Americans over 80 is also expected to rise, from 25 percent of all seniors in 2020 to one-third of all seniors by 2060, sharply increasing the cost of care. MedPAC estimates spending per Medicare beneficiaries ages 85 and older was $17,600 in 2020 – driven by a greater number and complexity of health conditions that lead to higher ambulatory, inpatient, and prescription drug costs – compared to $10,100 for Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 to 74.

The US’s aging population and rising health care costs per beneficiary put pressure on the Federal budget, which is already running sustained, record-breaking deficits. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects Medicare spending to increase by 2 percent of GDP over the next 30 years, reaching 5.2 percent of GDP in 2055. Medicare will account for over two-thirds of Federal spending on major health care programs (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and premium tax credits for health insurance purchased through Affordable Care Act marketplaces) in 2055. To finance this increasing spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities.

Figure 7: Projected Medicare Spending as a Percentage of GDP