To tackle the growing national debt and ensure the solvency of Social Security and Medicare, a bipartisan fiscal commission in Congress is a promising solution.

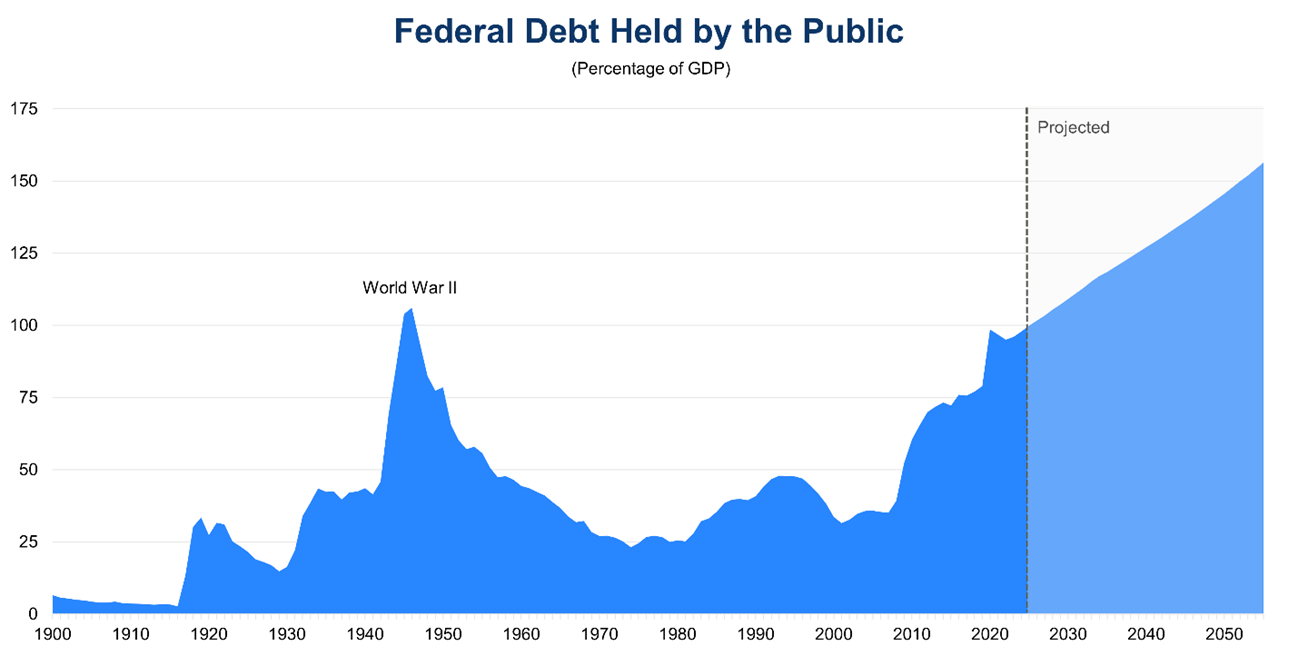

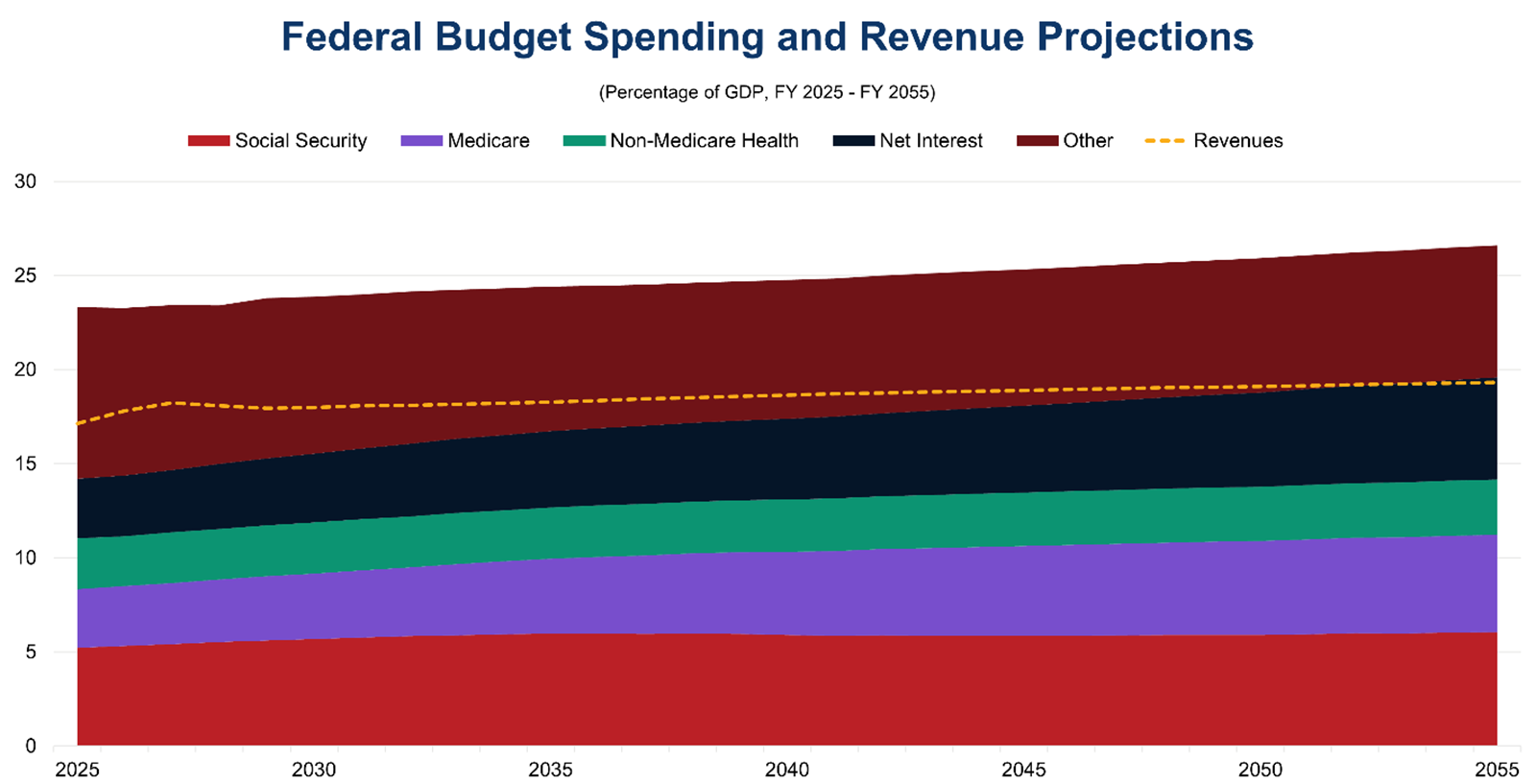

learn moreTo tackle the United States’ rising national debt (currently exceeding $38 trillion) and ensure the solvency of the primary Trust Funds for Social Security and Medicare, establishing a bipartisan fiscal commission in Congress, composed solely of Members of Congress, to tackle deficits, spending, and the national debt is a promising solution that could break the political impasse surrounding this issue and restore Congressional powers that have eroded over time. To establish a bipartisan fiscal commission, policymakers should consider the following: The national debt is the amount of money the Federal government has borrowed to cover the outstanding balance of expenses incurred over time.1 The national debt is currently over $38 trillion and rose over $2 trillion in 2025.2 Government spending also exceeded revenues by $1.8 trillion in fiscal year (FY) 2025, with spending on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and net interest on the national debt increasing by 8% compared to FY2024.3 Combined with rising costs to service the national debt and the impending insolvency of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds over the next decade, the US faces a strongly negative fiscal outlook that, absent immediate action from Federal policymakers, will only continue to worsen.4 Figure 1: Federal Debt Held by the Public as a Percentage of GDP (1900-2055) Sources: The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, January 2025; The Conference Board, 2026. Several demographic and economic trends are negatively affecting the long-term outlook for the debt. An aging population, rising health care costs, rising costs of servicing the debt, and lower economic growth and government revenues are all forces that Congress must contend with when addressing the Nation’s fiscal outlook.5 The outsized and unsustainable national debt poses significant challenges to the Federal government, US economy, and society at large—and the costs of inaction are only rising. Fundamentally, high levels of debt increase the cost of servicing the debt, which crowds out other governmental spending priorities.6 If interest rates are elevated at any point, the effect is magnified, as this requires a greater portion of revenues to be used for servicing the debt, forcing a choice between reducing discretionary spending or borrowing even more money—at higher rates—to cover that spending. Figure 2: Health Care Spending and the Cost of Servicing the National Debt Drive Increasing Deficits Over the Next Three Decades Sources: The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, January 2025; The Conference Board, 2026. As the debt continues its unsustainable path, financial markets and lenders will lose confidence in the US’ ability to pay it back, especially given long-term demographic and economic trends associated with the status quo. This has multiple effects, particularly on the government’s credit rating, higher interest rates that the Treasury must pay investors to compensate for the greater risk of default, and the value of the US dollar as investors seek safer investments. Higher interest rates could even create a “spiral” or “feedback loop” in which the cost of servicing the debt increases, leading to higher interest rates and further costs to service the debt.7 These effects reduce private investment as financial markets redirect capital to purchasing US debt and rising interest rates make it more difficult for the private sector to obtain capital. Additionally, the government will have to contend with reduced flexibility to address geopolitical events and shocks that can happen at any time, such as national security crises or major disasters. Combined with a loss of confidence in the Federal government’s ability to pay back the debt, confidence in the dollar could weaken, further inhibiting economic growth and driving inflation rates higher.8 Further, while it might once have been possible to argue that the US could simply grow its way out of debt, lower projected growth removes this excuse for inaction and forces the urgency of addressing the debt. Economic growth alone will not address structural challenges in the budget. The Conference Board forecasts that US growth is expected to slow for the remainder of the 2020s and the 2030s—the very period when the debt is projected to rise significantly—due to demographic headwinds and higher structural interest rates.9 All Americans will feel the effects of these hardships. Current retirees and those approaching retirement age (especially those with limited pensions and retirement savings) will be at risk of losing crucial income, health, and long-term care support. Younger generations will also have to bear the burden of paying off the national debt with less fiscal flexibility to address long-term, structural challenges. In short, the high national debt prevents us from investing fully in America’s future. Given the inexorable rise of the national debt over the past 25 years and Congress’s inability to address it to this point through the traditional budget process, a bipartisan fiscal commission provides a new venue to tackle the Nation’s long-term fiscal sustainability. This commission would consist of a core group of Members of Congress, assisted by outside experts, to focus solely on broad solutions to the Nation’s fiscal challenges, giving space for compromise and political cover for Congress to take the difficult votes necessary to reset our fiscal trajectory. A commission also recognizes the current budget process is broken, allows for comprehensive solutions that include action on mandatory spending and revenues, and provides an opportunity to raise public awareness and support—without which success is unlikely. Both business and voters support the concept of a bipartisan fiscal commission. A CED survey of CED Trustee CEOs and Board Directors from September 2023 found that 87% of respondents believe a bipartisan congressional commission on fiscal responsibility could help reduce the national debt.10 A survey of voters from that same year found that 68% of voters, including 69% of Democrats and 67% of Republicans, support a fiscal commission process to recommend a comprehensive package of reforms to reduce our national debt, and only 5% of all voters are opposed.11 The support of business and voters is crucial to give the bipartisan fiscal commission a mandate and demonstrates the desire for comprehensive solutions to address the Federal government’s unsustainable fiscal outlook with urgency and finality. Past commissions have addressed controversial policy issues with a significant fiscal impact. Analyzing the best practices and lessons learned from these commissions informs the design of an ideal bipartisan fiscal commission with conditions designed to promote its ultimate success. In the early 1980s, Social Security’s main Trust Fund was approaching insolvency as the costs of Social Security benefits exceeded payroll tax revenues funding the program, requiring either an automatic benefit cut or transfers from the General Fund once the Trust Fund balance was depleted. Recognizing the impending crisis, in September 1981, President Ronald Reagan appointed a 15-member bipartisan National Commission on Social Security Reform chaired by Alan Greenspan, former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors. The President, Speaker of the House Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill (a Democrat), and Senate Majority Leader Howard Baker (a Republican) chose the members, of whom nine were current or former Members of Congress. The Commission also included outside experts and representatives from labor and business.12 The President tasked the “Greenspan Commission” with delivering a report by the end of 1982 on solutions to address the impending insolvency of the Social Security Trust Fund.13 After a year of deliberations, the Greenspan Commission remained deadlocked. In January 1983, a smaller sub-group comprising Senators Daniel P. Moynihan and Robert Dole, Robert Ball (former Social Security Commissioner), and Representative Barber Conable (ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee) began discussions with White House Chief of Staff James A. Baker III on a potential legislative deal. These proxy negotiations between President Reagan, Speaker O’Neill, and key Senators led to a compromise package of revenue, benefit, and eligibility changes that the full Greenspan Commission ultimately endorsed.14 As Congress debated the Commission’s recommendations, the Senate adopted an informal rule that any Senator who opposed the recommendations must come up with a solution of their own. In the House, Rep. J.J. Pickle, Chairman of the House Ways and Means subcommittee on Social Security, proposed a significant amendment that gradually raised the full retirement age from 65 to 67 over a period of 40 years.15 This provision and the Commission’s recommendations formed the basis of the Social Security Amendments of 1983 that extended the balance of the Social Security Trust Fund by decades and constitute the last major reform of the program.16 Crucial to the success of the legislation was a private pact between President Reagan and Speaker O’Neill not to oppose publicly the Commission’s recommendations.17 While the Greenspan Commission itself did not craft the compromise deal, the combination of the Commission’s well-respected lawmakers, outside experts, backing of Congressional and Presidential leadership, and willingness to address Social Security’s urgent fiscal challenges were important factors in the final passage of the 1983 Social Security reforms. In January 2010, the Senate debated bills to establish a commission to address the rising national debt and the Federal government’s routine annual deficits. At the time, the total national debt was approximately $13.5 trillion and the Federal budget deficit was more than $1 trillion.18 While none of the bills passed, President Barack Obama issued an Executive Order in February 2010 to establish the bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, chaired by former White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles and former Republican Senate Whip Alan Simpson.19 The “Simpson-Bowles Commission” had a goal of building bipartisan consensus to put forth solutions to tackle the Nation’s long-term fiscal challenges. The Commission also had a strategic objective of eliminating the primary budget deficit (excluding interest payments on the debt) by 2015 and reducing total deficits to 3% of GDP. The Commission consisted of 18 members. The leaders of the Senate and House appointed 12 members—three each by the Republican and Democratic leaders of both chambers—who were required to be sitting Members of Congress. The President appointed the other six members, of which no more than four could be members of the same party. Crucially, the support of a “supermajority” of 14 of the 18 Commission members was required to report recommendations to Congress by a deadline of December 1, 2010.20 Because the Commission was established by Executive Order rather than by law or Congressional resolution, it could not include fast-track protections for consideration of its recommendations in Congress, meaning that the Commission had power to generate political momentum, but not to force a vote in Congress.21 In November 2010, co-chairs Simpson and Bowles released their “Chairmen’s Mark,” a broad plan to reduce the Federal deficit through spending cuts and tax increases, as a preview of the Commission’s final report.22 This release provoked controversy from both sides of the political aisle, as liberals decried the spending cuts and conservatives criticized the proposals to raise revenues. Equally, however, the Commission aimed to ensure that the burden of deficit reduction did not fall in one area; shared responsibility was the only way forward. The Commission issued its final report on December 1, outlining proposals in six areas to meet its strategic objective.23 The report proposed a cap on discretionary spending of 21% of GDP, reductions to Federal health care spending and other mandatory expenditures, Social Security reforms, reducing tax expenditures to increase total government revenue to 21% of GDP while lowering tax rates, and various process and administrative reforms.24 The Commission also suggested waiting for two years to implement the spending cuts and tax increases to preserve the fragile economic recovery after the 2008 financial crisis. Unfortunately, only 11 of the 18 members of the Simpson-Bowles Commission supported the final recommendations, leaving it short of the supermajority to send the report to Congress for its consideration. Five of the six House appointees voted no.25 After his party suffered steep losses in the 2010 midterm elections, President Obama also distanced himself from the Commission’s recommendations. Despite its failure to reach the support necessary to submit its recommendations for Congressional consideration, the ideas that the Commission discussed would serve as a foundation for piecemeal reductions in the deficit in the early 2010s amid several rounds of fiscal negotiations tied to sequestration, a fiscal cliff in 2013, raising the debt ceiling, and associated government shutdowns.26 By 2015, Congress had enacted nearly 130% of the Commission’s recommended discretionary spending cuts, including roughly $1 trillion in savings under the Budget Control Act.27 Nevertheless, Congress’s inability to address revenues and mandatory spending—primarily Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and interest on the debt—means that US fiscal challenges have persisted and indeed worsened. The Department of Defense (DOD) began widespread closure of excess military infrastructure in the 1960s and 1970s to align with the US’s new geopolitical role during the Cold War.28 Because of their economic and employment impact on nearby communities, the future of military bases is a preeminent concern for Members of Congress that represent districts and states with these defense installations. Given this local pressure against the authority of the Secretary of Defense to close military bases, in 1977 Congress required DOD to provide 60 days’ notice of its intent to close a base and abide by any decision Congress takes to keep the base open and to conduct comprehensive assessments before reporting to Congress, which could be challenged in court on environmental or administrative grounds. Because of this legislative check, the US military did not close any bases over the next 10 years.29 In the 1980s, President Reagan was committed to cutting government spending without affecting US military readiness and geopolitical strength. Recognizing the opportunity to operate the US defense budget and US military bases more efficiently, President Reagan supported legislation that would eventually become the Base Closure and Realignment Act in 1988. The Act established an eight-member (later increased to nine members) bipartisan, independent Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission to select military bases for closure based upon recommendations from the Secretary of Defense.30 The President appointed BRAC Commission members after consulting with Congressional leadership, and all members were Senate-confirmed.31 In addition to the independent BRAC Commission, the military base closure and realignment process relied on objective and uniform criteria informed by Government Accountability Office (GAO) review and certification of DOD data; transparent deliberations with open hearings, requests for feedback, and publicly-available data; a requirement for the President and Congress to accept or reject the Commission’s recommendations in their entirety; and a property disposal process with direct local input.32 Once the BRAC Commission developed its recommendations, the Commission transmitted them to the President to decide whether to accept or reject them. If accepted, the recommendations then went to Congress with a 45-day deadline for Congress to reject them in their entirety via a joint resolution or other statutory vehicle. Otherwise, DOD began implementation of the military base closures and realignments by default.33 DOD has special accounts within the US Treasury for which Congress makes appropriations to fund the upfront costs associated with military base closure and realignment.34 The BRAC Commission process successfully closed and realigned dozens of military bases over the course of five rounds in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1995, and 2005. The local economic impact of the BRAC process and earlier base closures has been mixed. An economic analysis of military base closures between 1971 and 1994 found that employment costs were mostly limited to the direct job losses from military transfers out of the region and that per-capita income was minimally affected by the closures on average.35 Many earlier closures were in remote areas or in urban centers, and some communities sold the land and ports to developers or private companies for other uses, further minimizing the economic impact. However, some communities that relied on military bases did suffer sharp employment and business losses.36 Over the past several years, lawmakers in Congress have introduced legislation to establish a bipartisan fiscal commission. In early 2024, the Fiscal Commission Act of 2023 (H.R. 5779) passed the House Budget Committee 22-12 with bipartisan support.37 The Commission’s strategic objectives are to improve the long-term fiscal condition of the Federal government, achieve a debt-to-GDP ratio of 100% by FY2039, and improve the solvency of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. If enacted, this Commission would comprise 16 members: 12 current Members of Congress (three chosen by each leader of the Senate and House) with voting power and four nonvoting outside experts (one chosen by each leader). In the bill that passed the House Budget Committee, the Commission would focus on both mandatory and discretionary spending and revenues, hold six hearings (including field hearings and hearings to solicit expert testimony), and would have issued a report by December 2024 with recommendations and Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates of its proposals. A bipartisan majority must approve all recommendations (with at least three members from each party), which would receive expedited debate and a mandatory vote in both chambers. In order to elevate the issue with voters, the Commission would also be tasked with a public awareness and education campaign.38 In the Senate, former Senators Mitt Romney and Joe Manchin introduced companion legislation (S.3262, Fiscal Stability Act of 2023) with a similar proposal.39 The Sustainable Budget Act of 2022 (H.R. 710), co-sponsored by Representatives Ed Case (D-HI) and Steve Womack (R-AR), is another bipartisan fiscal commission proposal.40 The bill establishes a Commission to propose recommendations to balance the budget (excluding interest payments on the debt) over 10 years and to meaningfully improve the long-term fiscal outlook, including addressing the growth of entitlement spending and the gap between projected Federal revenues and expenditures. The Commission would include 18 members: three selected by the leader of each party in the House and Senate and six by the President (of whom not more than four would be from the same political party). The Commission would have a year to develop a final report, which must be supported by a supermajority of 12 members with at least four members from each political party. The President would submit the commission’s report to Congress along with a proposed joint resolution to implement the report’s recommendations, in consultation with relevant Congressional Committees, CBO, and the GAO. Congress would then consider the joint resolution under expedited procedures leading up to a mandatory vote on the legislation. For a bipartisan fiscal commission to be successful, there must be sufficient political will, strong leadership, and a spirit of collaboration. With this foundation in mind, the design of the commission itself entails describing its strategic objectives, membership, the roles of the President and outside experts (if any), procedures for Congressional approval, timelines, and administrative processes. This Brief focuses on the design of the commission itself. For a set of recommendations the commission can use as a starting point for its work, CED has released detailed solutions to address the debt crisis,41 save Social Security,42, modernize Medicare and other Federal health programs for sustainability and quality,43 and reform the budget process.44 Commissions with strong foundations work because they can break partisan logjams, focus both political parties on finding a solution, bring bipartisan credibility to reforms, and encourage public support. Commissions provide structure for negotiations and legislative procedures for enactment, but by themselves, they cannot produce the political will for reform.45 Thus, complete approval from the leadership of both parties is a necessary first step. The experience of the Simpson-Bowles Commission shows that conditional support will result in failure, especially when it comes time for difficult compromises. Establishing that commission via Executive Order also did not fully address Congress’s role.46 Conversely, the political support from President Reagan and Speaker O’Neill in the lead up to the Social Security reforms of 1983 was critical to securing a deal outside of (but certainly in the context of) the Greenspan Commission. Political leaders in Congress, and particularly the co-chairs of the commission, must demonstrate strong leadership and harness their individual strengths. Leaders must face the hard truths of our debt crisis and the difficult tradeoffs to address it. Leaders must trust that voters want the truth and understand the importance of shared sacrifice to improve our Nation’s fiscal outlook. Republicans and Democrats have different strengths on fiscal policy, with Republicans generally more trusted by voters on defense and taxes and Democrats on mandatory spending. Therefore, each party endorsing solutions in its area of strength with voters would boost the credibility of any final recommendations package.47 The commission must also embrace a genuine spirit of bipartisanship and collaboration. To do this, the commission should hold confidential discussions and members should build personal relationships, perhaps through informal dinners and social gatherings to develop rapport and understanding.48 The co-chairs of the commission must also have a strong working relationship. One strength of the Simpson-Bowles Commission was close collaboration and complementary skills of its co-chairs, who appealed to different stakeholders and sections of the public.49 Strategic objectives The commission should have strategic objectives. The three primary objectives should be to improve the long-term fiscal condition of the Federal government, reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio to a more sustainable level over the next 10 years (such as 100%), and to address the long-term solvency of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. Everything must be on the table, and the commission should undertake a top-to-bottom review of all Federal spending and revenue sources.50 While the current debt held by the public is already 100% of GDP, the trend over the next 30 years will tip today’s debt environment into an acute crisis. Additionally, the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds are projected to become insolvent within the next decade, requiring either an automatic benefit cut or transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury to backfill the program. All three objectives are necessary to address the country’s fiscal challenges comprehensively. There is a debate whether targeted commissions addressing Social Security, Medicare, or tax revenues may be more successful than one that holistically considers the entire Federal budget.51 Participants in the Simpson-Bowles Commission noted that their goal of systematic changes versus smaller objectives motivated their work and, in fact, facilitated the building of a majority (but not supermajority) coalition in support of the final recommendations.52 Our fiscal challenges are systemic and require comprehensive solutions—and piecemeal changes fail to acknowledge this reality. One potential modification could be to have parallel subcommittees for specific areas of the budget, including defense spending, non-defense discretionary spending, Medicare, Social Security, and tax policy. Before the commission can present a final package for approval, these subcommittees must ultimately align their recommendations to avoid incompatible solutions such as duplicative taxes; poor interactions between Federal programs; and putting the burden of spending cuts on specific demographic groups, notably older Americans.53 Membership For a commission to be bipartisan, both chambers of Congress and both political parties must be represented. Both the Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Sustainable Budget Act wisely note the importance of Congressional leaders in promoting ultimate success by vesting appointment power with them, increasing the chances of success (although on the Simpson-Bowles model, the Sustainable Budget Act includes members appointed by the President, though with a reduced supermajority for issuing recommendations). Membership should be selective and consensus-building skills should be prioritized. The members should also bring credibility within Congress and the public. To maximize political will in Congress, all voting members on the commission should be current Members of Congress.54 Congress has the constitutional “power of the purse,” and voting members must have the responsibility to make difficult political decisions. The Fiscal Commission Act of 2023 can serve as a model for the commission membership, with 12 voting members, three chosen by each leader in the Senate and House. Congressional leaders may choose the heads of relevant fiscal committees, such as Budget, Finance, Ways and Means, and Energy and Commerce, though this structuring risks replicating the current broken budget process. The choice of who chairs the commission is also an important consideration. In the current highly politically polarized environment, it could be difficult to find one chair who can command a broad base of support and respect across both political parties, as Alan Greenspan did in the early 1980s. To ensure a perception of fairness, the commission should have two co-chairs, one from each political party. The Congressional leaders from the Democratic and Republican parties may choose one each, but this may not produce co-chairs with a good working relationship. Thus, it makes sense for all four Congressional leaders (House Speaker, House Minority Leader, Senate Majority and Minority Leaders) to choose the co-chairs jointly.55 Outside experts It is valuable for the commission to consult with outside experts to develop recommendations and bring new voices to the conversation. These individuals may be budget experts, academics, business leaders (particularly those with experience working with the Federal government or leading transformational change), or former political leaders.56 These experts should understand retirement security and health care policy to make informed decisions on Social Security and Medicare reforms.57 Experts on emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and biomedicine, can provide valuable feedback on long-term trends that could influence the cost and efficiency of medical care and their implications for Federal health programs. They should also reflect a broad range of values, backgrounds, and interests, including representing different generations.58Again, the Fiscal Commission Act of 2023 is a good model for selecting outside experts, with one each selected by the leaders from both parties in the House and Senate for a total of four nonvoting members, who may be supplemented by other experts the Commission appoints or consults. Some analysts have advocated for a true BRAC-style commission of independent experts to develop recommendations for approval by the President and Congress.59 These analysts highlight the BRAC Commission’s success as an independent body and forcing an up or down vote on its recommendations in their entirety.60 While this truly insulates Congress from making the difficult compromises associated with the recommendations, this option hinders developing political will in Congress and reduces democratic accountability at the very time that Congress’s powers have already become weakened. The BRAC process worked in part because Congress understood that closing bases would impose losses on a few while benefiting the many. The major impediment to base closures was also local politics rather than cross-cutting political and policy issues.61 In contrast, the Federal budget is a statement of spending priorities affecting virtually every American, albeit in different ways. This requires the resolution of a host of challenges, not just local politics. Outsourcing these difficult decisions to outside experts risks the public and voters characterizing the commission as “out-of-touch elites” with no accountability. A related option is to have a BRAC-style commission of independent experts—appointed by the leaders of both parties in Congress—form their own fiscal plan to serve as a “fail-safe” in case the commission made up of Members of Congress does not agree on a plan.62 In that event, the report from the commission of outside experts would be sent for Congressional approval (in the manner described below). However, for greater credibility and likelihood of success, it would be better for Congress to come up with its own plan, to reaffirm its control of power over spending. Procedures for Congressional approval A bipartisan majority of members must approve the final plan for the commission to approve a report with recommendations. The threshold should be a simple majority, with at least three members of each party in support, as in the Fiscal Commission Act. The supermajority threshold from the Simpson-Bowles Commission of 14 of 18 members (78% support) is simply too high as Congress only needs two-thirds support to override a Presidential veto (the final Simpson-Bowles report achieved 61% support). Presumably for this reason, the Sustainable Budget Act lowers the supermajority to two-thirds. To provide members with flexibility during deliberations, in the spirit of deliberation on the Greenspan Commission’s recommendations, if members want to remove a specific recommendation from consideration, they should commit to offering a recommendation with a similar reduction in the deficit, though it is important to include the provision that the vote on the recommendations of the commission is in order and unamendable, to prevent single issues from defeating the whole report.63 Another choice to make is whether the President should have the ability to approve or reject the final recommendations package before Congress considers it. Under the BRAC framework, the President has the first pass at approving recommendations for military base closures and realignments. The commission could adopt this procedure and allow for the commission to make a counterproposal to address the President’s concerns in the event of a rejection.64 However, this risks a bottleneck that could torpedo political momentum for passage, especially given that the President will have to sign or veto the legislation that Congress passes anyway. It also undermines the concept of the mandatory vote in Congress. Thus, securing formal Presidential approval before Congress considers the final report is not necessary. To allow the commission to present the agreement it has reached without losing political momentum, the law establishing the commission should include strict timelines and commitments for votes on the House and Senate floor.65 These procedures should prevent amendments to the recommendations and force a vote on the entirety of the proposal. The approval thresholds can be a simple majority in the House and 60 votes in the Senate, in keeping with the Senate rules. If the legislation includes a back-up commission in the event the original commission remains deadlocked, the outside experts’ final recommendations would receive similar expedited consideration. A Member of Congress would have to agree to sponsor this bill. As discussed above, the Greenspan Commission succeeded in part because of a separate amendment in Congress and strong political will on both sides. But this exception proves the rule: because of the Senate’s informal rule that a Senator who opposed the recommendations must develop another solution, this separated the recommendations from regular debate. In contrast, if amendments were permitted to the fiscal commission report, it would be too easy for the recommendations to be voted down. Instead, having one complete package increases the likelihood of success through shared political responsibility in support of a solution that, even if not perfect, has at least garnered bipartisan support—an indispensable key to enactment. One reason for the long-term failure of the Simpson-Bowles Commission was the lack of fast-track procedures and no commitment for a vote in Congress. In contrast, the BRAC Commission has been successful in part because of the requirement of a vote to approve or reject the totality of its recommendations. Constitutional issues regarding Congress’s sole legislative authority almost certainly preclude adopting BRAC’s default method of beginning implementation of its approved recommendations unless Congress passes a joint resolution of disapproval within 45 days, which illustrates the need for expedited consideration and requiring votes on the package without amendment. It may be easier to enact legislation that must be rejected in its entirety rather than having individual votes on elements of a massive package of reforms that must be affirmatively supported by majorities in both chambers of Congress. Following enactment, Congress should adopt strong enforcement mechanisms for future fiscal decisions to avoid altering the new fiscal trajectory. One option is requiring “pay-go” for new spending or tax cuts to ensure they are deficit neutral.66 Any tax and spending proposal should be deficit neutral on a sufficiently long time horizon (such as 10 or 30 years) and perhaps on a dynamic basis (accounting for the economic consequences of the proposal), as determined by CBO.67 Congress may also adopt automatic stabilizers such as the “Swiss Debt Brake” to ensure future spending and revenue decisions are deficit neutral across the business cycle.68 Timeline Ideally, whenever the actual legislation for a commission is passed, the commission should be established towards the beginning of a new Congress and finish its efforts—making recommendations, expedited consideration of them, and required votes—before the next Congress is sworn in, giving the commission roughly two years to complete its work. Operating on a shorter timeframe does not provide sufficient time for a public education campaign and deliberations. Having the commission span two Congresses risks losing political momentum and belies the urgency of the moment to address the debt crisis. Divided government could facilitate the commission’s work and make any final deal durable, as it forces bipartisan compromise (instead of one party pursuing budgetary changes through reconciliation).69 Some analysts have suggested releasing the final report during the “lame duck” period between the November election and the January start of the new Congress to avoid the election subsuming the commission’s final report.70 Transparency and other administrative procedures Finally, the design must consider transparency and how the commission will operate as it develops its recommendations. In general, the commission must be a space for confidential negotiations and must not have leaks. Commission members need to have open and frank discussions without fear of reprisal from special interests.71 Nevertheless, transparency is crucial to building credibility among Members of Congress and the public. Thus, the commission should hold public hearings to gather testimony from experts and other stakeholders while commission members deliberate in private and negotiate the final recommendations. Commission members should continuously engage the public through media outreach and meetings throughout the country as part of a public education campaign (described below).72After releasing its recommendations, the commission must promote its conclusions and reforms in the public debate, before Congress considers them in mandatory votes.73 The commission’s staff are another crucial design element. Commission staff are important to engage and build trust among members, arrange testimony from witnesses, serve as informational conduits, and compile data to answer member questions.74 Commission staffing must be bipartisan and have sufficient resources to conduct analyses and support a public education campaign.75 The commission’s deliberations must also be fact-based. In interviews with participants in the Simpson-Bowles Commission, members were routinely surprised by factual presentations of the magnitude of our fiscal crisis and appreciated the frank, fact-based discussions.76 Part of this work involves agreeing on a budget baseline, a dispute that the Simpson-Bowles Commission faced when considering expiring tax cuts in the early 2010s (similar to the budget baseline disputes during the 2025 reconciliation bill debate).77 Other oversight mechanisms include publishing meeting agendas and minutes, issuing periodic reports of the commission’s progress, and facilitating public access to the commission’s documents and data.78 To inform the commission’s work and build the political will for its success, the commission must engage in a public education campaign throughout its tenure. The public must be involved, educated, and understand the consequences of inaction.79 The campaign would address the lack of political will by informing voters about the nature of the fiscal crisis, raising support for action and reducing the political cost of adopting difficult solutions, thus assisting the commission’s work in promoting solutions.80 A public education campaign also promotes honest debate. The 9/11 Commission helped raise awareness to national security vulnerabilities, and Simpson-Bowles highlighted the unsustainable long-term fiscal outlook and the need to assess all areas of the budget and tax code for solutions.81 The business community should support this campaign by both contributing potential solutions and promoting the commission’s recommendations to the public. Building grassroots support requires a nationwide campaign that also targets groups which are particularly vulnerable to the effects of a debt crisis, including younger generations, low-income communities, and the “sandwich” generation that is both concerned with education for children and retirement and health care for their parents.82 Public hearings and town halls would help to build public support. Ideally, the commission would hold events throughout the country and, of course, online. Following the failure of Simpson-Bowles, one analyst even recommended holding hearings in every state and in the top 20 major cities to demonstrate the national effects of our fiscal challenges, though this is impractical for a commission comprised by only Members of Congress. Commission members and staff must educate, engage, and empower the public through this outreach and build support networks with state and local lawmakers, reporters, finance experts, businesses, and nonprofits.83 Business leaders should be active participants in these events and encourage their employees to engage in the conversation. Social media and podcasts will be crucial to reach younger Americans and those who don’t interface with traditional news media to get their information. As younger generations will bear the burden of inaction, the national debt has generational equity implications. Thus, the commission should consider younger Americans’ voices and interests when assessing the sustainability of its recommendations, while having to balance long-term considerations with the older generations’ more immediate retirement security needs. The commission could also conduct surveys encouraging respondents to make tradeoffs and share their results. Understanding voters’ preferences when faced with budgetary tradeoffs could inform the commission’s work and build realistic expectations among the public.84 In addition to educating and engaging with the public, the campaign should also solicit ideas and suggestions from all Americans. A model for this engagement is the National Partnership for Reinventing Government, led by Vice President Al Gore in the 1990s.85 The Administration directed agencies to set up “reinvention laboratories” within each agency to pilot innovations in service delivery accompanied by waivers from internal agency rules. In 1993, Vice President Gore participated in town hall meetings with agencies to hear firsthand from Federal workers on what could be improved and hosted a summit with business leaders and operational experts to learn from the private sector. Following the report, the President and Vice President embarked on a tour of the country to promote their efforts.86 The bipartisan fiscal commission could employ a similar engagement campaign, this time targeting the public and businesses, and harnessing social media to build sustainable, broad-based support for the commission’s work. Business leaders have a crucial role to play in providing ideas and perspective from the private sector. The public’s engagement is also crucial to engage lawmakers and make addressing our fiscal crisis a priority issue for voters. The debt crisis is already here. If left unaddressed, it will only continue to worsen, demanding policymakers’ and the public’s urgent attention. Forming a bipartisan fiscal commission is the first step in developing a comprehensive plan to address the national debt and to facilitate Congress taking action, in order to begin turning the tide on the rising national debt and preserve our national prosperity for future generations. 1. Explainer: US National Debt, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, August 2025. 2. US Treasury Department, Debt to the Penny, January 14, 2026. 3. Congressional Budget Office, Monthly Budget Review: September 2025, October 8, 2025. 4. Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees Release Annual Trust Fund Report, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, June 2025. 5. Explainer: US National Debt, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, August 2025. 6. Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, February 2023. 7. Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, February 2023. 8. Explainer: US National Debt, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, August 2025. 9. Global Economic Outlook 2026: US Edition: Transformation Amid Slower Growth, Economy, Strategy & Finance Center, The Conference Board, December 2025. 10. Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray, The Debt Crisis is Here, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 13, 2023. 11. Poll: Strong Bipartisan Majority of Voters Call for Fiscal Commission, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, September 25, 2023. 12. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 13. Rudolph G. Penner, The Greenspan Commission and the Social Security Reforms of 1983, The Urban Institute, 2013. 14. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 15. Rudolph G. Penner, The Greenspan Commission and the Social Security Reforms of 1983, The Urban Institute, 2013. 16. Office of Legislation & Congressional Affairs, Summary of P.L. 98-21, (H.R. 1900), Social Security Amendments of 1983-Signed on April 20, 1983, Social Security Administration, November 26, 1984. 17. Brian Reidl, Yes, Fiscal Commissions Can Succeed With a Committed Congress, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 18. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 19. The White House Office of the Press Secretary, President Obama Establishes Bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, Obama White House Archives, February 18, 2010. 20. The White House Office of the Press Secretary, President Obama Establishes Bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, Obama White House Archives, February 18, 2010. 21. James C. Capretta and Jack Rowing, A Look Back at Simpson-Bowles, American Enterprise Institute, November 29, 2023. 22. Tax Policy Center, The Bowles-Simpson ‘Chairmen’s Mark’ Deficit Reduction Plan, November 12, 2010. 23. The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, The Moment of Truth, The White House, December 2010. 24. Kimberly Amadeo, Simpson-Bowles Plan Summary, History, and Whether It Would Work, The Balance, February 21, 2021. 25. James C. Capretta and Jack Rowing, A Look Back at Simpson-Bowles, American Enterprise Institute, November 29, 2023. 26. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Five Years Since Simpson-Bowles: How Much of It Have We Enacted?, December 3, 2015. 27. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 28. Andrew Tilghman, Excess Military Infrastructure and the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Process, Congressional Research Service, May 27, 2025. 29. Steven J. Ramold, BRAC Commission Is Established to Close U.S. Military Bases, EBSCO, 2023. 30. Steven J. Ramold, BRAC Commission Is Established to Close U.S. Military Bases, EBSCO, 2023. 31. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool To Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 32. Andrew Tilghman, Excess Military Infrastructure and the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Process, Congressional Research Service, May 27, 2025. 33. Andrew Tilghman, Excess Military Infrastructure and the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Process, Congressional Research Service, May 27, 2025. 34. Department of Defense, DoD Base Realignment and Closure, April 2022. 35. Mark A. Hooker and Michael M. Knetter, Measuring the Economic Effects of Military Base Closures, National Bureau of Economic Research, February 1999. 36. Steven J. Ramold, BRAC Commission Is Established to Close U.S. Military Bases, EBSCO, 2023. 37. Representative Bill Huizenga, H.R. 5779 – Fiscal Commission Act of 2023, US Congress, January 2024. 38. Congressional Fiscal Commission Proposal, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, January 25, 2024. 39. Senator Joe Manchin, S.3262 - Fiscal Stability Act of 2023, US Congress, November 2023. 40. Representative Ed Case, H.R.710 - Sustainable Budget Act of 2022, US Congress, November 2023. 41. Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, February 2023. 42. Saving Social Security, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, February 12, 2024. 43. Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, November 18, 2024. 44. Reforming the Broken Federal Budget Process, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, February 24, 2025. 45. Brian Reidl, Yes, Fiscal Commissions Can Succeed With a Committed Congress, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 46. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 47. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 48. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 49. Ben Ritz, Setting Up a Fiscal Commission for Success, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 50. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 51. G. William Hoagland, Fiscal Commissions: Promises and Disappointments, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 52. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 53. Brian Reidl, Yes, Fiscal Commissions Can Succeed With a Committed Congress, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 54. Brian Reidl, Yes, Fiscal Commissions Can Succeed With a Committed Congress, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 55. Ben Ritz, Setting Up a Fiscal Commission for Success, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 56. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 57. Romina Boccia, Designing a BRAC-Like Fiscal Commission to Stabilize the Debt, Cato Institute, May 8, 2023. 58. Sita Slavov, Making Tough Fiscal Choices to Protect Future Generations, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 59. Romina Boccia, Designing a BRAC-Like Fiscal Commission to Stabilize the Debt, Cato Institute, May 8, 2023. 60. Dorothy Robyn, Speaker McCarthy: We Need a BRAC Commission, But Not to Tackle Federal Spending, Brookings, June 6, 2023. 61. Dorothy Robyn, Speaker McCarthy: We Need a BRAC Commission, But Not to Tackle Federal Spending, Brookings, June 6, 2023. 62. Romina Boccia, A Fail-Safe Congressional Fiscal Commission to Fix Government Spending and Debt, Cato Institute. November 29, 2023. 63. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 64. Romina Boccia, Designing a BRAC-Like Fiscal Commission to Stabilize the Debt, Cato Institute, May 8, 2023. 65. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 66. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 67. Mark Zandi, A Way to Brighten America’s Dark Fiscal Outlook, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 68. How the Swiss Debt Brake Can Improve the US Debt Ceiling, Committee for Economic Development, The Conference Board, August 11, 2025. 69. Ben Ritz, Setting Up a Fiscal Commission for Success, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 70. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 71. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 72. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 73. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 74. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 75. Rob Portman, A Bipartisan Tool to Improve America’s Fiscal Future, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 76. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 77. James C. Capretta and Jack Rowing, A Look Back at Simpson-Bowles, American Enterprise Institute, November 29, 2023. 78. Romina Boccia, Designing a BRAC-Like Fiscal Commission to Stabilize the Debt, Cato Institute, May 8, 2023. 79. G. William Hoagland, Fiscal Commissions: Promises and Disappointments, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 80. Heidi Heitkamp, To Get Our Fiscal House in Order: Put Politics First, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 81. Leon E. Panetta, Our National Debt: The Choice Between Leadership or Crisis, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 82. Heidi Heitkamp, To Get Our Fiscal House in Order: Put Politics First, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, November 2023. 83. Darrell M. West and Ashley Gabriele, Ten Leadership Lessons from Simpson-Bowles, Governance Studies at Brookings, November 2012. 84. Sita Slavov, Making Tough Fiscal Choices to Protect Future Generations, Peter G. Peterson Foundation. November 2023. 85. Charles S. Clark, Reinventing Government -- Two Decades Later, Government Executive, April 26, 2013. 86. John Kamensky, National Partnership for Reinventing Government (formerly the National Performance Review): A Brief History, National Partnership for Reinventing Government Archive. January 1999.

Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Policy Recommendations

Why Is the National Debt a Problem?

Why Do We Need a Bipartisan Fiscal Commission?

Successes and Lessons Learned from Previous Commissions

Greenspan Commission

Simpson-Bowles Commission

Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC)

Recent Congressional proposals

How to Design a Bipartisan Fiscal Commission

Foundation for success

Key design elements

Public Education Campaign

The Work Begins Now

250 Years Forward

January 20, 2026

250 Years Forward: Strengthening an American Future

January 20, 2026

Navigating the Health Care Landscape in 2026

December 01, 2025

US Lead in Public R&D Is Eroding

October 20, 2025