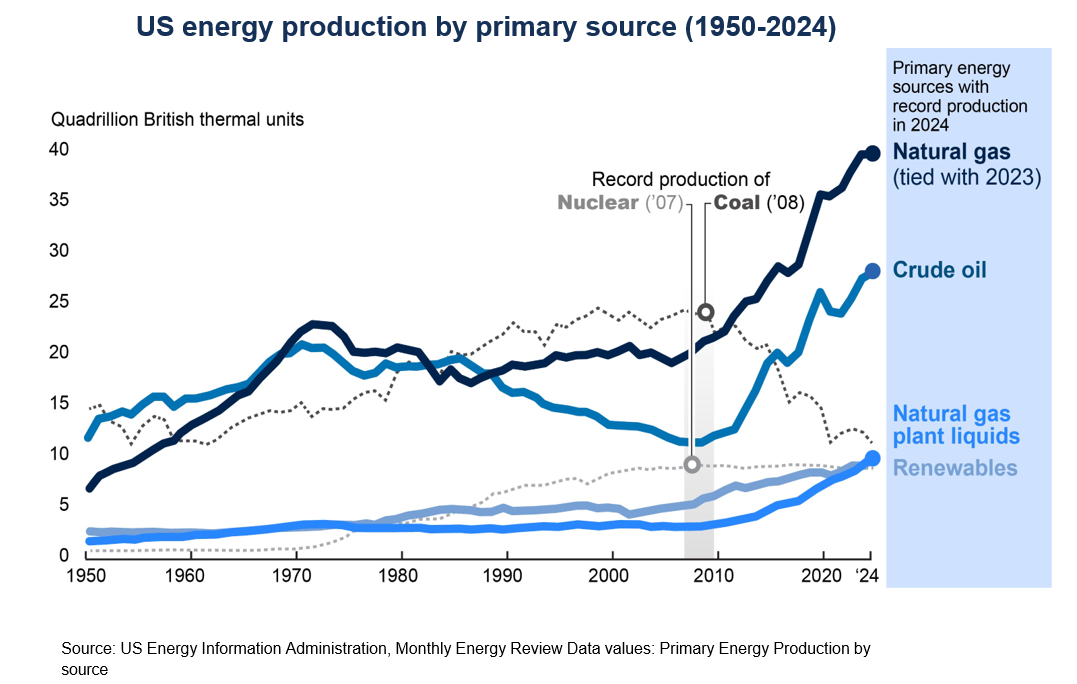

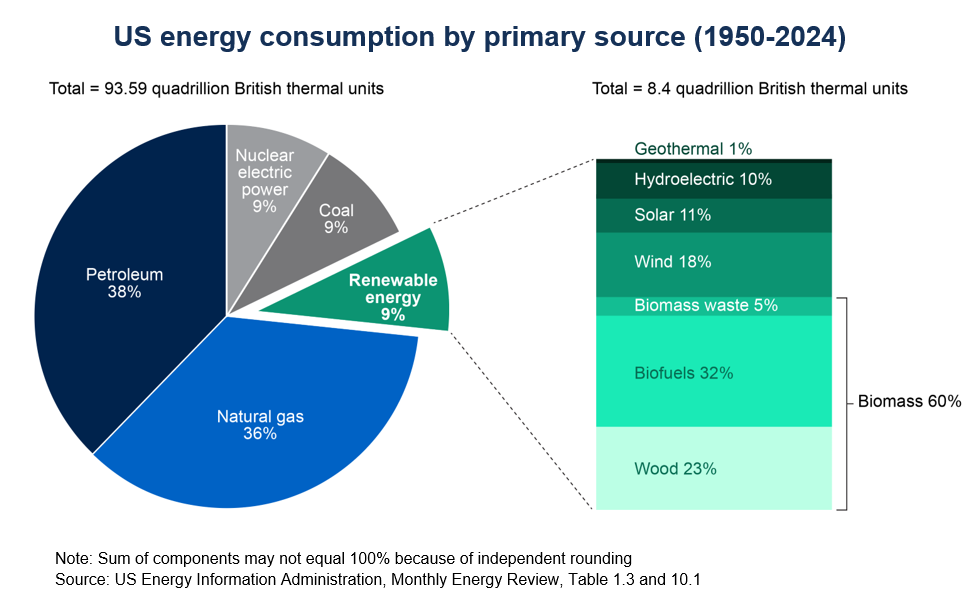

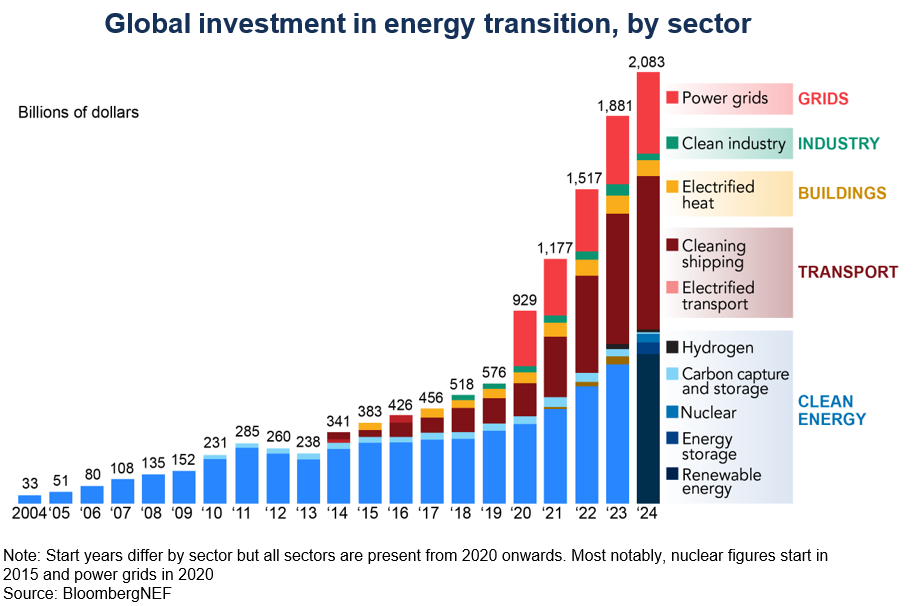

In 2019, the US became a net total exporter of energy, and energy exports rose in 2023 to their highest recorded level, approximately 29.50 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu); additionally, both 2023 and 2024 were record years for US oil production. Similarly, US energy imports peaked in 2007. These trends mean that the US has achieved the long-desired goal of energy independence. Now, the goal for energy policy is different: to sustain these trends in two senses. First, in US energy production and exports and second, in encouraging an energy mix that benefits the entire economy and all regions of the country, which will require a variety of both fossil fuels and renewable, zero carbon sources. Energy resilience, energy efficiency, and energy transmission (etting energy to users) are also equal, if not more important, goals of US energy policy. To sustain US energy independence and promote energy transmission and energy resilience, policymakers and business leaders should recognize that: The US became a net total exporter of energy in 2019, and energy exports rose in 2023 to their highest recorded level, approximately 29.50 quadrillion British thermal units. Similarly, US energy imports peaked in 2007. These trends mean that the US has achieved the long-desired goal of energy independence. Now, the goal of US energy policy is different: to sustain these trends in two senses. First, in terms of US energy production and exports and second, in encouraging an energy mix that benefits the entire economy and all regions of the country, which will require use of sustainable energy sources as well as fossil fuels. For business the stakes are high; while most businesses benefit from lower and stable energy prices, many companies have also adopted sustainability in this second sense (in energy and other aspects of business operation) as a core part of their business strategy. For these companies, energy resilience is equally, if not more, important than the broad fact of energy independence. Energy independence and increasing energy resilience put the US in a strong position, promoting economic growth. Affordability, accessibility, and reliability of supplies are also key goals for US energy policy. “Energy independence” has been a goal of US policy, with varying degrees of emphasis, at least since the 1973 oil embargo brought home the reality of a major shift towards reliance on imported oil—which peaked in 2005 at nearly 60% of US oil consumption. In reality, the last time the US enjoyed a similar sustained period of energy independence was in the 1950s. However, energy independence does not mean that the US should never import a Btu of energy. There are times when importing energy, either in the form of fuel or electricity, makes sense; for instance, importing crude oil, natural gas, and electricity (some from hydropower) from Canada, even as the US also exports energy to Canada. This does not compromise US energy independence. Rather, it builds strong markets; in particular, developing North American energy markets helps all three USMCA countries. Instead, US energy independence rests on a foundation of an adequate production base and diversity in the supply mix. Where trade in energy works well, it should not be restricted. It permits increased US exports—particularly of liquefied natural gas—which brings geopolitical benefits to the US and our allies in Europe and Asia and reduces global dependence on coal, helping other countries meet their emissions reductions targets and enjoy a cleaner environment. (As US LNG exports have risen, US coal exports have remained somewhat steady even as US coal production continues to fall.) The US is already the world’s largest exporter of LNG (11.9 billion cubic feet per day in 2024), and LNG is a growing market as many nations seek to shift away from coal. US exports are expected to grow to 200,000,000 metric tons by 2030. Expanding exports of US LNG is a relatively quick way for many countries in Europe and Asia facing higher tariffs to expand purchases of US goods and thus reduce the trade deficit, and some countries have promised to increase purchases of US energy as part of framework tariff deals. But LNG is a globally competitive market, with countries including Qatar, Australia, Russia, Malaysia, Algeria, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan also significant suppliers in the global market, and the US can generally not control how buyers act in the market and deliver gas. How can the US differentiate itself in this competitive market? Beyond using tariffs, highlight the advantages of purchasing cleaner US gas (which employs cleaner production methods), longer-term contracts, direct purchases, or direct investments in US LNG projects. These types of longer-term investments might have greater advantages for both the US and countries investing here, as some countries may not wish to depend upon the US for energy supplies. All this makes a second era of US dominance of global energy markets highly unlikely, even as the US increases energy exports. It also focuses attention on another critical issue: US leadership in clean energy technology, including exports of US clean energy products manufactured here. But this, by definition, while good for US exports, also implies that other countries will produce much of their own, likely renewable, energy. The US can compete well in these markets if US businesses are given the chance to do so. At the same time, many companies, both in the US and abroad, are pushing ahead with net zero commitments and a focus on sustainability. Sometimes this arises from the need to address concerns from investors, particularly in Europe, as well as consumers. In this context, it is also important to recognize that other nations have made decisions in favor of growing (and in some cases such as China, sharply) their use of renewable sources (as well as nuclear power and, in some cases, hydrogen) among other zero carbon options. Renewables already account for over 13% of global final energy consumption (rising to nearly 20% by 2030), with the growth in electricity even stronger, from 30% in 2023 to an expected 46% by 2030. Electricity production highlights both the importance of renewable sources as well as the challenges. The growth of AI will sharply increase demand for electricity (possibly to as much as 22% of US household consumption), putting further burden on the US to scale up, including electricity generated from all sources. However, not all this demand can or should be met with fossil fuels. In short, renewable sources of energy are an important part of energy independence. By definition, solar and wind resources available on land and in offshore waters are developed in the US—and thus contribute to sustaining energy independence. They are also sustainable sources for continued energy independence, offering benefits to businesses and consumers alike. Falling costs of power generation with renewables, including wind and solar energy, and advances in battery storage and technology—some led by US businesses—make an increased use of renewables a practical and efficient choice in many situations. Renewables already account for 21.4% of US electricity production. If renewables continue to fall in price and rise in reliability, they will gain market share provided that markets are allowed to work as they should. Zero carbon sources of energy, of course, include nuclear power. The Administration has taken steps to promote nuclear; the goal should be nothing less than a nuclear renaissance offering a stable, zero carbon base load for power grids (particularly those that increasingly rely upon more intermittent renewable sources) and industrial uses. As AI data center growth raises demand for electricity, businesses including Meta and Microsoft have responded with agreements to use nuclear power to support data centers. Nuclear power holds real promise for meeting the vastly expanded energy needs that new information technologies require. China, notably, is proposing to build 150 nuclear plants by 2030 and has approved 10 this year. A number of European countries are also expanding their nuclear programs as well, noting the role of nuclear in reaching net zero goals. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), which are cheaper to build and operate, along with other newer designs, are at the heart of the future of US nuclear power. SMRs have strict safety features, including automatic power down if safety issues occur. In 2023, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission certified the United States’ first SMR, with up to 12 modules two-thirds smaller than conventional reactors. Work now moves towards financing and quicker siting and permitting. While energy production has often been a highly regulated sector, it is important to understand the power of markets in driving both the energy independence the US has achieved and efforts to continue sustainable energy independence. Markets—and businesses—respond to incentives, whether those be in the form of tax credits, public and private research funding, deregulation, or new opportunities for development, sales, or export. This fundamental point stands whether the US has a formal goal of reaching net zero emissions or not. As CED has written: “A comprehensive and resilient US strategy must build on the foundation of market principles, accelerate innovation, and preserve US competitiveness in the global economy.” This requires policymakers and the business community to work together; it also means that government should seek to interfere with or skew markets as little as possible. Equally, regulation should be based on sound science, promote fair competition, and reviewed regularly to determine whether regulation is achieving its goals. In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided up to $384 billion related to climate and energy. Most of this (an estimated $271 billion) is in the form of tax credits for cleaner energy production. In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) included $75 billion for climate and $22 billion for environmental remediation and environmental justice provisions, as well as provisions to strengthen the power grid, an electric vehicle (EV) charging network, energy storage, and advanced nuclear reactor demonstration projects. Tax credits incentivize companies to use them. For instance, the cost to produce green hydrogen fell dramatically because of the IRA. But the most economically efficient use of these types of credits is when companies make further innovations to bring new technologies to scale and thereby determine whether technologies are economically sustainable. If they are, then costs should fall (as happened with battery packs for electric vehicles), building demand and making their rapid adoption more likely and economic. If they are not, government and markets should act to favor other technologies that can be profitable at scale. The recently enacted H.R.1, which the Administration terms the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA), makes significant changes to the tax credits enacted as part of the IRA, while preserving and expanding tax credits related to fossil fuels. Beyond eliminating or phasing out the tax credits for purchase of a qualifying electric vehicle, the residential clean energy credit (30% of the cost of the clean energy property), and the energy efficient commercial building deduction, and delaying the methane fee for 10 years, the bill sharply restricted support for wind and solar power unless a facility is placed in service by 2027—an ambitious timetable—and adds a new excise tax on wind (up to 50%) and solar (up to 30%) projects that include certain levels of materials sourced from prohibited foreign entities, depending on when construction begins and when a project comes into service. The law also expands Federal lands and waters that are open for exploration and production of oil and gas while reducing Federal royalties from production and introduces a new tax credit for metallurgical coal production, commonly used for steel, through the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit at 2.5%. After enactment of OBBBA, the President then further restricted the use of the solar and wind tax credits of the IRA by Executive Order, denying “the use of broad safe harbors unless a substantial portion of a subject facility has been built” and ordering the Treasury Department to prevent “the artificial acceleration or manipulation of eligibility,” while the Interior Department is instructed to eliminate any policies giving “preferential treatment” to renewable sources. The Administration argues that “the Federal Government has forced American taxpayers to subsidize expensive and unreliable energy sources like wind and solar. The proliferation of these projects displaces affordable, dispatchable domestic energy sources, compromises our electric grid, and denigrates the beauty of our Nation’s natural landscape. Moreover, reliance on so-called “green” subsidies threatens national security by making the United States dependent on supply chains controlled by foreign adversaries.” Similarly, the Department of the Interior tightened reviews of wind and solar projects, noting that “[a]ll Department-related decisions and actions concerning wind and solar energy facilities will undergo elevated review by the Office of the Secretary, including leases, rights-of-way, construction and operation plans, grants, consultations and biological opinions. This enhanced oversight will ensure all evaluations are thorough and deliberative.” The Interior Department has also issued stop-work orders on two offshore wind projects not covered by earlier restrictions on offshore wind development, though one was allowed to resume construction. At the same time, the Administration has loosened regulations on coal, even though generation of electricity from coal has been declining (now at 15%) and now costs more than most electricity generation than from new renewables capacity. Congress and the President also enacted a resolution under the Congressional Review Act reversing the IRA’s waste emissions charge, which will remove incentives to reduce methane leaks in fossil fuel production. (Methane is a potent greenhouse gas but dissipates far more quickly than other greenhouse gases; reductions in methane emissions thus accelerate overall emissions reductions.) The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also began formal reconsideration of its 2009 “endangerment finding” that provides the basis for EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gases (and thus of stationary sources of greenhouse gas emissions, several sectors of which, including sterile medical equipment, coal-fired power plants, chemical manufacturing, and iron ore processing, have now received regulatory relief under the Clean Air Act and EPA’s 2024 National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Pollutants). In essence, all of this puts the Government’s hand on the scale as much as tax credits for renewable energy sources do. By definition, wind and solar are domestic resources as much as fossil fuels. Most types of energy projects have environmental costs, including to the landscape. One purpose of the IRA subsidies was to ensure the US retains global leadership in clean energy technologies, which includes supply chains. With respect to fossil fuels, US oil and gas production has been rising, both in absolute terms and in terms of the order of magnitude of the increase relative to other forms of energy. US production of both oil and natural gas is expected to continue rising this year before falling in 2026 (in the case of oil, from approximately 13.5 million barrels per day to about 13.3 million barrels per day, according to the Energy Information Administration). The US rig count fell to 442 in June, a decline of over 50 in one year. While deregulatory actions can encourage greater production (and strongly regulatory actions can discourage production), markets and prices are—and should be—the principal drivers of production. Implicit in a belief in markets is a further belief that regulation should be as technologically neutral as possible or, in this case, as source-neutral as possible to encourage markets to work well. Putting a hand on the scale in favor of fossil fuels can distort markets just as surely as putting a hand on the scale for other types of energy. For an economy facing accelerating and massive demand for electricity, restricting one type of power source that is growing as a share of electricity production is likely to weaken attempts to meet electricity demand. Fossil fuels will remain an essential and indispensable part of the US energy mix, but markets should determine that mix more than government action. For a nation otherwise so committed to markets, the US remains a global outlier in developing markets for carbon. Economic competitors (including Europe, whose market is worth over $800 billion, Canada, Switzerland, China, Japan, and India) began the process earlier and are reaping the benefits, including real reductions in carbon use in industrial and other processes, reducing costs for companies. From one perspective, the absence of a national carbon market in the US is even more surprising given that the alternative to using markets in this way is subsidies, an approach Congress largely rejected in the OBBBA. In the US, most carbon markets remain voluntary. Markets offer strong incentives for businesses to invest in carbon reductions and avoid picking winners and losers, a principal risk of subsidies. While there are critical technical challenges in designing a system, in the US, the principal challenge is the political difficulty of achieving a carbon market on a national scale. As CED wrote in An Energy Transition Road Map to Net Zero 2050, while there are many ways to design carbon markets (as our international competitors show), an ideal system for the US would combine pricing mechanisms with principles to encourage fairness, including sensitivity to those most impacted by higher costs from higher prices on carbon, such as the poorest and most disadvantaged Americans. The basic principles of such a system are revenue neutrality (including a refund for consumers) so that the system becomes self-funding, promoting net zero carbon, regional coordination to account for differences between states that rely heavily on energy production and those that do not, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism to maintain US competitiveness and ensure that other countries do not simply take advantage of the US’ effort to reduce emissions to boost their own economies. A national system could also have the benefit of ending regulations that use command-and-control policies to push emissions reductions, because the same effect would be achieved through market mechanisms. Policymakers should develop such a plan in coordination with the private sector. In the meantime, voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) for purchase and sale of carbon offsets offer an important way for business to participate in emissions reductions. As these markets grow, it will be essential to ensure that carbon credits are of high quality and deliver the promised emissions reductions. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market has produced The Core Carbon Principles, including disclosure and measuring climate impact, to guide businesses in this effort. The issue is particularly important with credits that are purchased internationally, where it may be more difficult to measure actual impact. But international carbon markets of high quality are growing—a positive development. On a positive note, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s recent approval of the Green Impact Exchange (GIX) as a national securities exchange highlights the role of markets for companies making binding sustainability commitments. Even as the SEC effectively suspended its climate disclosure rule that would have applied to all publicly listed companies, it supported this voluntary effort by companies towards sustainability and demand for systems that demonstrate credible sustainability commitments to investors. Companies choosing to list on GIX must adopt a sustainability reporting framework, including progress reports. Beyond its tax credits, the IRA also included a focus on encouraging domestic production of clean energy and clean energy products, jumpstarting efforts at developing new clean energy technologies and encouraging US exports—including, in essence, through the tax credits as a form of subsidy. For instance, increased solar installation at homes reduces overall pressure on the grid, but the end of the tax credit will likely slow adoption. In many aspects of clean energy research and deployment, US businesses are global leaders, but there is a risk from the end of many of the tax credits and grants in the IRA: losing the US’ advantage in the clean energy market, worth $2 trillion globally, which provides US jobs and increased exports. China is already the world’s largest exporter of green technology, and the US is at risk of falling further behind. Chinese companies, for instance, have made significant advances in electric vehicle charging time, in one case claiming technology that can charge an EV in only five minutes, making EV charging compatible in time with a trip to the gas station. China is already the world’s leading producer of electric vehicles, with over 60% of global production and 80% of EV battery production. Of course, the US competes strongly in EVs and associated technology such as EV batteries, but the scale of China’s production will make it harder for the US to compete globally. Policymakers should carefully consider how to foster US competitiveness and growth in clean energy exports in the post-IRA environment. States will likely have an important role in this, as demonstrated by Georgia’s efforts to promote an EV ecosystem. Similar considerations about the future of US leadership apply with respect to the electric grid. Without adequate connection to the electric grid, other countries, such as India, could become hubs for data centers that might otherwise be situated in the US. India is using renewables to power this growth in data centers; there is no reason the US cannot do so as well, reducing the burden on consumers and overall US electricity demand. Already, the carbon intensity of electricity US data centers is 48% higher than the US average. Using low carbon electricity to power data centers will also reduce domestic demand for fossil fuels, allowing them to be exported (and potentially at higher profits) as opposed to them being used for domestic electricity generation. One urgent goal is to address the current backlog of project approvals. In 2024, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory reported a backlog of nearly 2.6 terawatts of generation and storage capacity. Greater investments in transmission are essential to meet rising demand for power. Too often, regulatory paralysis has prevented quickly adding new projects to the grid, and the problem can be compounded for power grid investments themselves crossing state lines. CED has long believed that permitting reform is key to building and upgrading the power system for the energy transition and greater reliability. States should not have the power to block interregional transmission lines; more ambitious reforms include limiting judicial review of permitting decisions and imposing barriers to standing in court. The Administration has taken strong action on permitting reform. Perhaps surprisingly, permitting reform is an area in which to find common ground in energy policy, with some environmental groups championing it as essential to advancing renewable energy projects and their connection to the grid. Ohio’s recently enacted permitting reform legislation, HB 15, addresses key issues, including jurisdiction over the process, timelines, fees, and grid reliability, as well as eliminating subsidies. It passed with strong bipartisan support. Even after—perhaps especially after—the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change, US business still has an active and urgent role to play in leading energy innovation and growing exports of clean energy products as well as promoting emissions reductions at home. It is time for reengagement, in which US businesses should take the lead, in this increasingly important global industry. Maintaining a strong role for US business will be essential both for global leadership and for progress in the energy transition. In so doing, it will be important to find common ground among those seeking to continue a trajectory to a sustainable energy future and those focused on greater US energy production. An “all of the above” strategy, relying to the extent possible on markets, will be the best way to ensure alignment and thus real progress, avoiding regulatory distortions and letting businesses adopt solutions that best meet their needs. As with permitting reform, imagining this common ground is less difficult than may appear. Consider, for instance, initiatives for low carbon biofuels, innovations for wind and solar that make them cost competitive (such as storage and grid balancing technologies, raising the efficiency of electricity transmission, innovation to reduce the carbon footprint of traditional technologies, and efforts to bring carbon capture and storage (CCS) to scale, including innovations such as direct air capture and removing carbon dioxide from the ocean. Business is already becoming more deeply involved in efforts at carbon capture and storage. Ideally, CCS works best when carbon is not released into the air at all; instead, it is best to separate it from other gases, then compress and (if necessary) transport it. Climate-related disasters are exceptionally costly to the US, and the costs—both economic and human—are expected to rise. Business has a strong interest in avoiding those costs to operations. Equally, businesses of all sizes can take significant steps to reduce energy consumption, thus reducing carbon emissions, and improve energy efficiency in business operations, in their supply chains, and in other emissions reduction efforts such as decarbonizing buildings, increasing energy efficiency in homes, and promoting resilience to respond to climate change (for instance, construction that is better able to withstand more powerful hurricanes). Despite changes in public policy, many businesses continue to regard achieving net zero as a business imperative, particularly with new technologies that can offer cheaper and more reliable energy while also being more sustainable. Increasing use of solar power in commercial buildings is just one example of this. Finally, businesses are best positioned to connect new, low carbon technologies to customers by designing products with their customers in mind, ensuring that customers will be receptive (and even eager) to purchase new low carbon options. One risk of the US withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement is that US business could be sidelined as other nations continue to work on emissions reductions. To lessen this danger, US businesses and business groups should remain engaged in global business and global energy forums, including the meetings of the Conference of Parties to the Paris Agreement. Business leaders should stay engaged, not least to help increase US clean energy and LNG exports. They should also promote the use of new technologies and innovation to mitigate the effects of climate change, including through encouraging limited trade agreements for these technologies, on the model of the 2020 agreement with Japan and the more recent 2023 US-Japan Critical Minerals Agreement. These types of agreements can lead to both increased US exports and more secure US supply chains. US energy strategy—“all of the above”—can and should include both sustainability and expanding production of fossil fuels. Only in this way can the policy of energy independence be truly sustainable—in both senses of the word—and provide the country with safe, affordable, and reliable energy and businesses of all types with the flexibility they need to meet their growing energy needs. It is time to find unity and common ground on energy policy, an area which has seen too much division in the past. Finding that common ground is an urgent task for policymakers at all levels of government, to ensure that the energy independence the US has recently gained is secure and stable and that the energy mix reflects the rich diversity of US energy resources and takes full advantage of the talents of energy scientists and engineers.Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Policy Recommendations

Sustaining Energy Independence

What does “energy independence” really mean?

Sustaining Energy Independence

The Power of Markets

The IRA and OBBBA

Regulatory Neutrality

Carbon Markets

Promoting US Clean Energy Exports

The Electric Grid and Permitting Reform

The Role of Business and the Global Dimension

“All of the Above”

The US has achieved the long-desired goal of energy independence. Now, the goal is to sustain these trends.

learn more250 Years Forward

January 20, 2026

250 Years Forward: Strengthening an American Future

January 20, 2026

Navigating the Health Care Landscape in 2026

December 01, 2025

US Lead in Public R&D Is Eroding

October 20, 2025

Maintaining the US Lead in Science and Technology

October 20, 2025