Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

For most Americans, Social Security is a key, if not the key, pillar of retirement income to provide economic security as they age. Social Security also provides crucial benefits to individuals with disabilities and the spouses and dependents of retired workers. Recent projections for the financial sustainability of Social Security continue to highlight both short-term and long-term challenges, primarily tied to demographic trends. In light of these challenges, Congress must act to consider a comprehensive package of legislative changes to redirect the financial trajectory of the program to preserve Social Security benefits for the millions of Americans that depend on them.

As background for that work, this Explainer provides a history of the establishment of Social Security and subsequent reforms; an overview of the two Social Security Trust Funds, eligibility for retirement benefits, payroll taxes that fund Social Security, and Social Security Disability Insurance; the impact of Social Security; and recent challenges to the solvency of the Trust Funds along with recommendations to improve the fiscal picture for the program and save it for future generations of Americans.

- Approximately 69.8 million Americans receive monthly Social Security benefits, and the Social Security program provides a vital source of income for retired workers, individuals with disabilities, survivors, and their families.

- Congress established Social Security in 1935 as a response to the economic insecurity elder Americans experienced during the Great Depression. The program was subsequently expanded to cover additional workers and provide benefits to spouses, dependents, survivors, and individuals with disabilities.

- Social Security has two Trust Funds – the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund – that receive revenues from payroll taxes on employees and their employers, Federal income taxes on a portion of Social Security benefits, and interest income from investing reserves in Treasury securities.

- Social Security retirement benefits are calculated based on when a worker decides to begin collecting benefits using a worker’s historical earnings. The monthly benefit amounts are also adjusted annually to account for cost-of-living increases.

- Current projections from the Social Security Trustees show that the OASI Trust Fund for retirement benefits is scheduled to be depleted in 2033, meaning that scheduled benefits will be reduced by 23 percent absent legislative changes. Long-term projections also show that total program costs will exceed total program revenues over the 75-year forecast period.

- The long-term demographic trends of increases in life expectancy and declining birth rates and immigration have contributed to this fiscal imbalance, as retirees collect benefits for longer and there are fewer covered workers per beneficiary paying payroll taxes.

- Congress must summon the political will to negotiate solutions and promptly phase them in to return the program to sound financial footing, give future retirees sufficient time to adjust their financial planning, and preserve benefits for current and future generations.

Introduction

Before the establishment of Social Security, there was no comprehensive, national program to promote economic security in the face of unemployment, illness, disability, and old age. The first relatively widespread program in the United States was the Civil War Pension program for former Union soldiers and their survivors, a significant expenditure for the Federal government in the 1890s accounting for 37 percent of the entire Federal budget in 1894. Around this time, private businesses began instituting company pension plans for their workers, though only about 15 percent of workers had access to these pension plans by the early 1930s.

The period of the late 19th century and early 20th century was defined by the Industrial Revolution, the urbanization of the United States, the decline in the inclusion of the elderly as part of the family household, and significant increases in life expectancy, all of which led to a population that was older and more urban with less access to traditional sources of economic security such as assistance from families. After the financial crash of 1929, during the Great Depression, the US experienced massive unemployment, widespread business failures, and the loss of personal savings, leaving millions destitute. The economic effects fell particularly harshly on the elderly, with one-third to one-half of the elderly dependent on family or friends for economic support.

In response to the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression, various social movements emerged demanding radical reforms to the economic system, including the establishment of old-age pensions for all citizens. Recognizing the need for action, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Committee on Economic Security in 1934, led by Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, to study the problem of economic insecurity and make recommendations for legislation in Congress. The result of these efforts was the Social Security Act of 1935 that established a federally administered system of social insurance for the elderly financed by payroll taxes from employees and their employers. The program now known as Social Security, originally intended as a safety net to supplement lifetime savings, has been expanded over the decades to encompass retirement benefits, disability benefits, and payments to the families of beneficiaries.

Overview of Trust Funds

Social Security consists of two parts:

- The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program provides monthly payments to retired workers, their families, and survivors of deceased workers. As of June 2025, the OASI program paid out $118.1 billion in total monthly benefits to 61.6 million beneficiaries, for an average monthly benefit of $1,916.

- The Disability Insurance (DI) program provides monthly payments to disabled workers and their families. As of June 2025, the DI program paid out $11.8 billion in total monthly benefits to 8.2 million beneficiaries, for an average monthly benefit of $1,443.

Most often, references to “Social Security” are to the OASI program, but the DI program is important as well. Each program has a dedicated Trust Fund from which benefits are paid out. The Trust Funds receive income from payroll tax contributions made by covered employers and employees and from the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits that are subject to the Federal income tax. Employees and employers each pay 5.3 percent in payroll taxes for OASI and 0.9 percent in payroll taxes for DI on earnings up to a fixed amount set annually.

The Department of the Treasury is legally required to invest all Trust Fund income in interest-bearing securities issued by the Federal government, so the Trust Funds also earn interest income from these investments, which accounted for $69 billion of program revenues in 2024. As of 2024, Social Security has collected approximately $29.2 trillion and paid out $26.5 trillion in monthly benefits over the course of the entire program’s history, leaving the Trust Funds with a reserve of approximately $2.7 trillion.

Overview of the Social Security Program

The Social Security Administration (SSA) administers Social Security benefits, including issuing Social Security numbers, tracking eligibility, and calculating benefits. SSA also administers the separate Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program that provides monthly benefits to individuals with limited income and resources who are disabled, blind, or age 65 or older. In addition, the Social Security program has a Board of Trustees that oversees the financial operations of the OASI and DI Trust Funds. The Board of Trustees is composed of six members: the Secretaries of the Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services, the Commissioner of Social Security, and two public representatives appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

Social Security Retirement Benefits

Eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits is tied to “credits” workers earn when they pay Social Security taxes or the self-employment tax. In 2025, workers earn one credit for each $1,810 in earnings, up to a maximum of four credits per year. To be eligible for retirement benefits, workers need 40 credits, or the equivalent of ten years of work.

Family members of retired workers are also eligible to receive Social Security retirement benefits. Spouses can receive benefits if they are age 62 or older or if they are caring for the retired worker’s child. Unmarried children of retired workers can also be paid benefits if they are under 18 years old, a full-time student under 19 years of age, or have a qualifying disability. Under certain circumstances, divorced ex-spouses may be eligible for benefits based on the retired workers’ earnings. Social Security also pays survivor benefits after a retired worker dies to their surviving spouse, unmarried children, and divorced ex-spouses if eligible, usually amounting to 75 to 100 percent of the deceased retiree’s basic retirement benefits. Additionally, there is a total maximum family benefit between 150 to 188 percent of a worker’s benefits.

After an individual completes at least 40 credits of work and becomes eligible for Social Security retirement benefits, the worker may choose among three retirement ages (for the first two, in essence, the date a worker chooses to begin accepting Social Security benefits if otherwise eligible) that determine the amount of benefits the worker can receive:

- The full retirement age is 66 years for individuals born before 1955, between 66 and 67 years of age for workers born between 1955 and 1959, and 67 years of age for workers born in 1960 or later. Choosing to retire at this age means the worker will receive their full benefit amount.

- Workers may choose to retire earlier than their full retirement age and begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits as early as age 62, known as the early retirement age. However, in most cases, SSA permanently reduces benefits by roughly 0.5 percentage points on average for each month a worker chooses to retire before their full retirement age. As an example, a worker with a full retirement age of 67 who chooses to retire at 62 would only receive approximately 70 percent of the Social Security retirement benefit available from retiring at the full retirement age.

- Further, if a worker begins collecting Social Security retirement benefits before their full retirement age and continues working, the worker is subject to the retirement earnings test. For workers attaining their full retirement age after 2025, SSA will withhold $1 in benefits for every $2 of earnings above $23,400. For workers attaining their full retirement age in 2025, SSA will withhold $1 in benefits for every $3 of earnings above $62,160 (only for earnings made in the months prior to the month of full retirement age attainment). Crucially, the worker does not lose these withheld benefits – instead, monthly benefits after the full retirement age are permanently increased to account for the withholdings prior to a worker’s full retirement age, with the beneficiary recouping most or all of the withheld benefits over a typical life span.

- Conversely, workers may delay collecting Social Security retirement benefits after their full retirement age up to age 70, known as the delayed retirement age. For every year after the full retirement age that the worker chooses to delay collecting benefits, SSA will apply a credit and permanently increase the full retirement benefit amount by eight (8) percentage points. To continue the example above, a worker with a full retirement age of 67 who chooses to delay collecting benefits until age 70 will receive approximately 124 percent of their full Social Security retirement benefit.

The goal of these actuarial adjustments to benefits according to retirement age is to provide the worker with roughly the same amount of total lifetime benefits based on average life expectancy.

A worker’s full Social Security benefit amount is known as the primary insurance amount (PIA) and is calculated based on a worker’s historical earnings. SSA first adjusts a worker’s earnings based on the national average wage index to reflect changes in general wage levels that occurred during the worker’s years of employment. SSA then selects the 35 years with the highest indexed earnings, sums the adjusted earnings, and divides the total adjusted earnings by the total number of months in the selected years. The result of this calculation is called the average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). It’s important to note that for workers with fewer than 35 years of earnings in covered employment, years with no earnings count as zeroes in the AIME calculation, so these workers will have a lower AIME and therefore a lower PIA than they would if they had worked 35 years.

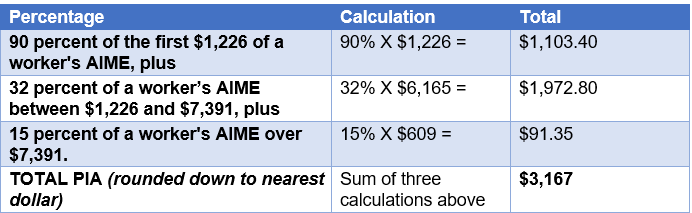

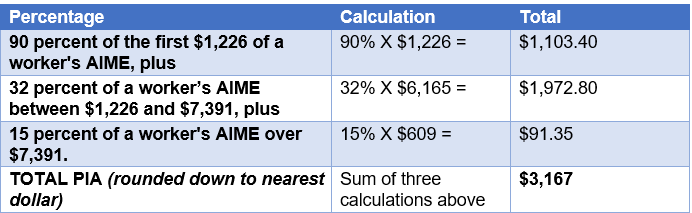

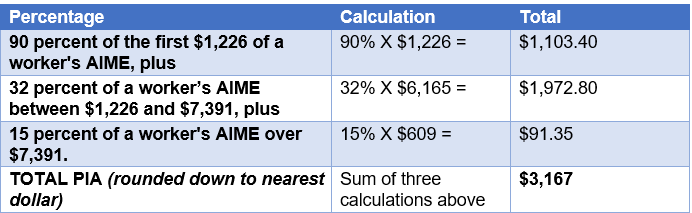

To calculate a worker’s PIA, SSA uses the following formula based on three separate percentages of a worker’s AIME, known as “bend points”:

- 90 percent of the first $1,226 of a worker's AIME, plus

- 32 percent of a worker’s AIME between $1,226 and $7,391, plus

- 15 percent of a worker's AIME over $7,391.

The bend point values of $1,226 and $7,391 are for 2025 and are also adjusted annually according to the national average wage index. The table below presents an illustrative example of a worker’s PIA at eligibility based on an AIME of $8,000.

Table 1: Illustrative Example of PIA Calculation for Eligible Worker with AIME of $8,000 in 2025

Finally, before 2025, SSA adjusted an individual’s monthly Social Security benefit if they also received a retirement or disability pension from certain government work not covered by Social Security. These pensions included the Federal civil service, some state or local government employment, or work in a foreign country for which the worker did not pay US Social Security payroll tax. If an individual didn’t pay Social Security payroll taxes on their government or foreign employment earnings, SSA reduced their monthly retirement benefit according to two rules, the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and Government Pension Offset (GPO). The Social Security Fairness Act, enacted in January 2025, eliminated WEP and GPO, increasing Social Security benefits for affected workers.

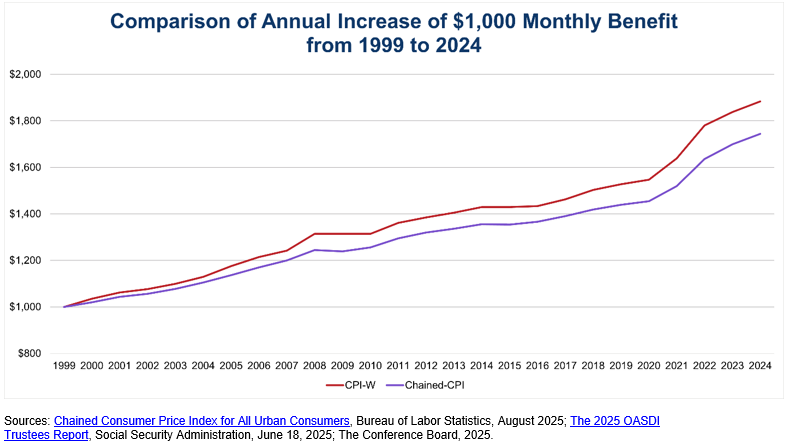

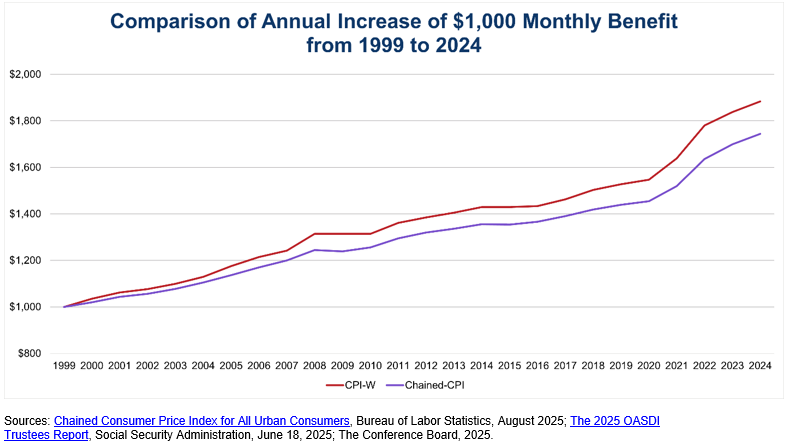

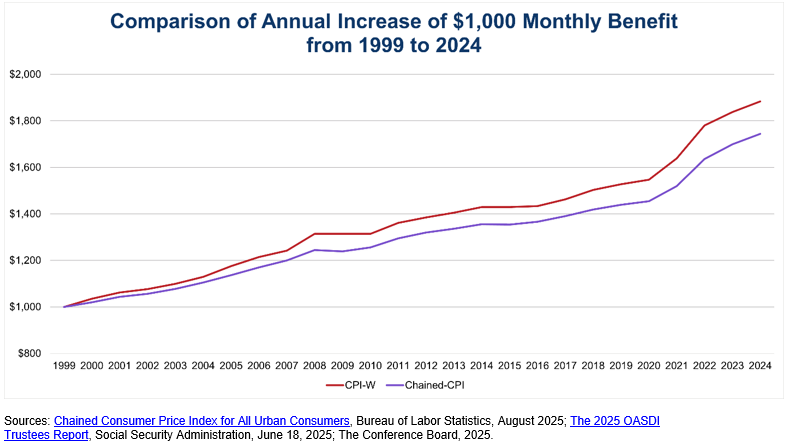

Once an eligible worker starts collecting Social Security retirement benefits, those benefits are adjusted annually for inflation, known as a Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA), based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which is determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also produces another cost-of-living measure called the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (chained-CPI) that accounts for consumer substitution among item categories in response to changes in relative prices. As discussed in the section on recent challenges below, using chained-CPI as opposed to CPI-W is an option to improve the solvency of the Social Security Trust Funds and bolster the sustainability of the program for future generations.

Figure 1: Comparison of Using CPI-W vs. Chained-CPI for Social Security COLAs

Payroll Taxes and Other Revenue for Social Security

Social Security’s main source of revenue is the payroll tax on employees (including self-employment) and their employers. An estimated 93 percent of workers in paid employment and self-employment are covered under Social Security and must pay these payroll taxes. Under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA), employees and employers each pay 6.2 percent in payroll taxes (5.3 percent for OASI and 0.9 for DI) on earnings up to a fixed amount set annually ($176,100 in 2025), which employers remit to the US Treasury on a regular basis. Under the Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA), self-employed individuals must pay the full 12.4 percent in Social Security payroll taxes on earnings up to the fixed amount ($176,100 in 2025). While the Internal Revenue Service allows self-employed individuals to deduct the employer-equivalent portion of their SECA contributions for Federal income tax purposes, self-employed individuals are effectively taxed higher than those who work for an employer, posing a financial barrier to entrepreneurship.

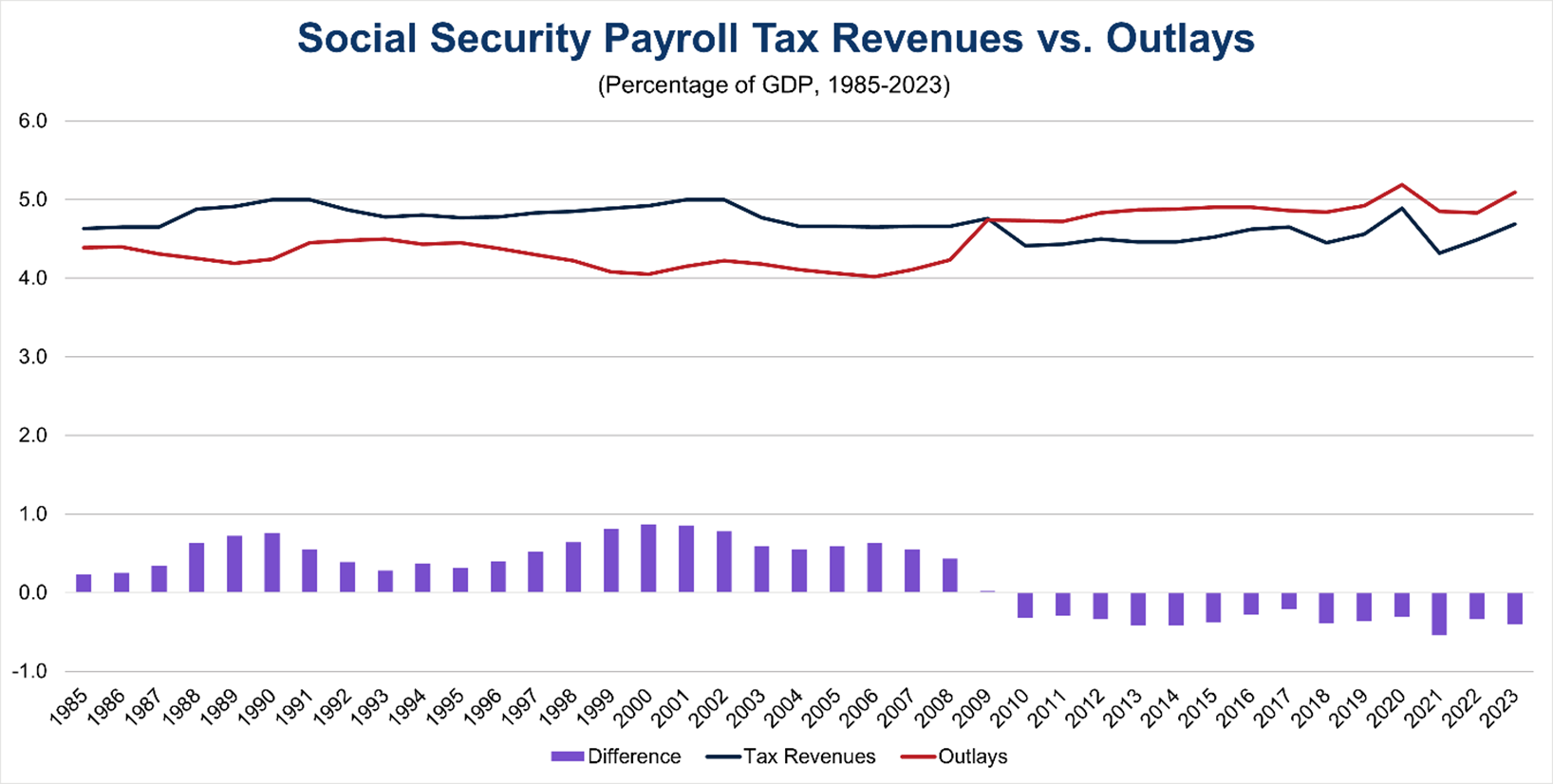

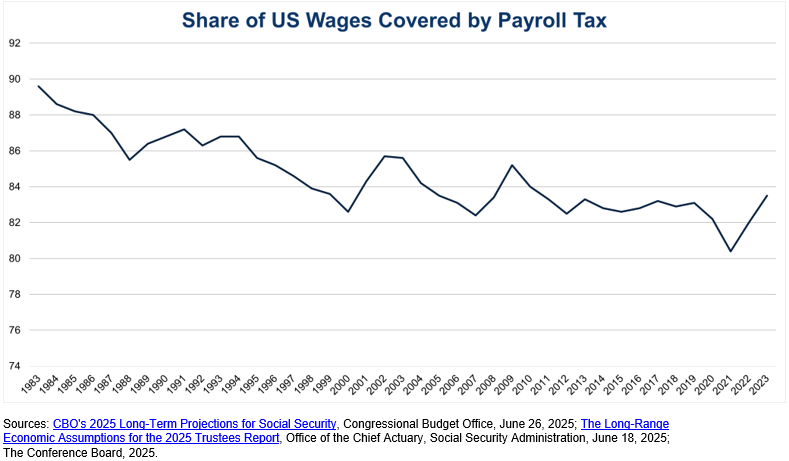

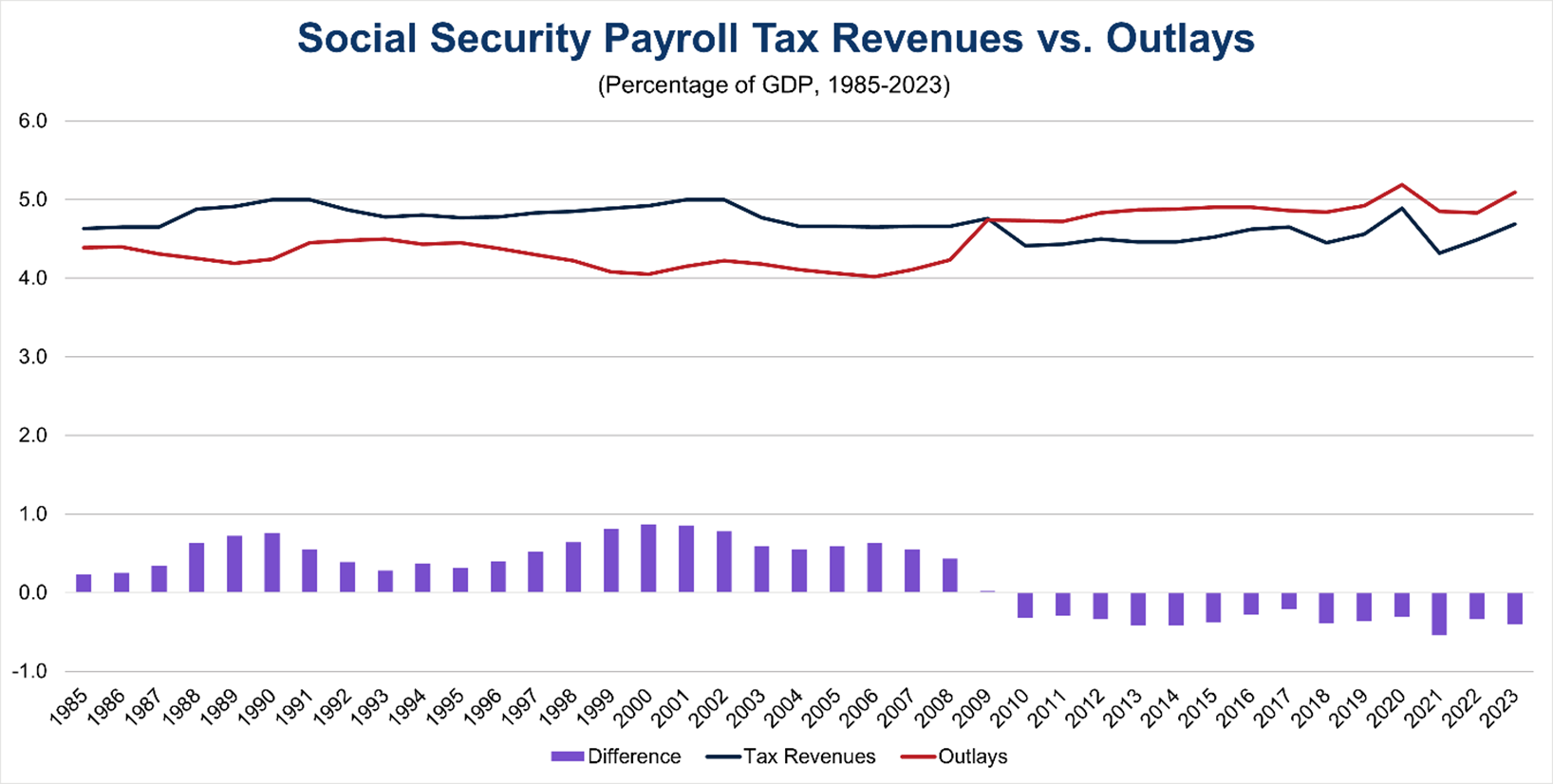

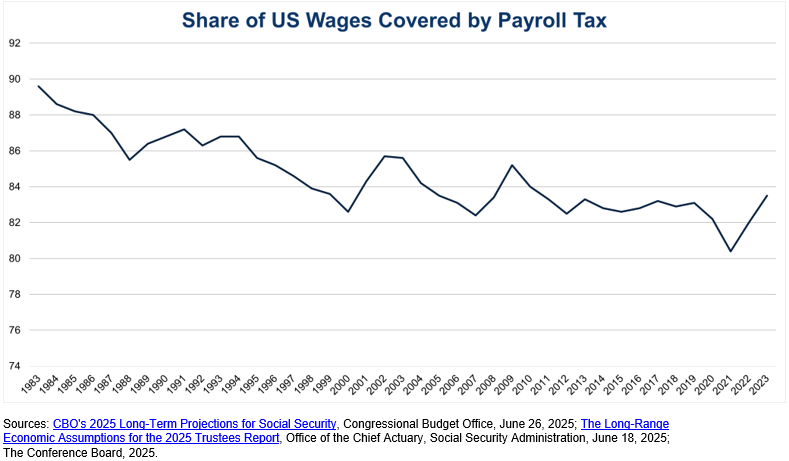

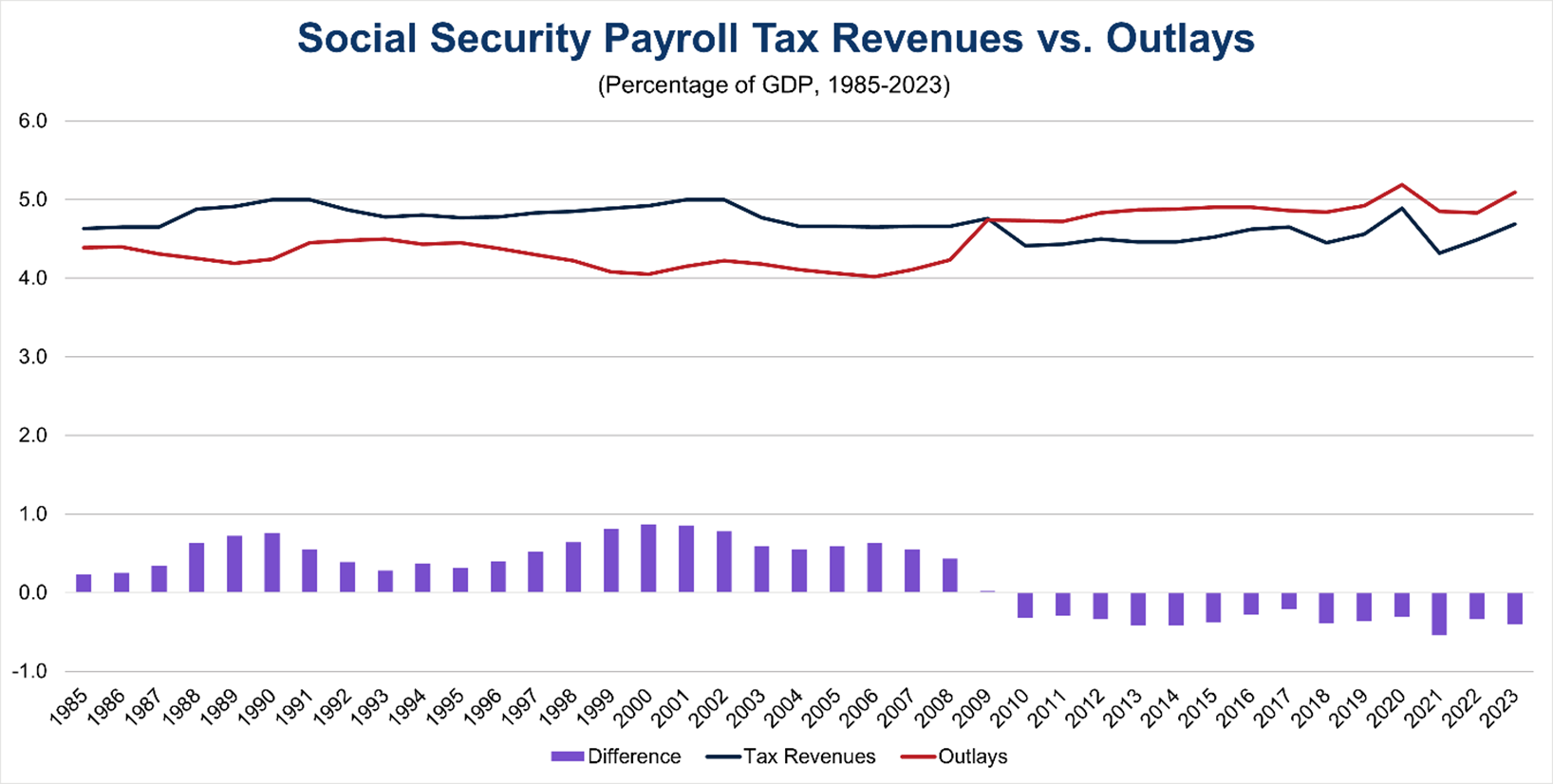

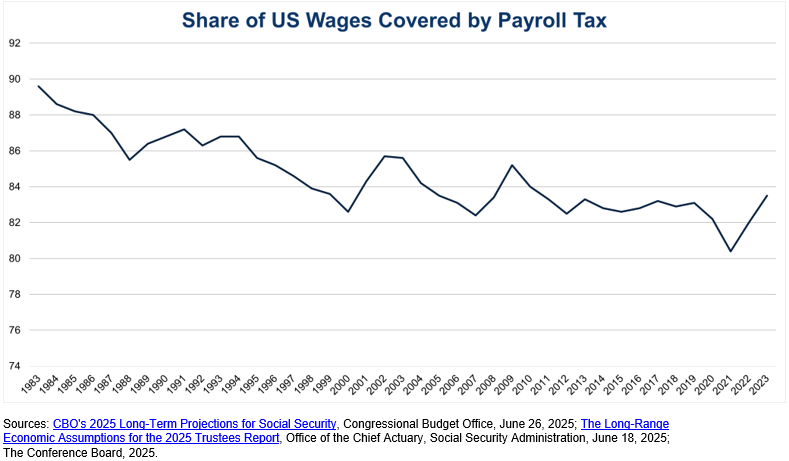

Figures 2 and 3: Payroll Tax Revenues and Share of US Wages Covered by the Payroll Tax

In 2024, the OASI Trust Fund received net payroll tax contributions of $1,105.6 billion and the DI Trust Fund received net payroll tax contributions of $187.7 billion. An important trend in payroll tax revenues has been the decline in total wages covered under the payroll tax. The ratio of taxable payroll to covered earnings declined from 88.6 percent in 1984 to 82.6 percent in 2020, primarily due to significant increases in income for very high earners as opposed to all other earners. In effect, the growth in earnings at the very top of the income scale has vastly outpaced the growth in the maximum income subject to the payroll tax, causing this drop in the ratio. The ratio has fluctuated over the past 20 years in connection with business cycle changes, settling to an estimated ratio of 83.3 percent in 2023.

In addition, Social Security receives revenue from the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits above a certain threshold. Up to 50 percent of an individual’s Social Security benefits are subject to the Federal income tax if an individual filer reports more than $25,000 in total income or if a joint filer reports more than $32,000 in total income. In 2023, approximately 50 percent of Social Security beneficiaries reported income that exceeded these thresholds and paid Federal income tax on a portion of their benefits, resulting in revenue of $55.1 billion across both the OASI and DI Trust Funds in 2024.

Finally, Social Security receives revenue from the interest the Trust Funds collected by investing in US Treasury securities. In 2024, the combined Trust Fund reserves earned interest at an effective annual rate of 2.5 percent, resulting in interest income of $69.1 billion across both the OASI and DI Trust Funds.

Transfers from the General Fund

Social Security has received transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury in the past as a temporary measure to plug short-term financing issues. For example, Congress enacted a temporary payroll tax cut in 2011 and 2012 to stimulate the economy after the 2008 financial crisis and approved General Fund transfers to reimburse Social Security for the lost revenue. Despite this precedent, using General Fund revenues to finance Social Security in the long term is not a prudent option because the Federal government is already running massive fiscal deficits, which would lead to the issuance of additional Treasury securities at higher interest rates to finance these transfers and an increase in the cost of servicing the debt.

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

As mentioned above, Social Security also provides benefits to individuals who have developed a disability or are blind and have made contributions to the Social Security Trust Funds through payroll taxes. These monthly benefits are known as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and are calculated based on lifetime average earnings covered by Social Security. Individuals must meet Social Security’s disability criteria and may have their benefits reduced if they receive Workers’ Compensation payments and/or other public disability benefits. SSA periodically reviews SSDI cases to assess whether an individual’s condition has medically improved or if that individual can perform substantial gainful activity. SSA provides a variety of work incentives and employment supports to assist individuals on SSDI to return to work or continue working without risking a sudden loss of benefits. Individuals are also entitled to Medicare health benefits if they have received SSDI for 24 months.

Impact of Social Security

Social Security benefits are the largest single source of income among Americans aged 65 and older. For 4 in 10 retirees, Social Security provides at least 50 percent of their income, and for 1 in 7, it provides at least 90 percent. In 2021, 10 percent of adults aged 65 or older had income below the poverty line. Without Social Security, nearly four times as many older Americans (22.4 million) would fall below that line. Thus, Social Security is a key pillar of economic security for older Americans.

Social Security is also extremely popular. In a 2020 AARP survey, 96 percent of those polled regardless of party affiliation said Social Security was either the most important government program or an important one compared with other government programs. More recent YouGov polling from 2023 shows that Social Security had the highest net favorability rating among eight entitlement programs in the United States and that 76 percent of Americans had a favorable view of the program, with these opinions holding regardless of party affiliation.

Current State of the Trust Funds

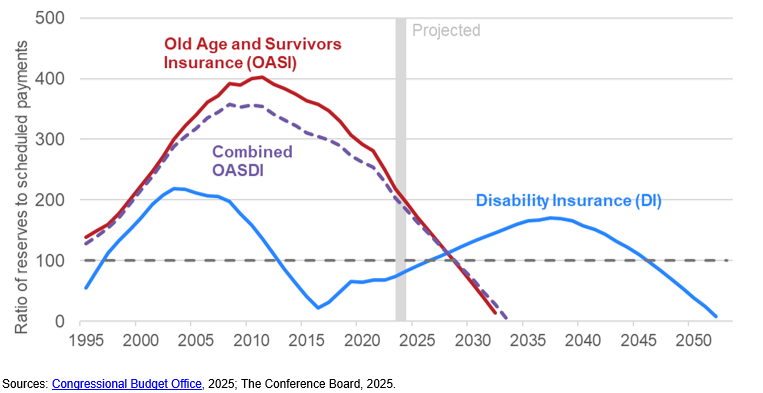

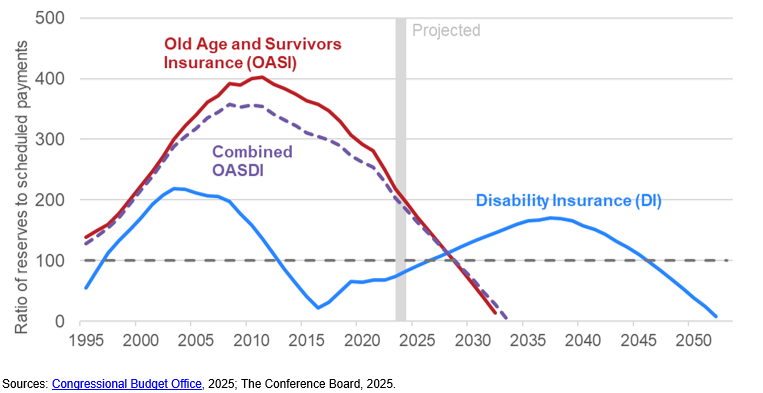

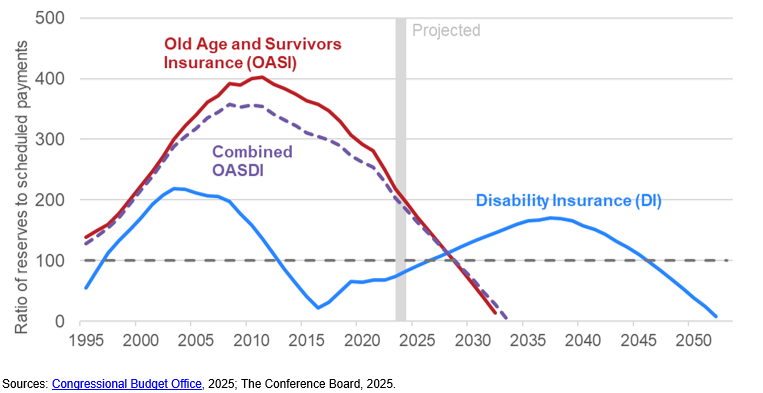

Since 2010, Social Security has operated under cash-flow deficits, meaning that the amount of monthly benefits paid out has exceeded the amount of tax revenues collected each year. Congress has not acted to change the program since then because lawmakers anticipated that a recovering economy and ample reserves would cover the annual revenue shortfalls. Starting in 2021, total costs for Social Security have exceeded total income (inclusive of payroll taxes, Federal income taxes, and interest income), leading to a net decrease in the reserves for the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds. The Social Security Board of Trustees predicts this trend to continue through the remainder of its 75-year projection period, leading to the depletion of the OASI Trust Fund by 2033. The Congressional Budget Office also predicts the depletion of the OASI Trust Fund by 2033.

Figure 4: Social Security’s Primary OASI Trust Fund Is Projected to Be Depleted by 2033 (Social Security Trust Fund Ratios)

The depletion of the OASI Trust Fund reserve and the fact that scheduled benefits are projected to exceed tax revenues means that Social Security will not have the ability to pay Social Security retirement benefits in full and on time starting in 2034, absent legislative changes. Under current law, SSA is not permitted to transfer funds between the DI Trust Fund and OASI Trust Fund and cannot borrow from the general fund of the Treasury to cover the gap between revenues and scheduled benefits. Thus, on current estimates, Social Security can only pay 77 percent of scheduled OASI retirement benefits in 2034 -- falling from 79 percent last year. A more detailed discussion of the causes of this imbalance and potential options for saving Social Security is presented below.

History of Social Security Reforms

At times, the Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in the history of Social Security. In the mid-1930s, the Supreme Court invalidated major pieces of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, leading the President to advocate for additional powers to appoint new Federal judges, including six new Justices to the Supreme Court. While the President’s proposal was resoundingly rejected by Congress, the nine Justices on the Supreme Court began ruling differently on the constitutionality of New Deal programs. When the constitutionality of the payroll tax was challenged in Helvering v. Davis (1937), the Supreme Court ruled 7 to 2 in support of the OASI program. In 1960, the Supreme Court ruled in Flemming v. Nestor that Social Security is a non-contractual government benefit, meaning that an individual is not automatically entitled to Social Security even if they have paid payroll taxes. The Supreme Court has also granted Social Security eligibility to additional groups, including to widowers in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975). Finally, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Lee (1982) that employers cannot claim a religious exemption under the First Amendment to paying Social Security taxes on behalf of their employees.

After the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935, Congress enacted several reforms over the next fifty years, primarily to expand the program and improve the sustainability of its finances. The first major amendments to Social Security were enacted in 1939 to expand the program to provide benefits to dependents of retired workers (spouses and minor children) and survivors. The 1939 reforms also changed the calculation of benefits to be based on average monthly earnings instead of cumulative wages and reduced the size of required Trust Fund reserves to move the program toward “pay-as-you-go” financing. The Federal government began mailing monthly benefit checks in 1940.

After World War II, inflation reduced the purchasing power of Social Security retirement benefits, and there was a growing recognition of the economic insecurity workers faced from disability (including those who had become disabled in World War II). In response, Congress enacted the first COLA for Social Security benefits in 1950 that provided across-the-board benefit increases and a 77 percent increase to the minimum benefit. Subsequent amendments to the Social Security Act in 1954 and 1956 expanded the number of workers covered under Social Security, leading to approximately 90 percent of workers covered by the mid-1950s. These amendments also instituted a “disability freeze” of a worker’s Social Security record during years of disability to prevent a reduction of benefits for these workers and a new disability benefit for workers aged 50 to 64 and for disabled adult children who had a disability that began before the age of 18 and were survivors or dependents of Social Security beneficiaries. In 1958 and 1960, Congress enacted another series of amendments to expand benefits to disabled workers of any age and their spouses and dependents. Social Security’s finances were relatively strong during this period and into the mid-1970s. OASI Trust Fund asset reserves grew or only declined by less than 10 percent throughout the period. The ratio of OASI asset reserves to program costs was also approximately 100 or above until 1970, meaning that the reserves in the OASI Trust Fund could fully cover at least one year of Social Security program costs.

The next significant amendment to Social Security was in 1972 to establish automatic COLAs in response to the strong inflation of the period. However, the calculation of COLAs for benefits was coupled with an adjustment to account for wage increases that resulted in immediate financing challenges for the program when combined with the negative economic conditions of the 1970s. Congress passed another set of amendments in 1977 to address the financing of Social Security by gradually raising the payroll tax to its current levels, increasing the wage base, reducing benefits slightly, enacting the GPO rule, and decoupling wage adjustments from benefit COLAs.

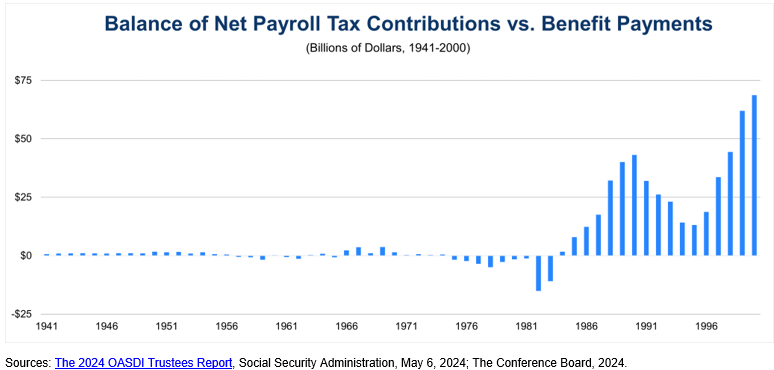

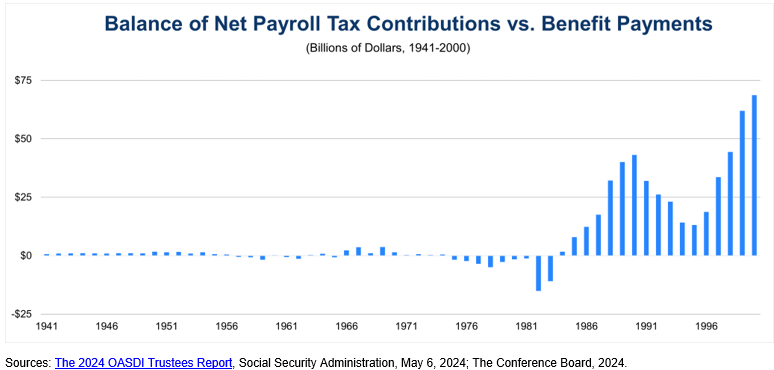

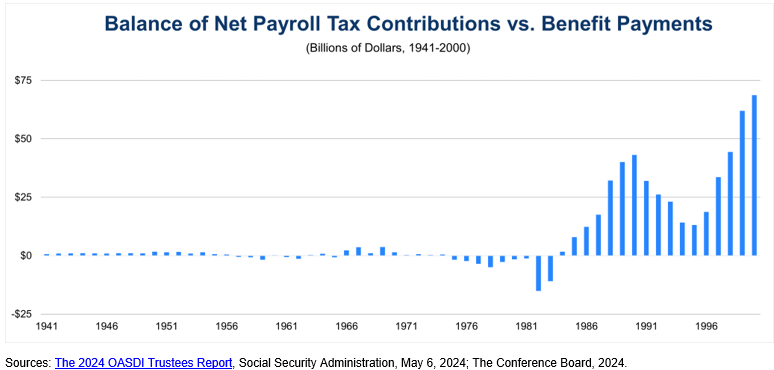

Figure 5: Benefit Payments Exceeding Payroll Tax Revenues Has Historically Preceded Reforms

Despite these reforms, Social Security faced both a short-term financing crisis and a long-term solvency issue in the early 1980s, primarily due to high inflation, significant unemployment, and stagnant wages. The combined balances of the OASDI Trust Funds peaked at $45.9 billion in 1974 before declining precipitously to $16.9 billion by the end of October 1982. The balance in the OASI Trust Fund for retirement benefits was so low in the Fall of 1982 that the OASI Trust Fund was forced to borrow from the DI Trust Fund and Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund to fully pay scheduled benefits. Long-term demographic projections also revealed that increases in life expectancy and declines in birth rates would further strain the program’s finances in the future.

To address the financing crisis, President Reagan appointed the National Commission on Social Security Reform led by Alan Greenspan to study the issue and recommend reforms to Congress. The Greenspan Commission was established due to “the continuing deterioration of the financial position of the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, the inability of the President and the Congress to agree to a solution, and the concern about eroding public confidence in the Social Security system.” The Commission consisted of 15 members appointed on a bipartisan basis, with five selected by each of the President, the Senate Majority Leader, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The resulting legislation, the Social Security Amendments of 1983, represented the last major reform of the program to date. These amendments gradually raised the full retirement age to 67 over a period of 40 years, accelerated the payroll tax increases enacted in 1977, permanently increased self-employment payroll tax rates, made half of Social Security benefits taxable under the Federal income tax for certain high-income beneficiaries, and enacted the WEP rule (now repealed in the Social Security Fairness Act in 2025).

Reforms after 1983 focused largely on work requirements and work incentives for beneficiaries receiving SSDI and SSI benefits. In 2000, Congress repealed the retirement earnings test for beneficiaries at or above the full retirement age. President George W. Bush made Social Security reform a top priority of his Administration, even appointing a commission in 2001 to study the issue and make recommendations. However, Congress did not enact any major changes to Social Security after 2000.

Recent Challenges and Urgent Need for Legislative Action

As in the early 1980s, Social Security today faces challenges to both its short-term financing and long-term solvency due to demographic trends. Life expectancy at birth has increased dramatically in the United States since 1940, going from 61.4 years for men and 65.7 years for women to 76.6 years for men and 81.5 years for women in 2024. Given these increases are closely tied to declining infant mortality, a better measure is life expectancy at age 65, which is near the full retirement age for Social Security. In 1940, men could be expected to live an additional 11.9 years at 65 and women could be expected to live an additional 13.4 years at 65. In 2024, men could be expected to live an additional 18.3 years at 65 and women an additional 20.9 years at 65. These increases in life expectancy mean that Social Security is paying out benefits longer to retired workers.

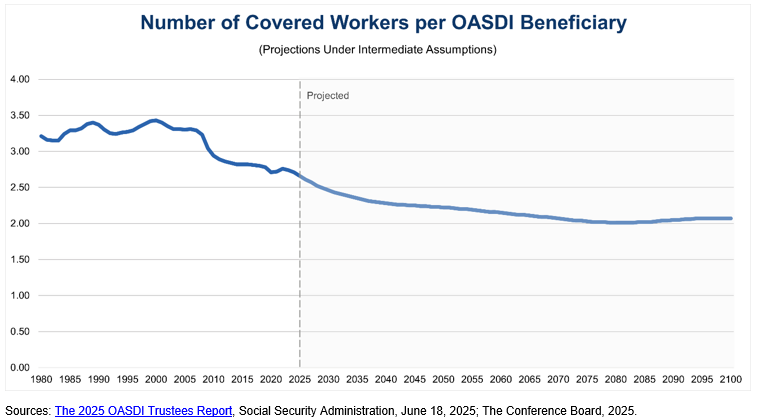

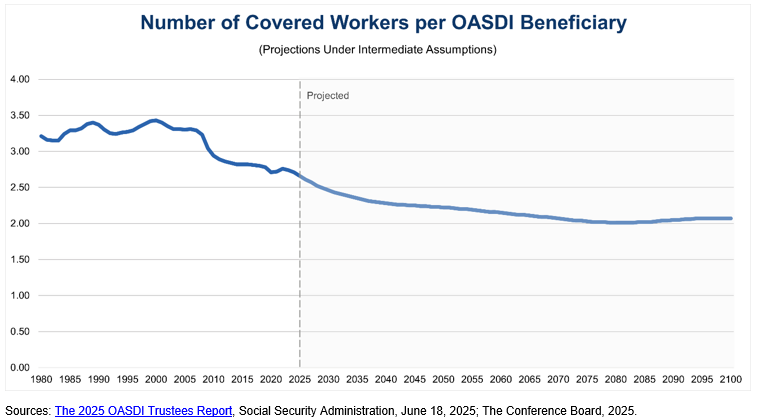

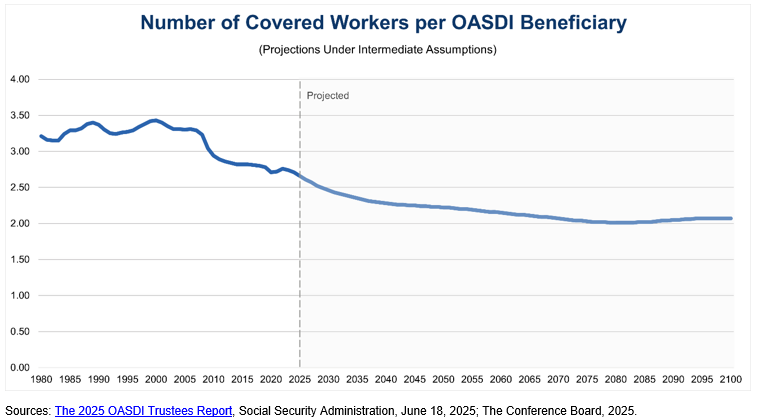

Over the same period, the total fertility rate has decreased, meaning women are giving birth to fewer children. In 1940, the total fertility rate, or the average number of children born to a woman, was 2.23, increasing to 3.61 by 1960 due to the Baby Boom generation. Since then, the total fertility rate has declined to 1.62 in 2024. This decline in population growth has caused the ratio of covered workers per OASDI beneficiary to decrease concomitantly, as shown below. In 1960, this ratio was 5.1 covered workers per beneficiary; in 2024, this ratio has decreased to 2.7 covered workers per beneficiary. As such, there are fewer workers paying into Social Security for every beneficiary receiving monthly payments. (Increased legal immigration could make up for the difference from declining fertility rates, increasing the ratio of covered workers per beneficiary.)

Figure 6: Covered Workers per OASDI Beneficiary (Historical and Projected)

These two trends combine to cause a deteriorating financial picture for Social Security, as both the Social Security Board of Trustees and CBO predict the OASI Trust Fund will be depleted by 2033 absent legislative action. The Trustees also predict total costs to exceed total revenues throughout their 75-year projection period. The American public’s confidence in the solvency of Social Security reflects these worrisome trends. In Gallup polling from 2023, 47 percent of non-retirees believe the Social Security system will not be able to pay them a benefit when they retire and 43 percent of retirees believe there will eventually be cuts in their benefits. Respondents also worried a “great deal” (45 percent) or a “fair amount” (29 percent) about the Social Security system.

Social Security is also an important component of the Federal budget and US GDP, and the program’s finances therefore have significant effects on the national debt and the American economy. Some advocates and commentators have argued that Social Security should not be considered as contributing to the deficit because by law, Social Security can only pay benefits from its Trust Funds. Once the Trust Fund reserves are depleted, Social Security is currently limited to paying benefits that are covered by incoming revenues (payroll taxes and income taxes on a portion of Social Security benefits). Nevertheless, this perspective ignores the size of Social Security in relation to overall Federal outlays and receipts and overall GDP. In 2025, estimated revenues to Social Security are 4.7 percent of GDP and comprise more than 27 percent of Federal receipts. Social Security outlays are also estimated to be 5.3 percent of GDP in 2025 and 23 percent of total Federal outlays, according to CBO’s latest estimates.

Because of this impact on the economy, both the President’s annual Budget and CBO adopt a “unified budget framework” that includes Social Security to provide a more comprehensive picture of the size of the Federal government and the budget’s impact on the economy. This unified framework is also how investors in Treasury securities assess the ability of the US government to fulfill its obligations and repay its debts. Social Security is an entitlement and commitment from the Federal government to retirees and other eligible beneficiaries. As the costs of servicing the national debt increase, investors in the market will take a comprehensive view of the Federal government’s financial position when making their decisions on buying and selling US Treasury securities, thereby affecting market interest rates and the broader economy.

Given the financial challenges facing Social Security, Congress must urgently act to address the financial imbalances, both in the short-term and the long-term. SSA, CBO, and other organizations like the American Academy of Actuaries have released options for saving Social Security, which CED has summarized in its Solutions Brief on Social Security. These options can be grouped into three categories:

- Benefit adjustments: These options would reduce the costs of the Social Security program to ensure that future generations of retirees can still collect close to the full scheduled benefits. Benefit adjustments include gradually raising the full retirement age to 69 and the delayed retirement age to 72 while continuing to allow for early retirement at 62, implementing modest means testing for high-income beneficiaries, using chained-CPI instead of CPI-W for COLAs, and removing work disincentives for retirees.

- Revenue raisers: These options would bolster the income that the Social Security Trust Funds receive to restore a positive cash flow and rebuild Trust Fund reserves. Payroll taxes could be gradually increased to bring in additional revenue, though these taxes are regressive for low-income workers and disproportionately impact self-employed individuals that drive American entrepreneurship. The maximum taxable earnings of $176,100 for the payroll tax could be increased or eliminated to restore total payroll tax revenues to a higher percentage (for instance, 90 percent) of total US income, as it was in 1983 at the time of the last major reforms. Newly hired state and local workers could also be covered under Social Security to cover more wages under the payroll tax.

- Diversifying Trust Fund investments: Currently, reserves in the Trust Funds must be invested in US Treasury securities, which typically have lower returns than other investments such as index funds that track the major stock market indices. Changing the law to allow for investments beyond Treasury securities could increase the interest income the Trust Funds make and bolster revenues while also raising significant questions about how these funds would be managed.

Apart from a sizeable increase in the payroll tax, none of these options by themselves fully addresses the short-term and long-term challenges facing Social Security. As such, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress must also protect vulnerable populations of retirees by increasing the minimum benefit to protect low-wage workers and those with intermittent careers and by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide Americans approaching retirement with sufficient time to adjust their retirement planning.

Conclusion

Social Security is a vital and immensely popular program that supports retired workers, their families, and individuals with disabilities. Given the impending depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund that supports retirement benefits over the next decade, it is crucial that Congress addresses this issue quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to Social Security. The longer the delays, the greater the chances that the necessary legislative changes to save Social Security will be disruptive to beneficiaries and the broader economy.

For further reading

Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

For most Americans, Social Security is a key, if not the key, pillar of retirement income to provide economic security as they age. Social Security also provides crucial benefits to individuals with disabilities and the spouses and dependents of retired workers. Recent projections for the financial sustainability of Social Security continue to highlight both short-term and long-term challenges, primarily tied to demographic trends. In light of these challenges, Congress must act to consider a comprehensive package of legislative changes to redirect the financial trajectory of the program to preserve Social Security benefits for the millions of Americans that depend on them.

As background for that work, this Explainer provides a history of the establishment of Social Security and subsequent reforms; an overview of the two Social Security Trust Funds, eligibility for retirement benefits, payroll taxes that fund Social Security, and Social Security Disability Insurance; the impact of Social Security; and recent challenges to the solvency of the Trust Funds along with recommendations to improve the fiscal picture for the program and save it for future generations of Americans.

- Approximately 69.8 million Americans receive monthly Social Security benefits, and the Social Security program provides a vital source of income for retired workers, individuals with disabilities, survivors, and their families.

- Congress established Social Security in 1935 as a response to the economic insecurity elder Americans experienced during the Great Depression. The program was subsequently expanded to cover additional workers and provide benefits to spouses, dependents, survivors, and individuals with disabilities.

- Social Security has two Trust Funds – the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund – that receive revenues from payroll taxes on employees and their employers, Federal income taxes on a portion of Social Security benefits, and interest income from investing reserves in Treasury securities.

- Social Security retirement benefits are calculated based on when a worker decides to begin collecting benefits using a worker’s historical earnings. The monthly benefit amounts are also adjusted annually to account for cost-of-living increases.

- Current projections from the Social Security Trustees show that the OASI Trust Fund for retirement benefits is scheduled to be depleted in 2033, meaning that scheduled benefits will be reduced by 23 percent absent legislative changes. Long-term projections also show that total program costs will exceed total program revenues over the 75-year forecast period.

- The long-term demographic trends of increases in life expectancy and declining birth rates and immigration have contributed to this fiscal imbalance, as retirees collect benefits for longer and there are fewer covered workers per beneficiary paying payroll taxes.

- Congress must summon the political will to negotiate solutions and promptly phase them in to return the program to sound financial footing, give future retirees sufficient time to adjust their financial planning, and preserve benefits for current and future generations.

Introduction

Before the establishment of Social Security, there was no comprehensive, national program to promote economic security in the face of unemployment, illness, disability, and old age. The first relatively widespread program in the United States was the Civil War Pension program for former Union soldiers and their survivors, a significant expenditure for the Federal government in the 1890s accounting for 37 percent of the entire Federal budget in 1894. Around this time, private businesses began instituting company pension plans for their workers, though only about 15 percent of workers had access to these pension plans by the early 1930s.

The period of the late 19th century and early 20th century was defined by the Industrial Revolution, the urbanization of the United States, the decline in the inclusion of the elderly as part of the family household, and significant increases in life expectancy, all of which led to a population that was older and more urban with less access to traditional sources of economic security such as assistance from families. After the financial crash of 1929, during the Great Depression, the US experienced massive unemployment, widespread business failures, and the loss of personal savings, leaving millions destitute. The economic effects fell particularly harshly on the elderly, with one-third to one-half of the elderly dependent on family or friends for economic support.

In response to the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression, various social movements emerged demanding radical reforms to the economic system, including the establishment of old-age pensions for all citizens. Recognizing the need for action, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Committee on Economic Security in 1934, led by Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, to study the problem of economic insecurity and make recommendations for legislation in Congress. The result of these efforts was the Social Security Act of 1935 that established a federally administered system of social insurance for the elderly financed by payroll taxes from employees and their employers. The program now known as Social Security, originally intended as a safety net to supplement lifetime savings, has been expanded over the decades to encompass retirement benefits, disability benefits, and payments to the families of beneficiaries.

Overview of Trust Funds

Social Security consists of two parts:

- The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program provides monthly payments to retired workers, their families, and survivors of deceased workers. As of June 2025, the OASI program paid out $118.1 billion in total monthly benefits to 61.6 million beneficiaries, for an average monthly benefit of $1,916.

- The Disability Insurance (DI) program provides monthly payments to disabled workers and their families. As of June 2025, the DI program paid out $11.8 billion in total monthly benefits to 8.2 million beneficiaries, for an average monthly benefit of $1,443.

Most often, references to “Social Security” are to the OASI program, but the DI program is important as well. Each program has a dedicated Trust Fund from which benefits are paid out. The Trust Funds receive income from payroll tax contributions made by covered employers and employees and from the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits that are subject to the Federal income tax. Employees and employers each pay 5.3 percent in payroll taxes for OASI and 0.9 percent in payroll taxes for DI on earnings up to a fixed amount set annually.

The Department of the Treasury is legally required to invest all Trust Fund income in interest-bearing securities issued by the Federal government, so the Trust Funds also earn interest income from these investments, which accounted for $69 billion of program revenues in 2024. As of 2024, Social Security has collected approximately $29.2 trillion and paid out $26.5 trillion in monthly benefits over the course of the entire program’s history, leaving the Trust Funds with a reserve of approximately $2.7 trillion.

Overview of the Social Security Program

The Social Security Administration (SSA) administers Social Security benefits, including issuing Social Security numbers, tracking eligibility, and calculating benefits. SSA also administers the separate Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program that provides monthly benefits to individuals with limited income and resources who are disabled, blind, or age 65 or older. In addition, the Social Security program has a Board of Trustees that oversees the financial operations of the OASI and DI Trust Funds. The Board of Trustees is composed of six members: the Secretaries of the Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services, the Commissioner of Social Security, and two public representatives appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

Social Security Retirement Benefits

Eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits is tied to “credits” workers earn when they pay Social Security taxes or the self-employment tax. In 2025, workers earn one credit for each $1,810 in earnings, up to a maximum of four credits per year. To be eligible for retirement benefits, workers need 40 credits, or the equivalent of ten years of work.

Family members of retired workers are also eligible to receive Social Security retirement benefits. Spouses can receive benefits if they are age 62 or older or if they are caring for the retired worker’s child. Unmarried children of retired workers can also be paid benefits if they are under 18 years old, a full-time student under 19 years of age, or have a qualifying disability. Under certain circumstances, divorced ex-spouses may be eligible for benefits based on the retired workers’ earnings. Social Security also pays survivor benefits after a retired worker dies to their surviving spouse, unmarried children, and divorced ex-spouses if eligible, usually amounting to 75 to 100 percent of the deceased retiree’s basic retirement benefits. Additionally, there is a total maximum family benefit between 150 to 188 percent of a worker’s benefits.

After an individual completes at least 40 credits of work and becomes eligible for Social Security retirement benefits, the worker may choose among three retirement ages (for the first two, in essence, the date a worker chooses to begin accepting Social Security benefits if otherwise eligible) that determine the amount of benefits the worker can receive:

- The full retirement age is 66 years for individuals born before 1955, between 66 and 67 years of age for workers born between 1955 and 1959, and 67 years of age for workers born in 1960 or later. Choosing to retire at this age means the worker will receive their full benefit amount.

- Workers may choose to retire earlier than their full retirement age and begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits as early as age 62, known as the early retirement age. However, in most cases, SSA permanently reduces benefits by roughly 0.5 percentage points on average for each month a worker chooses to retire before their full retirement age. As an example, a worker with a full retirement age of 67 who chooses to retire at 62 would only receive approximately 70 percent of the Social Security retirement benefit available from retiring at the full retirement age.

- Further, if a worker begins collecting Social Security retirement benefits before their full retirement age and continues working, the worker is subject to the retirement earnings test. For workers attaining their full retirement age after 2025, SSA will withhold $1 in benefits for every $2 of earnings above $23,400. For workers attaining their full retirement age in 2025, SSA will withhold $1 in benefits for every $3 of earnings above $62,160 (only for earnings made in the months prior to the month of full retirement age attainment). Crucially, the worker does not lose these withheld benefits – instead, monthly benefits after the full retirement age are permanently increased to account for the withholdings prior to a worker’s full retirement age, with the beneficiary recouping most or all of the withheld benefits over a typical life span.

- Conversely, workers may delay collecting Social Security retirement benefits after their full retirement age up to age 70, known as the delayed retirement age. For every year after the full retirement age that the worker chooses to delay collecting benefits, SSA will apply a credit and permanently increase the full retirement benefit amount by eight (8) percentage points. To continue the example above, a worker with a full retirement age of 67 who chooses to delay collecting benefits until age 70 will receive approximately 124 percent of their full Social Security retirement benefit.

The goal of these actuarial adjustments to benefits according to retirement age is to provide the worker with roughly the same amount of total lifetime benefits based on average life expectancy.

A worker’s full Social Security benefit amount is known as the primary insurance amount (PIA) and is calculated based on a worker’s historical earnings. SSA first adjusts a worker’s earnings based on the national average wage index to reflect changes in general wage levels that occurred during the worker’s years of employment. SSA then selects the 35 years with the highest indexed earnings, sums the adjusted earnings, and divides the total adjusted earnings by the total number of months in the selected years. The result of this calculation is called the average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). It’s important to note that for workers with fewer than 35 years of earnings in covered employment, years with no earnings count as zeroes in the AIME calculation, so these workers will have a lower AIME and therefore a lower PIA than they would if they had worked 35 years.

To calculate a worker’s PIA, SSA uses the following formula based on three separate percentages of a worker’s AIME, known as “bend points”:

- 90 percent of the first $1,226 of a worker's AIME, plus

- 32 percent of a worker’s AIME between $1,226 and $7,391, plus

- 15 percent of a worker's AIME over $7,391.

The bend point values of $1,226 and $7,391 are for 2025 and are also adjusted annually according to the national average wage index. The table below presents an illustrative example of a worker’s PIA at eligibility based on an AIME of $8,000.

Table 1: Illustrative Example of PIA Calculation for Eligible Worker with AIME of $8,000 in 2025

Finally, before 2025, SSA adjusted an individual’s monthly Social Security benefit if they also received a retirement or disability pension from certain government work not covered by Social Security. These pensions included the Federal civil service, some state or local government employment, or work in a foreign country for which the worker did not pay US Social Security payroll tax. If an individual didn’t pay Social Security payroll taxes on their government or foreign employment earnings, SSA reduced their monthly retirement benefit according to two rules, the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and Government Pension Offset (GPO). The Social Security Fairness Act, enacted in January 2025, eliminated WEP and GPO, increasing Social Security benefits for affected workers.

Once an eligible worker starts collecting Social Security retirement benefits, those benefits are adjusted annually for inflation, known as a Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA), based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which is determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also produces another cost-of-living measure called the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (chained-CPI) that accounts for consumer substitution among item categories in response to changes in relative prices. As discussed in the section on recent challenges below, using chained-CPI as opposed to CPI-W is an option to improve the solvency of the Social Security Trust Funds and bolster the sustainability of the program for future generations.

Figure 1: Comparison of Using CPI-W vs. Chained-CPI for Social Security COLAs

Payroll Taxes and Other Revenue for Social Security

Social Security’s main source of revenue is the payroll tax on employees (including self-employment) and their employers. An estimated 93 percent of workers in paid employment and self-employment are covered under Social Security and must pay these payroll taxes. Under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA), employees and employers each pay 6.2 percent in payroll taxes (5.3 percent for OASI and 0.9 for DI) on earnings up to a fixed amount set annually ($176,100 in 2025), which employers remit to the US Treasury on a regular basis. Under the Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA), self-employed individuals must pay the full 12.4 percent in Social Security payroll taxes on earnings up to the fixed amount ($176,100 in 2025). While the Internal Revenue Service allows self-employed individuals to deduct the employer-equivalent portion of their SECA contributions for Federal income tax purposes, self-employed individuals are effectively taxed higher than those who work for an employer, posing a financial barrier to entrepreneurship.

Figures 2 and 3: Payroll Tax Revenues and Share of US Wages Covered by the Payroll Tax

In 2024, the OASI Trust Fund received net payroll tax contributions of $1,105.6 billion and the DI Trust Fund received net payroll tax contributions of $187.7 billion. An important trend in payroll tax revenues has been the decline in total wages covered under the payroll tax. The ratio of taxable payroll to covered earnings declined from 88.6 percent in 1984 to 82.6 percent in 2020, primarily due to significant increases in income for very high earners as opposed to all other earners. In effect, the growth in earnings at the very top of the income scale has vastly outpaced the growth in the maximum income subject to the payroll tax, causing this drop in the ratio. The ratio has fluctuated over the past 20 years in connection with business cycle changes, settling to an estimated ratio of 83.3 percent in 2023.

In addition, Social Security receives revenue from the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits above a certain threshold. Up to 50 percent of an individual’s Social Security benefits are subject to the Federal income tax if an individual filer reports more than $25,000 in total income or if a joint filer reports more than $32,000 in total income. In 2023, approximately 50 percent of Social Security beneficiaries reported income that exceeded these thresholds and paid Federal income tax on a portion of their benefits, resulting in revenue of $55.1 billion across both the OASI and DI Trust Funds in 2024.

Finally, Social Security receives revenue from the interest the Trust Funds collected by investing in US Treasury securities. In 2024, the combined Trust Fund reserves earned interest at an effective annual rate of 2.5 percent, resulting in interest income of $69.1 billion across both the OASI and DI Trust Funds.

Transfers from the General Fund

Social Security has received transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury in the past as a temporary measure to plug short-term financing issues. For example, Congress enacted a temporary payroll tax cut in 2011 and 2012 to stimulate the economy after the 2008 financial crisis and approved General Fund transfers to reimburse Social Security for the lost revenue. Despite this precedent, using General Fund revenues to finance Social Security in the long term is not a prudent option because the Federal government is already running massive fiscal deficits, which would lead to the issuance of additional Treasury securities at higher interest rates to finance these transfers and an increase in the cost of servicing the debt.

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

As mentioned above, Social Security also provides benefits to individuals who have developed a disability or are blind and have made contributions to the Social Security Trust Funds through payroll taxes. These monthly benefits are known as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and are calculated based on lifetime average earnings covered by Social Security. Individuals must meet Social Security’s disability criteria and may have their benefits reduced if they receive Workers’ Compensation payments and/or other public disability benefits. SSA periodically reviews SSDI cases to assess whether an individual’s condition has medically improved or if that individual can perform substantial gainful activity. SSA provides a variety of work incentives and employment supports to assist individuals on SSDI to return to work or continue working without risking a sudden loss of benefits. Individuals are also entitled to Medicare health benefits if they have received SSDI for 24 months.

Impact of Social Security

Social Security benefits are the largest single source of income among Americans aged 65 and older. For 4 in 10 retirees, Social Security provides at least 50 percent of their income, and for 1 in 7, it provides at least 90 percent. In 2021, 10 percent of adults aged 65 or older had income below the poverty line. Without Social Security, nearly four times as many older Americans (22.4 million) would fall below that line. Thus, Social Security is a key pillar of economic security for older Americans.

Social Security is also extremely popular. In a 2020 AARP survey, 96 percent of those polled regardless of party affiliation said Social Security was either the most important government program or an important one compared with other government programs. More recent YouGov polling from 2023 shows that Social Security had the highest net favorability rating among eight entitlement programs in the United States and that 76 percent of Americans had a favorable view of the program, with these opinions holding regardless of party affiliation.

Current State of the Trust Funds

Since 2010, Social Security has operated under cash-flow deficits, meaning that the amount of monthly benefits paid out has exceeded the amount of tax revenues collected each year. Congress has not acted to change the program since then because lawmakers anticipated that a recovering economy and ample reserves would cover the annual revenue shortfalls. Starting in 2021, total costs for Social Security have exceeded total income (inclusive of payroll taxes, Federal income taxes, and interest income), leading to a net decrease in the reserves for the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds. The Social Security Board of Trustees predicts this trend to continue through the remainder of its 75-year projection period, leading to the depletion of the OASI Trust Fund by 2033. The Congressional Budget Office also predicts the depletion of the OASI Trust Fund by 2033.

Figure 4: Social Security’s Primary OASI Trust Fund Is Projected to Be Depleted by 2033 (Social Security Trust Fund Ratios)

The depletion of the OASI Trust Fund reserve and the fact that scheduled benefits are projected to exceed tax revenues means that Social Security will not have the ability to pay Social Security retirement benefits in full and on time starting in 2034, absent legislative changes. Under current law, SSA is not permitted to transfer funds between the DI Trust Fund and OASI Trust Fund and cannot borrow from the general fund of the Treasury to cover the gap between revenues and scheduled benefits. Thus, on current estimates, Social Security can only pay 77 percent of scheduled OASI retirement benefits in 2034 -- falling from 79 percent last year. A more detailed discussion of the causes of this imbalance and potential options for saving Social Security is presented below.

History of Social Security Reforms

At times, the Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in the history of Social Security. In the mid-1930s, the Supreme Court invalidated major pieces of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, leading the President to advocate for additional powers to appoint new Federal judges, including six new Justices to the Supreme Court. While the President’s proposal was resoundingly rejected by Congress, the nine Justices on the Supreme Court began ruling differently on the constitutionality of New Deal programs. When the constitutionality of the payroll tax was challenged in Helvering v. Davis (1937), the Supreme Court ruled 7 to 2 in support of the OASI program. In 1960, the Supreme Court ruled in Flemming v. Nestor that Social Security is a non-contractual government benefit, meaning that an individual is not automatically entitled to Social Security even if they have paid payroll taxes. The Supreme Court has also granted Social Security eligibility to additional groups, including to widowers in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975). Finally, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Lee (1982) that employers cannot claim a religious exemption under the First Amendment to paying Social Security taxes on behalf of their employees.

After the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935, Congress enacted several reforms over the next fifty years, primarily to expand the program and improve the sustainability of its finances. The first major amendments to Social Security were enacted in 1939 to expand the program to provide benefits to dependents of retired workers (spouses and minor children) and survivors. The 1939 reforms also changed the calculation of benefits to be based on average monthly earnings instead of cumulative wages and reduced the size of required Trust Fund reserves to move the program toward “pay-as-you-go” financing. The Federal government began mailing monthly benefit checks in 1940.

After World War II, inflation reduced the purchasing power of Social Security retirement benefits, and there was a growing recognition of the economic insecurity workers faced from disability (including those who had become disabled in World War II). In response, Congress enacted the first COLA for Social Security benefits in 1950 that provided across-the-board benefit increases and a 77 percent increase to the minimum benefit. Subsequent amendments to the Social Security Act in 1954 and 1956 expanded the number of workers covered under Social Security, leading to approximately 90 percent of workers covered by the mid-1950s. These amendments also instituted a “disability freeze” of a worker’s Social Security record during years of disability to prevent a reduction of benefits for these workers and a new disability benefit for workers aged 50 to 64 and for disabled adult children who had a disability that began before the age of 18 and were survivors or dependents of Social Security beneficiaries. In 1958 and 1960, Congress enacted another series of amendments to expand benefits to disabled workers of any age and their spouses and dependents. Social Security’s finances were relatively strong during this period and into the mid-1970s. OASI Trust Fund asset reserves grew or only declined by less than 10 percent throughout the period. The ratio of OASI asset reserves to program costs was also approximately 100 or above until 1970, meaning that the reserves in the OASI Trust Fund could fully cover at least one year of Social Security program costs.

The next significant amendment to Social Security was in 1972 to establish automatic COLAs in response to the strong inflation of the period. However, the calculation of COLAs for benefits was coupled with an adjustment to account for wage increases that resulted in immediate financing challenges for the program when combined with the negative economic conditions of the 1970s. Congress passed another set of amendments in 1977 to address the financing of Social Security by gradually raising the payroll tax to its current levels, increasing the wage base, reducing benefits slightly, enacting the GPO rule, and decoupling wage adjustments from benefit COLAs.

Figure 5: Benefit Payments Exceeding Payroll Tax Revenues Has Historically Preceded Reforms

Despite these reforms, Social Security faced both a short-term financing crisis and a long-term solvency issue in the early 1980s, primarily due to high inflation, significant unemployment, and stagnant wages. The combined balances of the OASDI Trust Funds peaked at $45.9 billion in 1974 before declining precipitously to $16.9 billion by the end of October 1982. The balance in the OASI Trust Fund for retirement benefits was so low in the Fall of 1982 that the OASI Trust Fund was forced to borrow from the DI Trust Fund and Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund to fully pay scheduled benefits. Long-term demographic projections also revealed that increases in life expectancy and declines in birth rates would further strain the program’s finances in the future.

To address the financing crisis, President Reagan appointed the National Commission on Social Security Reform led by Alan Greenspan to study the issue and recommend reforms to Congress. The Greenspan Commission was established due to “the continuing deterioration of the financial position of the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, the inability of the President and the Congress to agree to a solution, and the concern about eroding public confidence in the Social Security system.” The Commission consisted of 15 members appointed on a bipartisan basis, with five selected by each of the President, the Senate Majority Leader, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The resulting legislation, the Social Security Amendments of 1983, represented the last major reform of the program to date. These amendments gradually raised the full retirement age to 67 over a period of 40 years, accelerated the payroll tax increases enacted in 1977, permanently increased self-employment payroll tax rates, made half of Social Security benefits taxable under the Federal income tax for certain high-income beneficiaries, and enacted the WEP rule (now repealed in the Social Security Fairness Act in 2025).

Reforms after 1983 focused largely on work requirements and work incentives for beneficiaries receiving SSDI and SSI benefits. In 2000, Congress repealed the retirement earnings test for beneficiaries at or above the full retirement age. President George W. Bush made Social Security reform a top priority of his Administration, even appointing a commission in 2001 to study the issue and make recommendations. However, Congress did not enact any major changes to Social Security after 2000.

Recent Challenges and Urgent Need for Legislative Action

As in the early 1980s, Social Security today faces challenges to both its short-term financing and long-term solvency due to demographic trends. Life expectancy at birth has increased dramatically in the United States since 1940, going from 61.4 years for men and 65.7 years for women to 76.6 years for men and 81.5 years for women in 2024. Given these increases are closely tied to declining infant mortality, a better measure is life expectancy at age 65, which is near the full retirement age for Social Security. In 1940, men could be expected to live an additional 11.9 years at 65 and women could be expected to live an additional 13.4 years at 65. In 2024, men could be expected to live an additional 18.3 years at 65 and women an additional 20.9 years at 65. These increases in life expectancy mean that Social Security is paying out benefits longer to retired workers.

Over the same period, the total fertility rate has decreased, meaning women are giving birth to fewer children. In 1940, the total fertility rate, or the average number of children born to a woman, was 2.23, increasing to 3.61 by 1960 due to the Baby Boom generation. Since then, the total fertility rate has declined to 1.62 in 2024. This decline in population growth has caused the ratio of covered workers per OASDI beneficiary to decrease concomitantly, as shown below. In 1960, this ratio was 5.1 covered workers per beneficiary; in 2024, this ratio has decreased to 2.7 covered workers per beneficiary. As such, there are fewer workers paying into Social Security for every beneficiary receiving monthly payments. (Increased legal immigration could make up for the difference from declining fertility rates, increasing the ratio of covered workers per beneficiary.)

Figure 6: Covered Workers per OASDI Beneficiary (Historical and Projected)

These two trends combine to cause a deteriorating financial picture for Social Security, as both the Social Security Board of Trustees and CBO predict the OASI Trust Fund will be depleted by 2033 absent legislative action. The Trustees also predict total costs to exceed total revenues throughout their 75-year projection period. The American public’s confidence in the solvency of Social Security reflects these worrisome trends. In Gallup polling from 2023, 47 percent of non-retirees believe the Social Security system will not be able to pay them a benefit when they retire and 43 percent of retirees believe there will eventually be cuts in their benefits. Respondents also worried a “great deal” (45 percent) or a “fair amount” (29 percent) about the Social Security system.

Social Security is also an important component of the Federal budget and US GDP, and the program’s finances therefore have significant effects on the national debt and the American economy. Some advocates and commentators have argued that Social Security should not be considered as contributing to the deficit because by law, Social Security can only pay benefits from its Trust Funds. Once the Trust Fund reserves are depleted, Social Security is currently limited to paying benefits that are covered by incoming revenues (payroll taxes and income taxes on a portion of Social Security benefits). Nevertheless, this perspective ignores the size of Social Security in relation to overall Federal outlays and receipts and overall GDP. In 2025, estimated revenues to Social Security are 4.7 percent of GDP and comprise more than 27 percent of Federal receipts. Social Security outlays are also estimated to be 5.3 percent of GDP in 2025 and 23 percent of total Federal outlays, according to CBO’s latest estimates.

Because of this impact on the economy, both the President’s annual Budget and CBO adopt a “unified budget framework” that includes Social Security to provide a more comprehensive picture of the size of the Federal government and the budget’s impact on the economy. This unified framework is also how investors in Treasury securities assess the ability of the US government to fulfill its obligations and repay its debts. Social Security is an entitlement and commitment from the Federal government to retirees and other eligible beneficiaries. As the costs of servicing the national debt increase, investors in the market will take a comprehensive view of the Federal government’s financial position when making their decisions on buying and selling US Treasury securities, thereby affecting market interest rates and the broader economy.

Given the financial challenges facing Social Security, Congress must urgently act to address the financial imbalances, both in the short-term and the long-term. SSA, CBO, and other organizations like the American Academy of Actuaries have released options for saving Social Security, which CED has summarized in its Solutions Brief on Social Security. These options can be grouped into three categories:

- Benefit adjustments: These options would reduce the costs of the Social Security program to ensure that future generations of retirees can still collect close to the full scheduled benefits. Benefit adjustments include gradually raising the full retirement age to 69 and the delayed retirement age to 72 while continuing to allow for early retirement at 62, implementing modest means testing for high-income beneficiaries, using chained-CPI instead of CPI-W for COLAs, and removing work disincentives for retirees.

- Revenue raisers: These options would bolster the income that the Social Security Trust Funds receive to restore a positive cash flow and rebuild Trust Fund reserves. Payroll taxes could be gradually increased to bring in additional revenue, though these taxes are regressive for low-income workers and disproportionately impact self-employed individuals that drive American entrepreneurship. The maximum taxable earnings of $176,100 for the payroll tax could be increased or eliminated to restore total payroll tax revenues to a higher percentage (for instance, 90 percent) of total US income, as it was in 1983 at the time of the last major reforms. Newly hired state and local workers could also be covered under Social Security to cover more wages under the payroll tax.

- Diversifying Trust Fund investments: Currently, reserves in the Trust Funds must be invested in US Treasury securities, which typically have lower returns than other investments such as index funds that track the major stock market indices. Changing the law to allow for investments beyond Treasury securities could increase the interest income the Trust Funds make and bolster revenues while also raising significant questions about how these funds would be managed.

Apart from a sizeable increase in the payroll tax, none of these options by themselves fully addresses the short-term and long-term challenges facing Social Security. As such, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress must also protect vulnerable populations of retirees by increasing the minimum benefit to protect low-wage workers and those with intermittent careers and by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide Americans approaching retirement with sufficient time to adjust their retirement planning.

Conclusion

Social Security is a vital and immensely popular program that supports retired workers, their families, and individuals with disabilities. Given the impending depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund that supports retirement benefits over the next decade, it is crucial that Congress addresses this issue quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to Social Security. The longer the delays, the greater the chances that the necessary legislative changes to save Social Security will be disruptive to beneficiaries and the broader economy.

For further reading