The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) operates programs to support farmers, vulnerable populations in need of nutrition assistance, and the overall food and agricultural system. These programs offer important benefits and services, providing a safety net for farmers and households with nutritional needs. However, it is also important to consider the fiscal context: because the US national debt has recently reached a record $38.4 trillion and government spending exceeded government revenues by $1.8 trillion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2025, the US’ overall fiscal condition threatens the fiscal foundation that supports farmers and other vital government services. As a significant component of Federal spending, it is important to consider USDA’s programs as part of a holistic evaluation of the Federal government’s fiscal position, with a goal to reverse its negative trajectory while maintaining crucial agriculture and nutrition programs. Indeed, only through setting the country on a sounder fiscal footing will the US be able to maintain the safety net it has promised to farmers and households in need of nutrition assistance.

This Explainer provides a brief introduction to USDA’s mission areas; an overview of USDA’s agriculture, nutrition, and other programs; descriptions of the farm bill that authorizes many of these programs and USDA’s budget; and a discussion of some options prepared by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) for reforms to USDA’s programs that would serve to reduce the national debt.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) comprises 29 agencies and offices with almost 100,000 employees at more than 4,500 locations nationwide and abroad.1 USDA implements farm production and conservation programs designed to mitigate the significant risks of farming through crop insurance, conservation programs, farm safety net programs, lending, and disaster programs.2 USDA also provides food, nutrition, and consumer services through the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), which administers Federal domestic nutrition assistance programs and includes the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion.3 USDA’s other mission areas include: the safety of meat, poultry, and egg products; facilitating domestic and international marketing of US agricultural products; regulating plant and animal health and welfare; managing the productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands; conducting research, education, and economic analyses of the US food and fiber system; promoting rural development (including expanding access to high-speed internet, electric, and transportation infrastructure); and trade policy and research on international crops and agricultural issues.4 Finally, USDA recognizes the important role of US agriculture and domestic food production in national security through its National Farm Security Action Plan.5 The plan outlines USDA’s leadership in securing agricultural supply chains, preventing nutrition benefits fraud, and protecting animals and soil from biothreats, with a particular emphasis on addressing threats from foreign countries of concern and their purchase of US agricultural land.6

Congress and President Lincoln established USDA in 1862, cementing the importance of agriculture to American life and the US economy.7 The proportion of farmers in the US workforce declined from 90% in 1790 to 64% in 1850 because of increased labor productivity and crop yields resulting from technological advances and mechanization, such as the invention of the horse-drawn reaper and the cotton gin. Agriculture in the South was heavily reliant on slave labor before the Civil War, and agricultural exports were roughly 65% of total US exports in 1850. In the second half of the 19th century, consumer demands for higher food safety became an important issue for Federal policymakers as employment in agriculture continued to decline. By the 1930s, USDA played a large role in research to address the droughts of the time that led to the Dust Bowl, and Congress passed the first version of the modern farm bill in 1948. Continued advancements in labor productivity and crop yields through the second half of the 20th century led to a persistent decline in the share of farmers as a percentage of the US workforce, eventually dropping to 2.6% by the 1990s. Nevertheless, USDA remains a prominent Federal agency as a crucial support for farmers and the administrator of vital nutrition programs for vulnerable Americans.

USDA’s two major areas of focus are agriculture8 and nutrition9 programs, though USDA also operates programs related to food safety, research, conservation, and forestry management. The farm bill (discussed more below) authorizes many of these programs, with the rest authorized by other legislation and funded through discretionary or supplemental appropriations.

USDA operates various safety net programs to provide risk protection and income support to US farmers experiencing natural disasters, adverse growing conditions, or low market prices.10 Production, weather, and/or market conditions automatically trigger these payments. Farm safety net programs fall into three broad categories: the Federal crop insurance program (FCIP), standing agricultural disaster programs, and agricultural commodity support programs. The first two programs are permanently authorized under various laws, while the commodity support programs are authorized through the farm bill.

The FCIP provides insurance coverage for most field crops, many specialty crops, certain livestock and animal products, and grazing lands.11 While FCIP is permanently authorized, any policy changes to the program are included in the farm bill. CBO projects baseline outlays for the FCIP to be $123.5 billion between FY2025 and FY2034,12 and total FCIP outlays (premium subsidies, program delivery costs, and underwriting gains) in FY2024 were approximately $15 billion.13 The program offers agricultural producers financial protection for over 130 agricultural commodities against losses resulting from adverse events and covers an average of 284 million acres annually.14 Farmers customize their coverage to meet their specific needs and receive premium subsidies from USDA depending on the coverage purchased. USDA fully subsidizes premiums for catastrophic-only coverage, with farmers responsible only for an administrative fee. Farmers pay a larger share of premiums for higher levels of coverage, up to a maximum of 62% of the total premium.

FCIP policies insure agricultural commodities against losses due to unavoidable natural events or, in specified cases, seasonal market price declines.15 Farmers must follow USDA guidance on best farm management practices to maintain coverage eligibility. USDA regulates the policies offered by Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs) and their pricing. USDA also offers program delivery subsidies to the AIPs to compensate for the cost of selling and servicing FCIP policies and reinsures a portion of the policies sold per the terms of two annual agreements between USDA and the AIPs (the Standard Reinsurance Agreement and the Livestock Price Reinsurance Agreement). Over the years, Congress has expanded the FCIP to cover additional commodities and risks. The number of AIPs has also declined over time due to consolidation in the insurance industry.

USDA also administers several Federal programs – including the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP), livestock and fruit tree disaster programs, and ad hoc assistance – to help agricultural producers recover from natural disasters.16 Outside of ad hoc assistance, these programs are permanently authorized and receive “such sums as necessary” from the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). In six of the eight fiscal years between FY2018 and FY2025, Congress has also authorized a total of nearly $40 billion in ad hoc assistance via supplemental appropriations to assist with natural disaster losses generally not covered by permanent programs.

NAP is designed for agricultural producers who grow a crop that is currently ineligible for standard crop insurance policies.17 “Basic” NAP coverage insures against catastrophic losses, defined as losses more than 50% of normal yield. Producers pay an administrative service fee, and basic NAP has an annual payout limit of $125,000 per crop year per producer for basic coverage. Producers can also purchase higher coverage levels for less severe losses, known as “buy-up” coverage. For this coverage, agricultural producers pay the NAP service fee and a premium to cover losses between 50% and 65% of a crop lost. NAP buy-up coverage has an annual payout limit of $300,000 per crop year per producer. For both types of NAP coverage, policies must be purchased prior to a disaster event, and producers must purchase or renew coverage on an annual basis. A producer is ineligible under NAP if the producer's average annual adjusted gross income (AGI) exceeds $900,000.

In addition, USDA operates four permanently authorized agricultural disaster programs for livestock and fruit trees: Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP); Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP); Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP); and Tree Assistance Program (TAP).18 These programs provide compensation for a portion of lost production following a natural disaster and producers do not pay a fee to participate. Payments for individual producers under LFP may not exceed $125,000 per year. There are no limits on the dollar amount of payments received under LIP, ELAP, and TAP. To be eligible for a payment under any of these programs, a producer's average annual AGI over three recent taxable years cannot exceed $900,000.

USDA administers three main commodity programs19 authorized by the farm bill.20 The farm bill authorizes these programs to provide price support and disaster assistance for major commodity crops, such as wheat, corn, soybeans, peanuts, rice, dairy, and sugar. CBO projects baseline outlays for USDA’s commodity programs to be $72.5 billion between FY2025 and FY2034.21 The Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program makes payments to farmers when the effective price of a covered commodity is less than the effective reference price for that commodity, which is tied to the statutory reference prices set by the farm bill. Payments are proportional to an individual producer's base acres and payment yields. The Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) program provides income support to farmers when crop revenue falls below a set guarantee for covered commodities. ARC coverage can be at the county-level or individual-level and payments are made based on historical county or farm revenues, respectively.22 The CCC funds the PLC and ARC programs, which receive mandatory appropriations of "such sums as necessary.”23 These programs do not charge any participation fees, are subject to annual payment limits, and producers must meet eligibility requirements to participate. PLC coverage cannot be combined with ARC coverage for the same commodity. Total ARC and PLC support for farmers is estimated to be $2.6 billion for the 2024 crop year,24 and USDA provided an additional $10 billion for commodity support through the Emergency Commodity Assistance Program25 and $20 billion in supplemental disaster assistance in 2024.26

Since the 1930s, the Marketing Assistance Loan (MAL) program allows agricultural producers to use eligible commodities they have produced as collateral for government-issued loans.27 The program helps farmers meet cash flow needs by providing financing for commodities pledged as collateral, allowing farmers to delay sales until later in the marketing year when market conditions may improve.28 In addition, USDA operates the Loan Deficiency Payment (LDP) program, which provides payments to farmers eligible to receive price support under the MAL program.29 When market prices fall below the MAL rates, the LDP program may provide direct payments to producers equal to the amount of MAL marketing loan gains (the difference between the lower market price and the higher MAL rate). Farmers cannot receive MAL and LDP program benefits for the same commodity and must meet eligibility requirements. USDA also administers a Dairy Margin Coverage program to provide milk producers with a guaranteed margin for their milk production.30

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides nutrition assistance to eligible, low-income individuals and households via a monthly benefit on an Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) card.31 FNS administers SNAP and approximately 95 percent of outlays are for the benefits themselves.32 States determine eligibility and issue benefits to eligible households, but the Federal government fully funds SNAP benefits.

The farm bill authorizes SNAP and other nutrition programs,33 including the Emergency Food Assistance Program,34 which helps supplement the diets of low-income Americans via food assistance delivered by food banks and other local organizations, and the Commodity Supplemental Food Program,35 which provides monthly food packages to low-income seniors. CBO projects baseline Nutrition program outlays authorized in the farm bill to total $1.1 trillion between FY2025 and FY2034,36 and Federal spending on USDA’s food and nutrition assistance programs totaled $142 billion in FY2024.37

Formerly known as the Food Stamp Program, SNAP aims to boost the food-buying power of low-income households to be able to afford a nutritionally adequate, low-cost diet.38 Households qualify for SNAP by meeting certain income and asset tests, either through a “traditional eligibility” pathway or via “categorical eligibility.” Under traditional eligibility, a household must pass tests for gross income, net income, and assets. Under categorical eligibility, households may automatically qualify if they already receive other forms of means-tested assistance (for example, benefits under certain Federal assistance programs), and states have the option to expand access through “broad-based categorical eligibility.” Benefits issued on an EBT card are strictly redeemable for food, not cash, and only at licensed retailers that meet USDA requirements.

The farm bill also authorizes various nutrition assistance programs for specific locations and populations.39 Nutrition Assistance Block Grants are capped funding for Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands to administer respective nutrition programs under terms negotiated with Memoranda of Understanding with USDA. The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations provides, in lieu of SNAP benefits, food commodities to low-income households on Indian reservations and to Native American families residing in Oklahoma or in designated areas near Oklahoma. The Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program provides vouchers and coupons to low-income seniors to purchase fresh produce at farmers' markets and other direct-to-consumer venues. USDA also administers competitive grants for projects to improve access to locally produced food for low-income households (Community Food Projects) and to increase the purchase of fruits and vegetables via SNAP incentives and “produce prescriptions” to SNAP and Medicaid beneficiaries (Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program).

USDA also operates two major nutrition programs that are authorized outside of the farm bill. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides healthy foods, personalized nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to other services to support pregnant women and those with children under five years of age.40 WIC is available to women who are currently pregnant, postpartum (up to 6 months after the ?end of a pregnancy?), or breastfeeding (up to the infant’s first birthday); infants; and children up to their fifth birthday.41 Applicants must meet income eligibility limits that vary by household size, apply through a local WIC agency, and receive a nutrition assessment before completing enrollment.42 Once enrolled, WIC recipients can purchase healthy foods using an eWIC card (similar to a debit card), receive nutrition education (shopping advice, meal planning, assistance with food allergies and special dietary needs), receive breastfeeding support, and connect with community-based services, such as medical and mental health care and food banks.43

Another set of programs focus on child nutrition and meals for schools and childcare facilities.44 The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is a Federally assisted meal program operating in public and nonprofit private schools and residential childcare institutions.45 Established by the National School Lunch Act in 1946, NSLP provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free lunches to children each school day. FNS administers the program alongside state agencies through agreements with school food authorities (public or nonprofit private schools at the high school level or below or residential childcare institutions).46 Children may be determined “categorically eligible” for free meals through participation in certain Federal assistance programs or they may qualify for free or reduced-price meals based on household income and family size.47

The School Breakfast Program (SBP) provides reimbursement to states to operate nonprofit breakfast programs in schools and residential childcare institutions.48 FNS administers the SBP at the Federal level. State education agencies administer the SBP at the state level, and local school food authorities operate the program in schools. USDA also provides meals and snacks during the Summer at no cost at schools, parks, and other neighborhood locations through the Summer Food Service Program (also known as SUN Meals).49 The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) is a Federal program that provides reimbursements for nutritious meals and snacks to eligible children and adults who are enrolled for care at participating childcare centers, day care homes, and adult day care centers.50 Finally, the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP) provides a variety of free, fresh fruit and vegetable snacks to children at eligible elementary schools.51

Outside of these major agriculture and nutrition programs, USDA performs a host of other functions related to the US food system.52 Conservation programs encourage environmental stewardship and improved management of farmlands through land retirement and working lands programs. USDA administers a variety of incentive-based conservation programs for agricultural producers to promote soil health, water and air quality, wildlife habitats, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.53 These initiatives often take the form of working land programs that provide financial and technical assistance to farmers who adopt, install, or maintain conservation practices on land in agricultural production. The programs also provide easements or contracts to remove land from agricultural production to preserve and restore natural habitats. CBO projects baseline outlays for conservation programs to total $58.4 billion between FY2025 and FY2034,54 and USDA spent an estimated $5.7 billion on its major conservation programs in FY2024.55

Trade programs support U.S. agricultural exports and international food assistance. Credit programs offer direct government loans and guarantees to producers to buy land and operate farms and ranches. Rural development efforts support rural housing, community facilities, business, and utility programs through grants, loans, and guarantees. USDA also supports agricultural research and extension programs to expand academic knowledge and help producers be more productive, and forestry management programs run by the Forest Service. Energy programs encourage the development of farm and community renewable energy systems through grants and loan guarantees. Horticulture programs support the production of specialty crops, USDA-certified organic foods, and locally produced foods and authorize a regulatory framework for industrial hemp. Finally, USDA operates programs and assistance for livestock and poultry production, support for beginning farmers and ranchers, and food safety initiatives, such as the inspection of domestic products, imports, and exports, conducting risk assessments, and public education.56

Public Law 119-21 (H.R. 1, 2025),57 also referred to as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” or OBBBA, made significant changes to USDA programs,58 largely increasing appropriations on agriculture programs while reducing spending on nutrition programs over the next decade.59 OBBBA invests $65.6 billion into the farm safety net by updating the ARC and PLC programs and increasing reference prices and commodity loan rates to better reflect current higher production costs and market conditions. OBBBA also implements major tax provisions benefitting agricultural producers, such as the immediate expensing of farm equipment, a small business tax break, and an increase in the estate tax exemption. In addition, the legislation includes several key measures that benefit the biodiesel industry, including an extension of the 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit through the end of 2029 (applying it only to feedstocks from the US, Canada, and Mexico) and an expansion of the small agri-biodiesel producer tax credit from 10 cents to 20 cents a gallon. Regarding SNAP, OBBBA establishes a cost-share program proportional to state payment error rates to incentivize states to address benefits fraud. States will be required to contribute a set percentage of the cost of SNAP benefits beginning in fiscal year 2028 if their payment error rate exceeds 6% (defined as the percentage of benefit dollars above or below what program rules direct,60 i.e., the sum of the percentage of overpayments and underpayments61). OBBBA is projected to cut spending on food aid by $186 billion, with the majority coming from cuts to SNAP.

From FY2019 to FY2023, USDA distributed $161 billion in financial assistance to agricultural producers, of which 42% was supplemental assistance to producers affected by international trade disruptions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and natural disasters and 33% was crop insurance.62 USDA provided financial assistance to an average of 1 million agricultural producers annually during this period. However, the distribution of benefits is highly unequal. Approximately 93% of producers received a combined annual average of $11.9 billion in financial assistance (or about $12,000 per producer) while the other 7% received a combined annual average of $20.3 billion (or about $272,000 per producer). The top 10 producers received about $18 million annually on average, while the top producer received $215.2 million in 2022. Over this five-year period, historically underserved producers participating in USDA financial assistance programs increased from 84,000 to 183,000 and the number of participating livestock and poultry producers increased from about 76,000 to 243,000.

One in four Americans participate in one of the USDA’s 16 nutrition assistance programs annually.63 In FY2024, SNAP served an average of 41.7 million participants per month with an average monthly benefit of $187.20, and 12.3% of all US residents received SNAP benefits that year.64 SNAP participation varies widely by state, with the share of residents receiving SNAP ranging from 21.2% to 4.8% of a state’s population. In FY2023, roughly 42% of SNAP recipients were adults ages 18 to 59, 28% were children ages 5 to 17, and 20% were adults ages 60 or older.65 WIC provided monthly benefits to approximately 6.6 million participants in FY2023 and the NSLP served more than 4.6 billion school lunches that year.66 Since the NSLP’s inception in 1969, the share of lunches served for free or at a reduced price rose from 15% in FY1969 to 74% in FY2019.67

The farm bill68 is a comprehensive package of laws that authorizes and governs the agricultural and nutrition programs USDA administers.69 The farm bill is typically authorized every five years and includes both mandatory spending on programs including nutrition assistance and crop insurance and the parameters for discretionary appropriations that are usually included in separate appropriations bills for programs including rural development and research.70

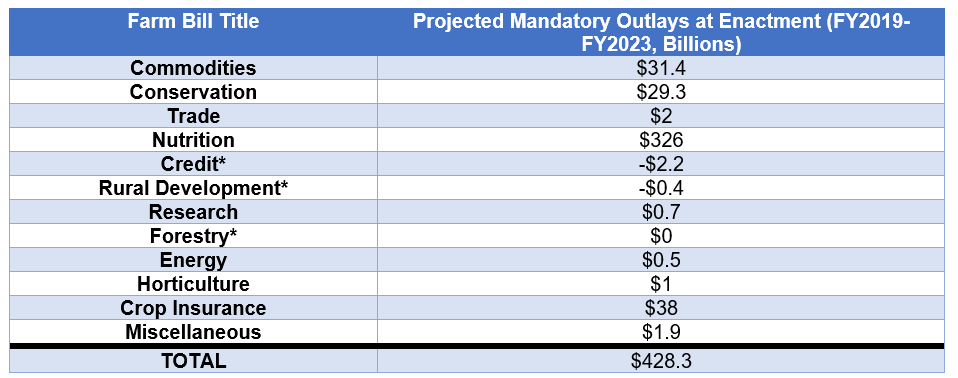

Figure 1: 2018 Farm Bill Total Projected Mandatory Outlays at Enactment (FY2019 – FY2023)

Sources: What Is the Farm Bill?, Congressional Research Service, April 9, 2024; The Conference Board, 2025.

*Notes: “Credit” baseline outlays are negative because of receipts to the Farm Credit System Insurance Fund. “Rural Development” baseline is negative because other appropriations for the program are accounted for outside of the farm bill. “Forestry” baseline outlays are $5 million (round down to 0).

Congress enacted the current farm bill in 2018 and passed a one-year extension for both FY2024 and FY2025.71 While Congress typically renews the farm bill every five years, CBO projects baseline outlays for the programs in the farm bill to total approximately $1.36 trillion between FY2025 and FY2034 (its standard ten-year timeframe for estimating budgetary impacts).72 The farm bill contains 12 titles, of which four (Nutrition, Crop Insurance, Commodities, and Conservation) represent the vast majority of baseline mandatory spending over the next ten years. The farm bill also authorizes programs that support US agricultural exports and international food assistance, direct government loans and guarantees to agricultural producers, rural development initiatives, agricultural research and extension, forestry management, renewable energy, and horticulture.73

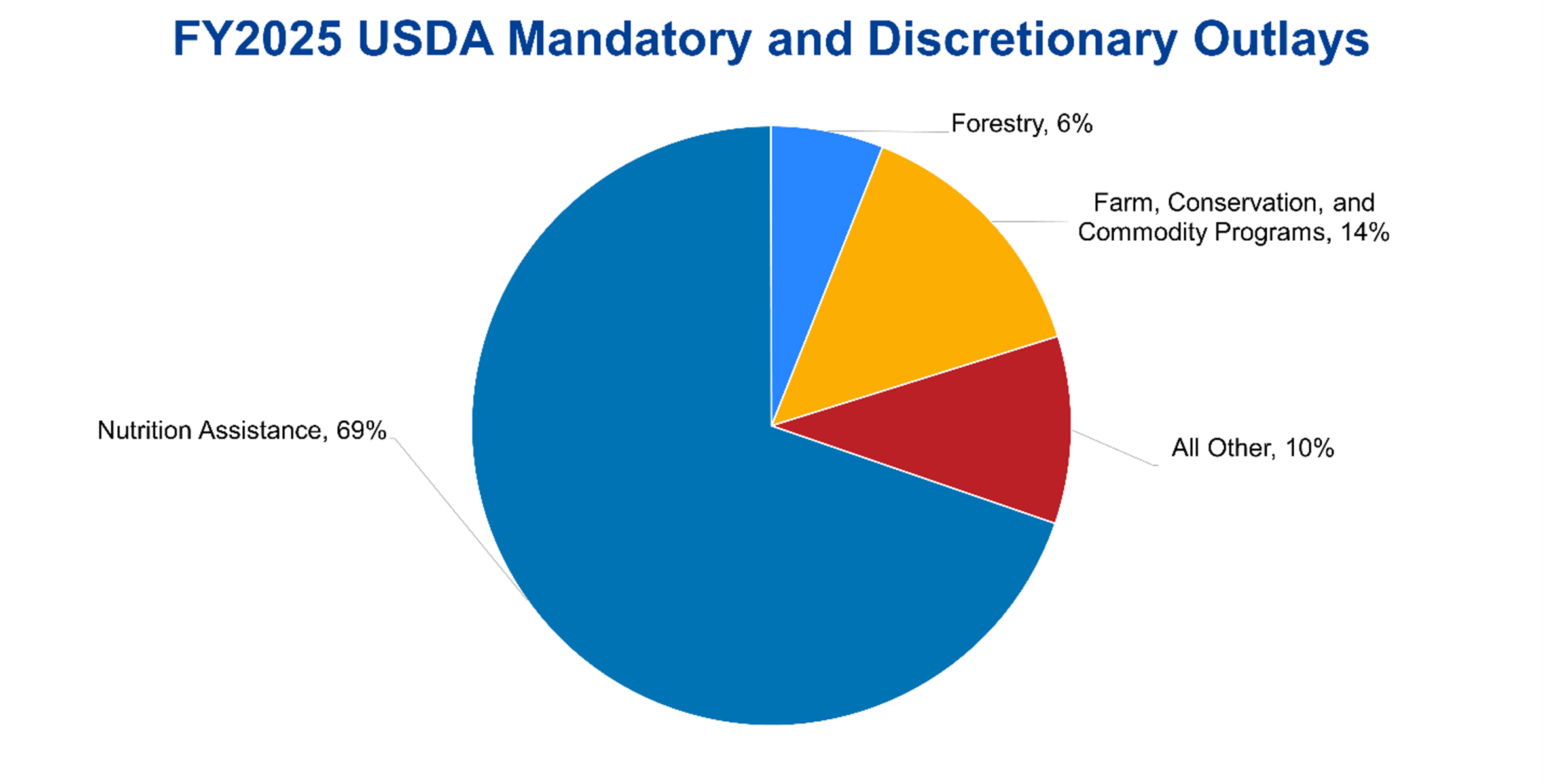

Under current law, USDA’s outlays in FY2025 were $231 billion.74 Mandatory programs comprised nearly $190 billion or 82% of outlays, while the remaining $41 billion or 18% of outlays were for discretionary programs. Mandatory outlays include crop insurance, most nutrition assistance programs, farm commodity and trade programs, and a number of conservation programs. Discretionary programs include WIC, food safety, rural development loans and grants, research and education, soil and water conservation technical assistance, animal and plant health, management of national forests, wildland firefighting, other Forest Service activities, and domestic and international marketing assistance.

Figure 2: Breakdown of FY2025 Outlays for USDA

Sources: USDA FY2025 Budget Summary; The Conference Board, 2025.

Note: “All Other” includes Rural Development, Research, Food Safety, Marketing and Regulatory, and Departmental Management.

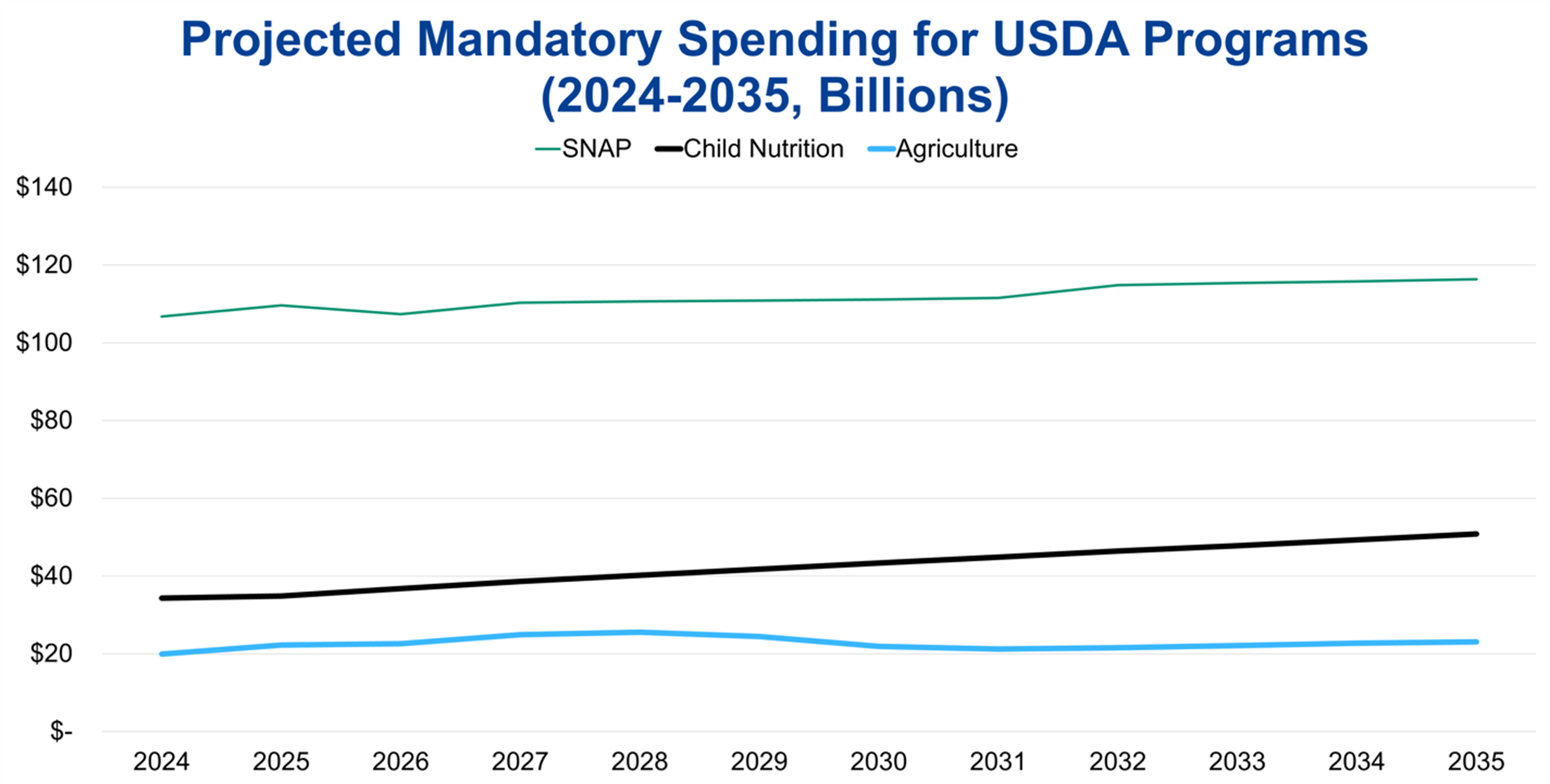

Additionally, CBO releases projections for three major USDA programs in its ten-year budget baseline.75 As demonstrated in the chart below, child nutrition program spending is expected to grow significantly over the next ten years, while SNAP outlays are projected to grow at a more modest level and agriculture program spending is expected to remain relatively flat during the same period.

Figure 3: CBO Projections of Major USDA Programs

Sources: The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, January 2025; The Conference Board, 2025.

The Federal government’s rising spending on USDA programs comes in the context of the unsustainable US national debt, which recently reached a record $38.4 trillion.76 Government spending also exceeded government revenues by $1.8 trillion in FY2025.77 To finance this increasing spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities, which could include the discretionary portion of USDA’s budget.78 As such, Congress can consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress should also protect farmers, nutrition program beneficiaries, their families, and other stakeholders by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide them sufficient time to adjust.

CBO, the nonpartisan agency that produces independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process, has described several options that would produce large reductions to the deficit (each option would require a statutory change).79 Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs from these policies to balance the decreases in spending with the reductions in coverage and benefits under the affected USDA programs.

The first set of options concerns FCIP.80 USDA currently pays roughly 60% of total premiums (on average), while farmers pay about 40%. The Department also imposes limits on its reimbursement of administrative expenses for the private insurance companies (AIPs) that sell insurance products through the program. These expenses are expected to be $2.4-$2.5 billion annually over the next decade. One option would reduce the Federal share of total crop insurance premiums to 40 percent (on average), resulting in a reduction in the deficit of $32.7 billion between 2025 and 2034. Another option would limit reimbursement to AIPs for administrative expenses to an average of 9.25% of estimated premiums, or roughly $1.5 billion annually from 2026 to 2034, producing a deficit reduction of $14 billion over the next decade.

Regarding the farmer safety net, Congress has recently decided to increase subsidies to farmers through the agricultural policy changes in OBBBA.81 Some economists have questioned the utility and cost of these subsidies, particularly in light of our Nation’s fiscal challenges and the lack of similar Federal government support for other industries that comprise a much larger portion of the US economy.82 Given the large proportion of these subsidies that go to high-income agricultural producers, Congress may consider implementing income caps and targeting these subsidies to smaller producers that would not remain financially viable but for government support.83 The Federal intervention in the agricultural market also distorts the incentives for agricultural producers, leading to a US agricultural system that produces a majority of crops that are not for human consumption (instead being used to feed livestock, produce ethanol for fuel, or produce oils to be used in processed foods).84 Climate change, environmental, and nutritional concerns about the US food production system also provide an impetus for Congress to reassess its policy of increasing subsidies for monoculture commodity crops instead of diversifying crops and producing more healthy fruits and vegetables for human consumption.

Another option CBO analyzed concerns subsidies for meals served through the NSLP, the SBP, and in child and adult care centers through the CACFP.85 Currently, USDA subsidizes all meals served, with greater subsidies for meals served to beneficiaries from households with income at or below 185% of the Federal poverty level (FPL). This option would eliminate subsidies for meals served to program participants with household income greater than 185% of the FPL, producing a reduction in the deficit of $14.1 billion between 2025 and 2034. The option does not apply to meals served in schools participating in the Community Eligibility Provision and CACFP participants in day care homes.

Regarding USDA’s nutrition programs, Congress has focused on reducing Federal spending on SNAP through policy changes in OBBBA that introduce cost-sharing with states, increase state administrative costs, prohibit noninflationary increases in the Thrifty Food Plan used to set SNAP benefit rates, and increase work requirements.86 While these reforms reduce Federal spending, some of these costs are shifted to state budgets which are much more constrained87 and millions of SNAP beneficiaries are at risk of losing benefits.88 Through the Make America Healthy Again Commission, the Administration is also emphasizing healthy eating with a focus on reducing childhood chronic diseases by investing in research, streamlining regulations, increasing public awareness and education, and collaborating with the private sector.89 SNAP’s healthy incentives programs are a reflection of this push to use nutrition to reduce chronic disease and its associated healthcare expenditures.90 Targeting healthier foods to decrease healthcare expenditures may be a more sustainable method to use nutrition policy to indirectly reduce overall Federal expenditures on Medicare and Medicaid, and a bipartisan group of Senators recently urged the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to expand access to medically-tailored meals to improve health outcomes and generate cost savings.91

USDA should also take steps to improve the efficiency and integrity of its programs and operations, as outlined in recent recommendations from USDA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG).92 Over the past several years, OIG has reviewed USDA’s operations regarding the safety of the food supply, animal welfare, IT security and management, the integrity of program benefits, financial management and accountability, property management, employee integrity, and oversight of supplemental funding provided by Congress.93 Of particular concern for OIG is the process FNS uses to disburse SNAP benefits via the EBT system.94 OIG evaluated FNS’s fraud risk assessment process for SNAP EBT and found that FNS was forced to replace over $220 million in stolen SNAP EBT benefits (often stolen via electronic methods, such as card-skimming schemes) with Federal funds across FY2023 and FY2024.95 FNS has not yet implemented the Government Accountability Office’s Fraud Risk Management Framework, has not comprehensively assessed SNAP fraud risks, and has not documented a prioritized approach to managing fraud risks. USDA should implement OIG’s recommendations regarding SNAP fraud risk assessment, including designating a dedicated fraud risk management entity, comprehensively assessing fraud risks, documenting the fraud risk profile, and designing and implementing an anti-fraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile.

USDA’s programs are crucial supports for farmers and vulnerable populations, providing a vital safety net that recognizes the importance of agriculture and the food system to the Nation. In the context of the Federal government’s deteriorating fiscal position and unsustainable national debt, Congress must holistically evaluate opportunities for reform throughout the Federal government and address these negative fiscal trends quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to USDA’s programs. The longer the delays, the greater the chance that necessary legislative changes to preserve agricultural and nutrition programs will be disruptive to farmers, vulnerable households, and the communities in which they live.

[i] U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). “About USDA” and “Agencies”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[ii] USDA. “Mission Areas”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[iii] USDA. “Mission Areas”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[iv] USDA. “Mission Areas”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[v] USDA. “Farm Security is National Security: The Trump Administration Takes Bold Action to Elevate American Agriculture in National Security”. USDA.gov. July 8, 2025.

[vi] Committee for Economic Development (CED). “USDA’s Farm Security Plan Links Agriculture to National Security”. The Conference Board (TCB). July 23, 2025.

[vii] Zynda, Haley. “The History of American Agriculture”. The Ohio State University. July 4, 2022.

[ix] USDA. “Nutrition Programs”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[x] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: Farm Safety Net Programs”. Congressional Research Service (CRS). September 22, 2022.

[xi] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: Federal Crop Insurance Program”. CRS. August 26, 2022.

[xii] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[xiii] USDA Economic Research Service. “Risk Management – Crop Insurance at a Glance”. ERS.USDA.gov. September 23, 2025.

[xiv] USDA Economic Research Service. “Risk Management – Crop Insurance at a Glance”. ERS.USDA.gov. September 23, 2025.

[xv] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: Federal Crop Insurance Program”. CRS. August 26, 2022.

[xvi] Whitt, Christine. “Farm Bill Primer: Disaster Assistance”. CRS. January 22, 2025.

[xvii] Whitt, Christine. “Farm Bill Primer: Disaster Assistance”. CRS. January 22, 2025.

[xviii] Whitt, Christine. “Farm Bill Primer: Disaster Assistance”. CRS. January 22, 2025.

[xix] USDA Economic Research Service. “Farm & Commodity Policy – Title I: Crop Commodity Program Provisions”. ERS.USDA.gov. January 8, 2025.

[xx] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: PLC and ARC Farm Support Programs”. CRS. May 16, 2022.

[xxi] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[xxii] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: PLC and ARC Farm Support Programs”. CRS. May 16, 2022.

[xxiii] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: PLC and ARC Farm Support Programs”. CRS. May 16, 2022.

[xxiv] Farmdoc. “Estimates of 2024 ARC-CO and PLC Payments”. Successful Farming. November 12, 2025

[xxv] USDA Farm Service Agency. “Emergency Commodity Assistance Program (ECAP)”. FSA.USDA.gov. 2025.

[xxvi] USDA Farm Service Agency. “2023/2024 Supplemental Disaster Assistance”. FSA.USDA.gov. 2025.

[xxvii] USDA Economic Research Service. “Farm & Commodity Policy – Title I: Crop Commodity Program Provisions”. ERS.USDA.gov. January 8, 2025.

[xxviii] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: MAL and LDP Farm Support Programs”. CRS. June 22, 2022.

[xxix] Rosch, Stephanie. “Farm Bill Primer: MAL and LDP Farm Support Programs”. CRS. June 22, 2022.

[xxx] Greene, Joel L. and Whitt, Christine. “Farm Bill Primer: Support for the Dairy Industry”. CRS. January 29, 2025.

[xxxi] USDA. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program”. USDA.gov. December 2018.

[xxxii] Aussenberg, Randy Alison and Billings, Kara Clifford. “Farm Bill Primer: SNAP and Nutrition Title Programs”. CRS. January 7, 2025.

[xxxiii] Aussenberg, Randy Alison and Billings, Kara Clifford. “Farm Bill Primer: SNAP and Nutrition Title Programs”. CRS. January 7, 2025.

[xxxiv] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “TEFAP Factsheet”. FNS.USDA.gov. October 30, 2024.

[xxxv] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “CSFP Factsheet”. FNS.USDA.gov. October 30, 2024.

[xxxvi] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[xxxvii] Jones, Jordan W. “Total spending on USDA’s food and nutrition assistance programs continued to fall in fiscal year 2024”. ERS.USDA.gov. July 24, 2025.

[xxxviii] Aussenberg, Randy Alison and Falk, Gene. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits”. CRS. September 29, 2025.

[xxxix] Aussenberg, Randy Alison and Billings, Kara Clifford. “Farm Bill Primer: SNAP and Nutrition Title Programs”. CRS. January 7, 2025.

[xl] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “WIC: USDA's Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children”. FNS.USDA.gov. November 24, 2025.

[xli] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “WIC Eligibility”. FNS.USDA.gov. November 24, 2025.

[xlii] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “WIC Eligibility”. FNS.USDA.gov. November 24, 2025.

[xliii] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “WIC Benefits”. FNS.USDA.gov. November 24, 2025.

[xliv] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “Meals for Schools and Child Care”. FNS.USDA.gov. March 28, 2025.

[xlv] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “National School Lunch Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. December 11, 2025.

[xlvi] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “FNS-101: National School Lunch Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. March 4, 2021.

[xlvii] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “FNS-101: National School Lunch Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. March 4, 2021.

[xlviii] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “School Breakfast Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. March 10, 2025.

[l] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “Child and Adult Care Food Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. December 23, 2024.

[li] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program”. FNS.USDA.gov. June 24, 2025.

[lii] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[liii] Binzen Fuller, Kate. “Conservation Programs”. ERS.USDA.gov. April 22, 2025.

[liv] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lv] Binzen Fuller, Kate. “Conservation Programs”. ERS.USDA.gov. April 22, 2025.

[lvi] USDA. “Food Safety”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[lvii] 119th Congress. “H.R.1 - An act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H. Con. Res. 14.” Congress.gov. July 4, 2025.

[lviii] CED. “Senate Passes Reconciliation Bill”. TCB. July 2, 2025.

[lix] CED. “Agriculture and Nutrition Provisions in Senate Tax Bill”. TCB. July 2, 2025.

[lx] Rosenbaum, Dottie and Bergh, Katie. “SNAP Includes Extensive Payment Accuracy System”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. June 21, 2024.

[lxi] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “SNAP Payment Error Rates”. FNS.USDA.gov. June 30, 2025.

[lxii] Morris, Steve. “Farm Programs: USDA Financial Assistance to Agricultural Producers for Fiscal Years 2019–2023”. U.S. Government Accountability Office. December 17, 2024.

[lxiii] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “Nutrition Programs: Assistance for People of All Ages”. FNS.USDA.gov. 2025.

[lxiv] Jones, Jordan W. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) - Key Statistics and Research”. ERS.USDA.gov. July 24, 2025.

[lxv] Jones, Jordan W. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) - Key Statistics and Research”. ERS.USDA.gov. July 24, 2025.

[lxvi] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “Fiscal Year 2023 USDA Nutrition Education Coordination Report to Congress”. FNS.USDA.gov. March 03, 2025.

[lxvii] Saied Toossi, Jessica E. Todd, Joanne Guthrie and Michael Ollinger. “USDA’s National School Lunch Program served about 241 billion lunches from fiscal years 1969 through 2023”. ERS.USDA.gov. October 9, 2025.

[lxviii] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lxix] CED. “2024 Farm Bill: Prospects for Passage”. TCB. May 24, 2024.

[lxx] Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Budget Dynamics”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lxxi] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lxxii] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lxxiii] Johnson, Renee and Monke, Jim. “Farm Bill Primer: Background and Status”. CRS. December 27, 2024.

[lxxiv] USDA. “FY 2025 Budget Summary”. USDA.gov. 2025.

[lxxv] Congressional Budget Office (CBO). “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035”. CBO.gov. January 2025.

[lxxvi] U.S. Treasury Department. “Debt to the Penny”. FiscalData.Treasury.gov. December 15, 2025.

[lxxvii] CBO. “Monthly Budget Review: Summary for Fiscal Year 2025”. CBO.gov. November 10, 2025.

[lxxviii] CED. “Explainer: US National Debt”. TCB. August 5, 2025.

[lxxix] CBO. “Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2025 to 2034”. CBO.gov. December 12, 2024.

[lxxx] CBO. “Reduce Subsidies in the Crop Insurance Program”. CBO.gov. December 12, 2024.

[lxxxi] Goodwin, Barry K. and Smith, Vincent H. “Changes for Agriculture in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act”. AEI. October 15, 2025.

[lxxxii] Edwards, Chris. “The Farm Bill Offers an Opportunity to Reform Costly Subsidies”. Cato Institute. August 24, 2023.

[lxxxiii] Morris, Steve. “Farm Programs: USDA Financial Assistance to Agricultural Producers for Fiscal Years 2019–2023”. U.S. Government Accountability Office. December 17, 2024.

[lxxxiv] Schwab, Danielle. “Are U.S. Farms Feeding the U.S.?” Illuminate Food. March 2, 2025.

[lxxxv] CBO. “Eliminate Subsidies for Certain Meals in the National School Lunch, School Breakfast, and Child and Adult Care Food Programs”. CBO.gov. December 12, 2024.

[lxxxvi] Bland, Megan and Kallins, Lauren. “How the Federal Reconciliation Bill Will Affect Farms and Food Policy”. NCSL. 2025.

[lxxxvii] Governor Josh Stein et al. “Governors’ Letter to Congressional Leadership Re: SNAP”. June 24, 2025.

[lxxxviii] CBO. “Re: Potential Effects on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program of Reconciliation Recommendations Pursuant to H. Con. Res. 14, as Ordered Reported by the House Committee on Agriculture on May 12, 2025”. CBO.gov. May 22, 2025.

[lxxxix] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “MAHA Commission Unveils Sweeping Strategy to Make Our Children Healthy Again”. FNS.USDA.gov. September 9, 2025.

[xc] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. “SNAP Healthy Incentives”. FNS.USDA.gov. September 17, 2025.

[xci] Senator Cory Booker. “Booker, Marshall, Smith, Cassidy Urge CMS to Advance Access to Medically Tailored Meals.” September 12, 2025.

[xcii] USDA Office of Inspector General. “2025 USDA Top Management Challenges”. USDAOIG.Oversight.gov. September 30, 2025.

[xciii] USDA Office of Inspector General. “Office of Inspector General Semiannual Report to Congress FY 2025 - First Half”. USDAOIG.Oversight.gov. June 2, 2025.

[xciv] USDA Office of Inspector General. “FNS SNAP: Disbursement of SNAP Benefits Using the EBT System”. USDAOIG.Oversight.gov. April 14, 2025.

[xcv] USDA Office of Inspector General. “Food and Nutrition Service’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Fraud Risk Assessments”. USDAOIG.Oversight.gov. May 29, 2025.

President

Committee for Economic Development, the public policy center of The Conference Board (CED)

Head of Public Policy & Research, CED

Committee for Economic Development, the public policy center of The Conference Board (CED)

Researcher and Writer, Fiscal Policy

Committee for Economic Development, the public policy center of The Conference Board (CED)