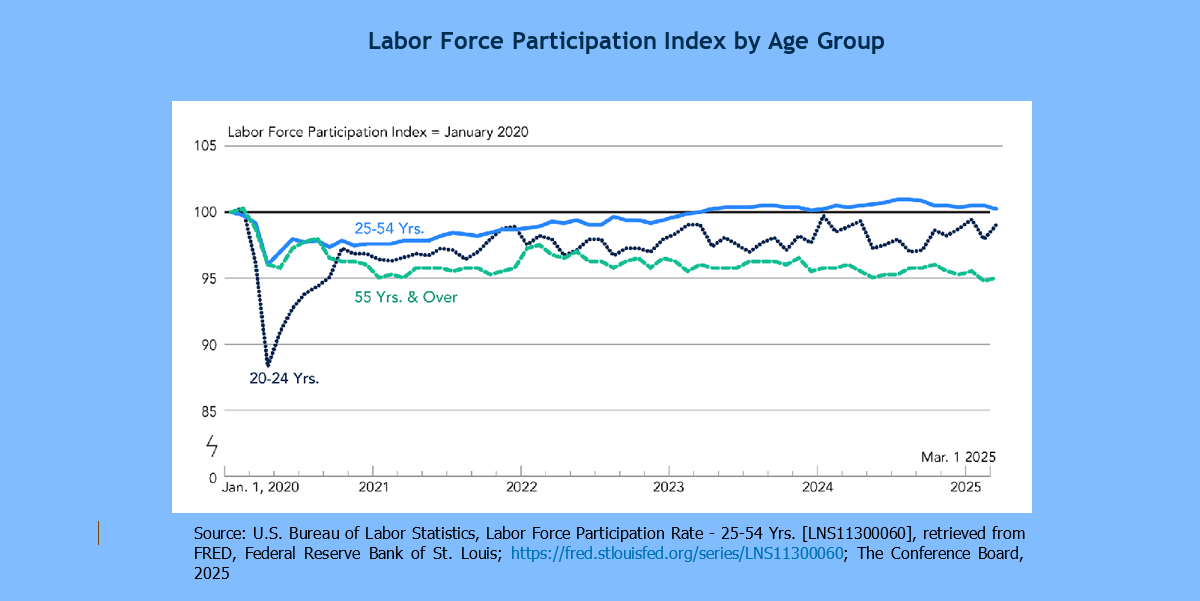

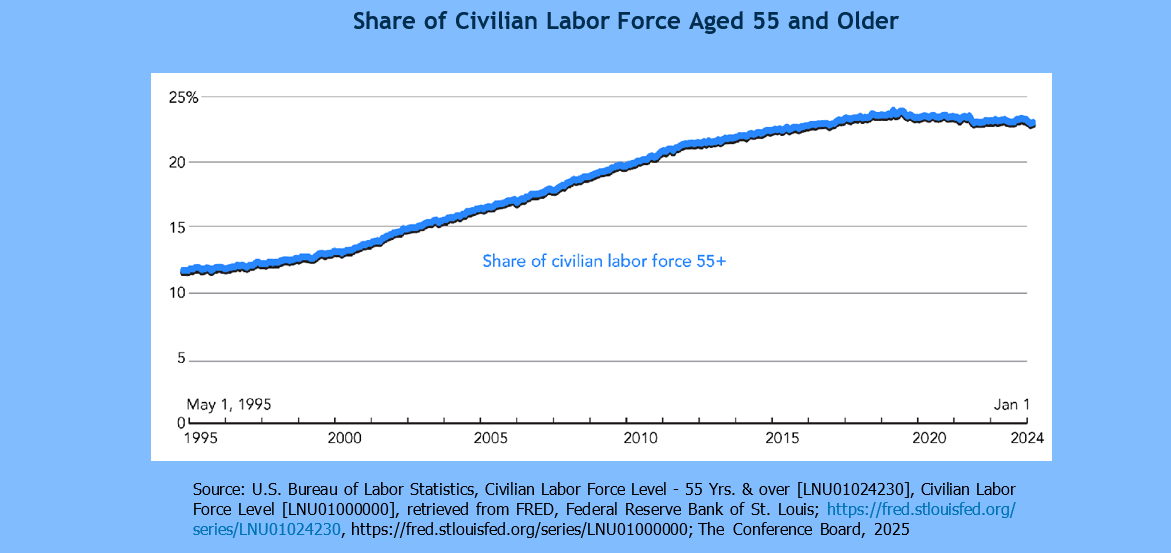

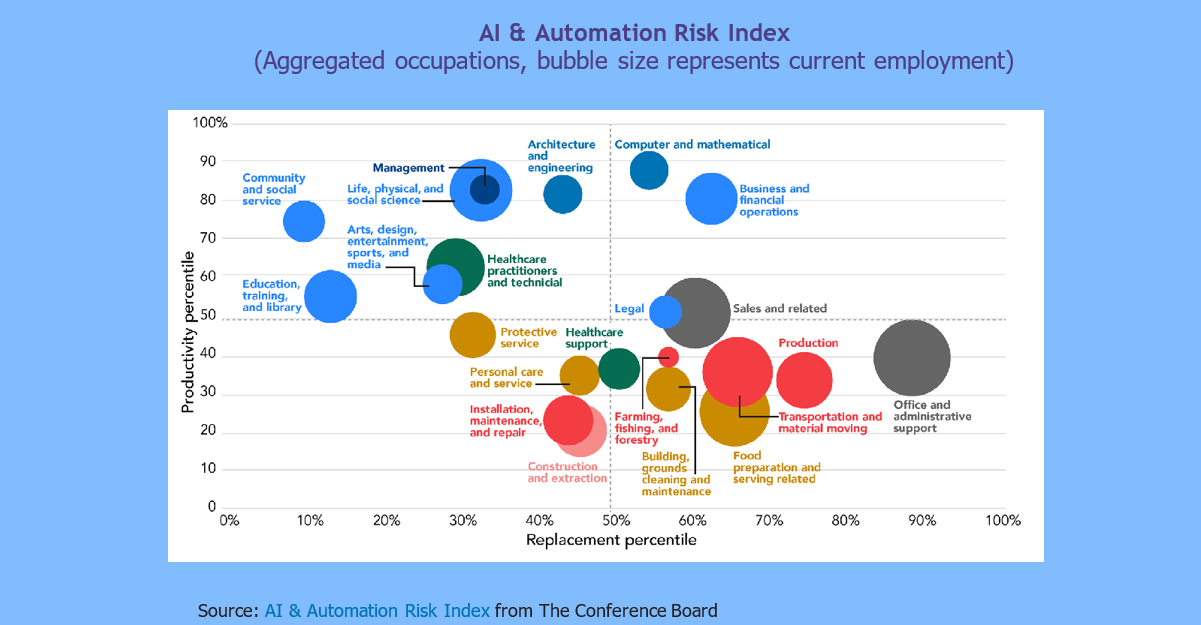

Demographics have historically been a tailwind for the US economy. However, with an aging labor force and projected population shrinkage, existing labor shortages may grow, hindering economic growth and making businesses less competitive. Artificial intelligence (AI) may help alleviate some shortages, but the technology’s net effects are uncertain. Prudent policy measures and public-private collaboration are urgently needed to respond to these challenges and ensure the workforce is prepared to meet rapidly evolving needs. Labor shortages pose a growing risk to US economic growth and competitiveness. To respond effectively, policymakers should adopt targeted reforms that remove barriers to labor force participation, increase the supply of workers, and invest in skills development. Policymakers should seek to remove these barriers driving differences in labor force participation across key factors, including age and parental status: Policymakers should modernize immigration policies to ensure sufficient influxes of workers with in-demand skills while simultaneously strengthening measures to reduce unauthorized immigration, including: Policymakers should prioritize removing outdated or overly burdensome regulations that limit opportunities to enter the workforce or start a business. This should include regular comprehensive reviews of licensing requirements to ensure they are necessary, proportionate, and not unduly restrictive. In addition, policymakers should con- sider streamlining processes for obtaining licenses, recognizing out-of-state credentials, and reducing or eliminating licensing requirements for low-risk professions. Preparing the workforce for a rapidly evolving economy requires modernizing education and training systems to better align with industry needs, expanding access to alternative pathways, and supporting ongoing upskilling for all workers, including: The US labor force has long been fueled by steady population growth, but that momentum has slowed considerably in recent decades. After averaging annual increases of about 2% annually from 1960 to 1989, labor force growth has slowed to about 0.66% annually from 2004 to 2024, roughly mirroring trends in population growth. However, The Conference Board estimates that the US needs to add 4.6 million workers (about 4 times the average rate over the last 10 years) annually to keep pace with current levels of supply, demand, and population balance. This demands an urgent and comprehensive policy response. Underneath aggregate changes to the labor force, its compositional dynamics have been far more fluid, shaped by evolving demographic, economic, and social trends. For example, the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for prime-age (25 to 54) men has been declining for decades due to a variety of factors, including extended periods of schooling, increased caretaking or family obligations, disabilities, and skills mismatches. In particular, less educated young men appear to be struggling, with LFPR for high school educated young men falling from about 98% in 1970 to 87% in 2023. Recent scholarship has raised broader concerns about the overall well-being of young men across a variety of factors, including economic opportunity, mental health, and educational attainment. These are important issues that deserve atten- tion from policymakers and business leaders. Meanwhile, women’s participation has steadily increased, reflecting broader shifts in educational attainment, household labor arrangements, gender norms, and economic necessity—though it still lags LFPR for men. Importantly, gender-based disparities in LFPR persist when analyzed by marital status and the presence of young children. Married women and mothers of young children remain less likely to participate in the labor force than single women or women without children, a pattern rooted in long- standing caregiving responsibilities, societal expectations, and institutional barriers. Tax code structures and other policies that disadvantage secondary earners—primarily women—further suppress participation. In contrast, men with children are more likely to be in the labor force than their childless counterparts. These patterns are gradually evolving. With rising female educational attainment and earnings—women now outpace men in postsecondary degree completion and increasingly contribute as primary or co-primary earners—labor market gaps are narrowing. However, a critical constraint to full labor market participation remains the high cost and limited availability of childcare, which disproportionately affects women as primary caregivers. Uneven access to paid parental leave and the challenges of eldercare present additional barriers for workers who are also caregivers. Racial disparities in labor force participation have also persisted over time. Black men aged 25 to 54 have consistently participated in the labor force at lower rates than men over- all, while Black women have often exceeded the participation rates of women more broadly. These differences stem from complex factors, including educational access, employment discrimination, and disproportionate incarceration rates. Understanding these dynamics can help policymakers identify potential solutions. CED last released a Solutions Brief on labor shortages in 2022, just as the US was emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic—by many measures the most disruptive economic event in a century—which had profound effects on the labor market. At the peak of the labor shortage in March 2022, nearly 8% of private sector jobs were unfilled—more than double the average vacancy rate over the prior two decades. At that time, about 12 million jobs were unfilled, with only 6 million people unemployed. The labor market has recovered significantly since then, with about 7 million nonfarm jobs unfilled as of March 2025, and the ratio of open positions to unemployed work- ers is roughly in balance. However, the pandemic has left enduring imprints on labor dynamics, and structural challenges—most notably an aging population—continue to constrain long-term labor force growth. Certain occupations, particularly home health and personal care aides, are expected to see significant demand in the next decade as both workers and the populations they serve age. These trends are projected to exacerbate healthcare worker shortag- es, including a shortfall of about 187,000 physicians, 208,000 registered nurses, and 302,000 licensed practical nurses within the next decade. An estimated 2.1 million manufacturing jobs may also go unfilled by 2030, and homebuilders report severe shortages of carpenters, masons, plumbers, electricians, and other trades. The rise of artificial intelligence presents an additional layer of uncertainty, potentially easing labor shortages in some sectors and creating additional labor demand in others. The pandemic’s effects on the economy and labor market were dramatic and far- reaching, as 8.2 million people exited the labor force between March and April 2020. Economic activity—boosted by easing public health restrictions and fiscal stimulus— quickly recovered, but labor supply remained constricted. It took about two years for labor supply to rebound to prepandemic levels, a key factor driving persistent inflation. CED staff analysis indicates that had prepandemic labor force growth trends continued, the labor force would include approximately 3 million additional workers today. The labor market has now largely rebalanced, with the gap between the ratio of open jobs to unemployed workers nearly closed. However, one of the most persistent labor market effects of the pandemic has been the continued decline in labor force participation among older workers. While labor force participation for prime-age individuals reached near-record highs at nearly 84% in April 2025 and participation among younger workers (ages 20 to 24) has nearly returned to prepandemic levels, LFPR among older workers has not recovered. Labor force participation for individuals over age 55 remains approximately 5 percentage points below its prepandemic level. If participation among this group had returned to prior trends, the labor force would include roughly 2 million additional workers today. It is unclear to which degree this persistent gap is due to population aging—that is, the population over 55 skewing older on average than in 2019, and thus less likely to have worked anyway—or excess retirements—that is, individuals over 55 who would have continued working, but chose to retire from a pandemic effect (e.g., health concerns or wealth effects). As CED noted in its 2022 Solutions Brief, an aging baby boomer population combined with historically low birth and fertility rates are providing a significant drag on labor force growth. Americans aged 65 or older accounted for just 12% of the population in 2008, but are projected to account for 21% of the population by 2030. Furthermore, the share of the civilian labor force aged 55 or older has nearly doubled between 1995 and today. Even before the pandemic, economists expected the LFPR to decline along with an aging population by about 1 percentage point by 2031. However, the sudden and persistent drop in LFPR among those aged 65 and older during the pandemic may double the drop in LFPR by 2031. Workforce aging also has uneven effects across occupations. For example, between 2014 and 2024, the percentage of personal care aides over 55 increased from 28% to 34%. Police officers over 55 increased from 10% to 15%, and construction workers from 14% to 17%. Population aging trends vary across the US, leading to differing impacts on states’ LFPR. Among the 10 states with the lowest projected concentration of those aged 65 or older, the LFPR was more than 3 percentage points higher than in the 10 states with the highest projected concentration of those aged 65 or older. Falling fertility rates over the last 50 years have also impacted the current and future labor force. While US women in the mid-1960s averaged about 3.5 children in their lifetimes, that figure fell precipitously in the next decade, reaching a then-record low of about 1.7 children in the mid-1970s. Fertility rates remained stagnant over the next 40 years, but began falling steadily again in 2007, reaching a record low of 1.6 children in 2023. Importantly, declining birth rates have also been associated with sharp increases in LFPR among women, offsetting some of the effects of declining birth rates. However, given the direct link between population age and labor force participation, these trends have profound implications for the US labor supply. Amidst these trends, immigration plays an increasingly important role in sustaining population growth and adequate labor force supply. US population growth is now one-third its rate in the 1960s—had US population growth continued at its 1960s rate, an additional 70 million people would live in the US. Importantly, between 2020 and 2024, immigration accounted for 83% of net population growth. In fact, 20 states would have lost population without immigration. Immigrants play a particularly vital role in certain sectors of the US economy. In construction, for example, foreign-born workers represent about 29% of the workforce. In other key sectors, including professional and business services, transportation and utilities, leisure and hospitality, manufacturing, and agriculture, immigrants fill at least one in five positions. Immigrants also play a critical role in filling shortage in STEM occupations—nearly half of international students in the US are enrolled in STEM programs and foreign students account for about one-third of all STEM doctoral degrees. In certain fields (e.g., economics, computer science, engineering, and math), foreign students account for more than half of all awarded doctoral degrees. Research indicates that immigration played a key role in addressing labor shortages following the pandemic, and industries and states with large immigrant inflows saw sharper reductions in job vacancy rates between December 2021 and 2023. By also tempering wage growth, immigration helped ease inflationary pressures from wages on low-skill positions. In the longer term, research indicates that immigration has a positive effect on wages for native workers and no significant effect on wages for college educated native workers. Importantly, LFPR tends to be higher for immigrants than for the native born, reflecting, in part, that a higher percentage of immigrants are in their prime working years compared to nonimmigrants. Analysis from the Economics, Strategy & Finance Center of The Conference Board indicates that mass deportations of unauthorized workers of 1 million individuals per year for four years would contribute to labor shortages, and by 2027 result in a net labor force shrinkage. Sectors particularly dependent upon non-citizen labor (which includes both legal and unauthorized immigrants), including agriculture, building and grounds maintenance, construction, and food preparation and serving are particularly vulnerable to labor shortages resulting from mass deportations. While artificial intelligence is poised to significantly affect the labor market, the full scope and nature of its impacts remain uncertain. By some estimates, nearly 2% of jobs could already have over half their tasks affected by AI today, a figure that may increase to 46% of jobs when accounting for likely future innovations. However, survey data from fall 2024 indicate that AI adoption in the workplace is still relatively modest. Evidence from the adoption of the personal computer in the workplace suggests that for those equipped with the skills needed to excel in AI-augmented positions, the economic returns may be significant. Despite the gradual adoption, computer use was linked to substantial productivity growth, averaging 1% annually between 1991 and 2004, nearly double the rate observed during the 1980s. At the same time, the wage premium for workers with at least a college degree compared to those with only a high school degree roughly doubled between the early 1980s and early 2000s. The median college graduate now earns about $80,000 per year compared to $47,000 per year for a high school graduate, a premium that tends to widen over the course of a worker’s lifecycle. Though it remains to be seen how AI will impact worker productivity and wages, recent studies measuring task speed and quality have estimated potential AI productivity gains may range from 8-36% thus far. Research to date suggests that AI may have heterogeneous effects on labor demand—potentially reducing demand for lower-skilled cognitive tasks that can be readily automated—while simultaneously increasing both the demand for and the skill requirements of roles that involve collaboration between humans and AI systems. These contrasting effects may offset, resulting in minimal effects on overall labor demand. Additional research from The Conference Board has found that certain occupations (e.g., management, science, and healthcare) may experience significant productivity gains and low risk of job loss. Conversely, other occupations, such as building and grounds maintenance, transportation, and food preparation are at risk of significant job loss. In addition, shifts in labor demand that displace workers may result in increased need for various government support programs. Ongoing high- quality research is essential to understanding and projecting the long-term effects of these trends. This underscores the importance of upskilling the existing labor force, preparing cur- rent students for an AI-enabled workplace, and adopting immigration policies that allow US firms to recruit and retain AI talent from around the world. It is critical to understand these labor demand dynamics as the economy undergoes transformation alongside the adoption of AI. Having a sufficient number of workers is necessary but not fully satisfactory; workers must also possess the skills required to perform emerging tasks effectively. In the context of AI, this means that addressing labor shortages requires not just expanding the workforce but also aligning worker skillsets with the demands of rapidly evolving technologies and work demands. In an earlier report, The Conference Board highlighted the “existing or potential shortage of skilled labor,” noting a skills mismatch between the needs of employers and those seeking work. The report noted that technological innovation was leaving many workers unprepared for the demands of the future workforce and that government policy risked exacerbating the shortage. Though it was 1935, and the US was in the midst of the Great Depression, employers observed that the existing workforce was unprepared for new manufacturing techniques and that apprenticeship programs and partnerships between the government and private sector would be needed to address the shortage. Citing this report in 1939, a labor economist noted the paradoxical conditions of the early 1930’s labor market—high unemployment coupled with shortages in certain sectors accompanied by an aging population, declining birth rates, and a skills mismatch. This research is informative as the US again faces uncertainty stemming from demographic shifts and technological innovations with significant implications for the labor force and economy. A comprehensive policy agenda is needed to respond to these factors—both immediate (e.g., pandemic shocks) and structural (e.g., an aging population) —that continue to affect the labor market. This agenda should advance four priorities: maximizing labor force participation, strategically increasing immigration, reducing barriers to work and entrepreneurship, and addressing educational and skills mismatches. As noted earlier, aggregate labor force participation has recovered significantly since the onset of the pandemic. However, addressing persistent LFPR disparities across key demographics, including gender, parental status, race, and age, can further improve LFPR and improve labor supply. Key strategies include minimizing disincentives to work for older individuals, enhancing support for low-income workers, and expanding access to flexible work arrangements and childcare services to increase labor force participation among parents and women. Social Security retirement benefit recipients who opt for early retirement (after age 62, but before age 67 for those born after 1960) are subject to a retirement earnings test (RET), which limits how much a recipient can earn without having some benefits withheld—in 2025, $23,400 or $62,160, depending on the recipient’s age. The with- held benefits are not permanently forfeited; instead, they are added to the recipient’s benefit once they reach full retirement age (FRA). The RET has been part of Social Security since benefits were first paid in 1940, reflecting Congress’s intent view that “there is no need for payment of old-age benefits to employees who continue in employment.” However, in part responding to criticism that the RET discourages work, Congress made changes over time, including by lowering the age limit at which the RET is eliminated and adjusting the earnings thresh- olds. The most recent changes were made in 2000, when Congress eliminated the RET beginning in the month the beneficiary reaches FRA to incentivize older workers to participate in the labor force. Though research is mixed on the effect of the RET on labor decisions among older adults, studies generally indicate that RET repeal would increase work among certain groups (e.g., those with lower incomes near the RET thresholds). The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), introduced in 1975 as an antipoverty and work incentive measure, subsidizes earnings for low- and moderate-income individuals, particularly those with children. Designed as a refundable tax credit, the credit amount increases with earned income up to a maximum threshold, then phases out at higher income levels. Benefits are substantially more generous for workers with children, while childless workers receive much smaller credits. In 2024, for instance, a single filer with three children could receive a maximum credit over $7,830, whereas a filer without children could receive a maximum of $632. Research generally finds the EITC has positive effects on employment and poverty reduction, with studies finding the strongest positive effects on LFPR among single mothers—ranging from about 2.9 percentage points to 7.5 percentage points in some widely cited studies. Notably, evidence on positive effects on hours worked is less clear and some studies dispute findings of the EITC’s positive effects on employment. Policymakers should consider targeted expansions of the EITC to maximize its positive effects on LFPR. These may include enhancing benefits for workers without children, eliminating the arbitrary age restrictions that make those under 25 or over 65 ineligible, and increasing phase-in rates to make work pay off more quickly at lower income levels. Flexible work arrangements that flourished during the pandemic—including tele- work, hybrid schedules, and adjustable working hours—have been found to support LFPR, particularly among certain groups. For example, women with young children at home experienced the largest increases in LFPR during the pandemic, and research indicates that the availability of remote work has supported greater LFPR for prime- age women generally. A Federal Reserve study argues that an expansion of the set of jobs that can be performed remotely between 2003 and 2023 has led to about a 4-percentage point increase in LFPR for prime-age women. Research has also found that significant shares of both men and women would be willing to take a pay cut in exchange for remote work. Given the significant role that having children plays in the gender pay gap, flexible work may play a role in boosting pay for women. Remote work has also supported more active caregiving time for both mothers and fathers. Shifting work arrangements during the pandemic also has supported greater labor force participation for people with disabilities, whose LFPR increased nearly 4 per- centage points between 2019 and 2022, while LFPR for those without disabilities remained flat. The gap in hours worked and average hourly wages between those with and without disabilities also shrank during the pandemic, particularly among those with disabilities who worked remotely. Flexible work arrangements also sup- port employment for caregivers, which has important labor market implications in an aging population. For example, studies indicate that older workers providing informal care are more likely to flexible work arrangements, particularly time off and flexible work schedules. Of course, many jobs cannot be performed remotely, and flexible schedule arrangements may create operational challenges for some employers. However, policymakers should consider approaches that make remote work possible, such as investing in broadband access in rural communities to support remote work, and employers should consider supporting flexible work arrangements. Men with children continue to be significantly more likely to participate in the labor force than women with children, reflecting, in part, differing childcare responsibilities, particularly among parents of young children. For example, in 2023, women in households with children under the age of 18 spent about 54% more time each week on childcare than men. However, the high cost of paid childcare is a major expense for many households, with prices ranging from 8% to 19.3% of median family income per child depending on the state. Studies indicate that the high cost of childcare is one barrier to greater LFPR for primary caregivers, who are typically women. Expanding access to affordable childcare would likely have positive LFPR and employment effects for parents, particularly low-income women. For example, an analysis of the impact of the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), which provides childcare assistance for low-income families, found positive effects on both LFPR and employment. Other programs that assist with childcare, such as Head Start, also have positive effects on employment for parents (in addition to benefits for children). Sup- porting the childcare sector also has significant benefits for the economy—research from CED found that the organized childcare sector generated a total economic impact of $152 billion in 2022 and supported 2.2 million jobs. To assist with access to and the cost of childcare, policymakers may consider several options. For example, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) allows eligible tax filers to claim a nonrefundable tax credit for childcare expenses up to $3,000 for one child and $6,000 for two or more. Filers can claim between 20-35% of the allowed expense amount, depending on income. As a result, most families are eligible for a maximum credit of between $600 and $1,200. In 2020, about 5 million tax returns claimed the credit for an average amount of $560—far short of the cost of childcare, which in 2022 typically ranged between $6,500 and $15,600. Policymakers could consider adjustments to the CDCTC, such as increasing the cap on allow- able expenses or increasing the credit rate, to provide additional financial assistance. Policymakers may also consider expanding the types of eligible childcare covered by the CDCTC. Current definitions exclude many nontraditional and informal care arrangements that families, particularly those working nonstandard hours, rely upon. Recognizing a broader array of licensed home-based providers, relatives providing care under formal agreements, and cooperative care models would increase flexibility and access. Beyond tax policy, addressing childcare supply constraints is equally critical. Increasing the size and sustainability of the childcare workforce—a sector plagued by low wages, high turnover, and insufficient pipeline development—is a necessary pre- condition for expanding access. Policymakers may consider increasing funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant—a Department of Health and Human Services analysis found that increased CCDBG funding provided during the pandemic led to 300,000 new childcare slots. Leveraging Small Business Development Centers to providing technical assistance and other support to providers would provide additional benefits. Employers also have a role to play; research indicates that providing childcare benefits, for example, improves employee retention and reduces absences. A significant number of companies operate on-site childcare facilities, subsidize or provide financial assistance for off-site childcare, or support backup childcare and elder care options. Expanding the Dependent Care Assistance Program and the Employer-Provided Child Care Tax Credit, and resolving interactions with the CDCTC that make these policies less effective, would further assist working parents and enhance employer- supported childcare. Because of US demographic trends—including an aging population and declining birth rates—constraining the domestic labor supply, immigration reform represents a crucial lever for sustaining economic growth and labor market dynamism. Policymakers should implement comprehensive immigration reform that improves enforcement of existing immigration laws, expands opportunities for legal immigration, provides a pathway (with stipulations) to legal status for individuals already in the country il- legally, and retains foreign graduates of US colleges in high-demand fields. Effective immigration policy requires public trust in the integrity of the immigration system. Enhancing border security and reducing employment of unauthorized im- migrants are key pillars of this approach. However, significant investments and policy changes are needed to make immigration enforcement and employment verification more effective. Congress has increased appropriations for US Customs and Border Protection and ICE; however, additional resources, particularly for the immigration court system—the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR)—are needed. Between 2019 and 2024, the number of pending cases in immigration courts increased from 1 million to 3.6 million from a variety of factors, including limited court staffing, increases in illegal border crossings and enforcement, and pandemic-related disruptions. This backlog is harmful to both the orderly operation of the US immigration system and the immigrants themselves. For example, aver- age wait times for decisions on asylum claims exceed four and a half years. Congress should provide EOIR with the resources it needs to reduce this backlog. Employers and the government should also work together to make confirming immigrants’ eligibility for employment through E-Verify more effective. First piloted in five states (California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas) in 1997, is primarily a voluntary program that allows employers to submit information provided on an employee’s I-9 form (name, date of birth, Social Security number, and other information) to the Department of Homeland Security, which compares the information with government records and confirms the individual’s employment eligibility. However, employer adoption has been slow—according to DHS, only 1 million employers (of about 6.4 million employer firms) are enrolled in E-Verify—and even in states where E-Verify use is required by law, fewer than 60% of hires are submitted to E-Verify. Furthermore, only about 2% of employees submitted to E-Verify were rejected as not authorized for work, even though unauthorized workers account for about 5% of the US work- force, suggesting that unauthorized workers may simply avoid E-Verify employers. Still, research indicates that when E-Verify and other employment enforcement mechanisms are implemented effectively, employment of unauthorized workers drops. Expanding E-Verify to a national mandate, coupled with investments in system integrity and user support, could deter unlawful employment practices without significantly burdening employers. Enhanced enforcement should be paired with expanded opportunities for legal im- migration. The US offers a variety of temporary employment-based visa programs as well as employment-based preferences for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status (“green cards”). However, statute establishes limits on the availability of these visas that are far short of market demand and severely outdated. For example, employment-based green cards are capped at 140,000 per year, a limit which was established in 1990. The US also offers a variety of nonimmigrant visas, including H-1B for individuals in “specialty occupations,” typically highly educated individuals working in STEM fields. Despite strong demand for H-1B visa workers from US employers, Congress has not increased the limit of 65,000 plus 20,000 for those with advanced degrees since 1990 (though it has exempted some workers from the limit over time). In 2025, for example, employers requested H-1B visas for about 470,000 individuals and only 135,000 were approved (including those that do not count against the statutory cap). Demand similarly exceeds supply in the H-2B visa program for temporary nonagricultural workers, often used in occupations such as landscaping, meat and seafood processing, and construction. To align immigration with labor market needs and maintain US economic competitive- ness, policymakers should significantly expand employment-based visa allocations and expedite visa processing, particularly for high-demand occupations. Streamlining and expanding these programs, particularly for STEM occupations, would allow US employers to access the talent needed to maintain global competitiveness and ease labor shortages in critical sectors. For example, research indicates that barriers to acquiring talent through immigration hinder growth of new technology firms. In addition, research finds that H-1B visa holders do not displace native-born college- educated workers. Spouses of certain visa holders should also be eligible for work authorizations. Policymakers should provide a pathway to legal status for those who initially entered the US illegally—for example, those currently protected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or otherwise meet DACA requirements but are ineligible because of arriving after June 2007—but who meet certain criteria (e.g., sustained employment). Approximately 8.3 million unauthorized immigrants work in the US (about 5.2% of the workforce). These include about 1.5 million in construction, 1 mil- lion in restaurants, and 320,000 on farms. As CED has noted previously, their illegal status bars them from employment in the formal economy, places them at risk of exploitation, and limits their economic potential. Consistent with a 2013 bipartisan proposal, a path to legal status for those currently in the country illegally should include extensive screening with real-time record checks and the collection of biometric information consistent with procedures currently used by CBP. Finally, the US should provide streamlined pathways to work authorizations for foreign graduates of US colleges. Approximately 1.1 million international students enrolled in US colleges for the 2023–2024 academic year, and in 2019, international students earned the majority of advanced degrees in certain science and engineering fields, including economics (62%), computer science (59%), engineering (58%), and math and statistics (51%). Policymakers should ensure that the US remains the premier destination for talented international students to receive postsecondary education. To retain these highly educated students, policymakers should consider extending the length of time allowed under the Optional Practical Training Program for foreign graduates of US colleges and allow certain visa holders to self-petition for permanent residence without a sponsor after completing specified requirements. The pathway to permanent status should be made near-automatic for immigrants desiring it who have successfully met all requirements during their temporary visa term. Retaining foreign graduates in high-demand sectors represents a low-cost, high-yield opportunity to expand the skilled labor force. Moreover, research shows that high- skilled immigrants contribute disproportionately to innovation, entrepreneurship, and productivity growth. Research also indicates that increasing high-skill immigration boosts economic growth, reduces federal debt, and increases wages. Occupational licensing, while initially focused on protecting public health and safety, has, in many cases, expanded far beyond its original intent, creating unnecessary barriers to labor force participation and limiting economic mobility. Today, roughly one in four US workers requires a license to perform their job, a dramatic increase from about 5% in the 1950s. The proliferation of licensing requirements, particularly in lower-risk professions such as hairdressing, cosmetology, and interior design, imposes significant costs on workers, consumers, and the broader economy. Licensing regimes often demand lengthy education and training, costly fees, and inconsistent standards that make it difficult for workers to enter or move between professions. Research indicates that licensing requirements can reduce the number of service providers and make it more difficult for customers to find qualified workers to provide services. Licensing requirements also have disproportionately excluded immigrants, people of color, and low-income individuals from the labor market. Licensing can also function as a form of labor market "protectionism," artificially restricting competition and inflating prices without commensurate improvements in quality. Policymakers should consider implementing regular reviews of the necessity of various licensing requirements, with a focus on sunsetting unnecessary requirements and reducing burdensome fees. In addition, states should coordinate licensing requirements to facilitate the transferability of licenses across state lines. States should also examine the demographic characteristics of license recipients to identify and address disparities in access to licensed occupations. With AI and other technological innovations shaping the future of work, it is essential that workers receive the education and training needed to succeed in an evolving economy. Collaboration between employers and educators can help ensure that students develop the skills and experience most desired by employers. Particular attention should be paid to sectors with severe shortages, including healthcare, construction, and manufacturing. Apprenticeship programs are a particularly important strategy for building in-demand skills and work experience among students. At the federal level, apprenticeships are governed by the National Apprenticeship Act (NAA). Under the NAA, the Department of Labor (DOL) establishes national standards for apprentice- ship programs and provides information to apprenticeship sponsors. However, the NAA has not been modernized since it was passed in 1937, and the number of ap- prentices has not kept pace with the growing workforce. In 1949, there were about 230,000 apprentices in the US representing about 0.37% of the workforce. However, by 2015, the number of apprentices had only increased to about 360,000, representing just 0.22% of the workforce. Apprenticeship participation has increased in recent years as policy changes and shifting attitudes about work-based learning have increased interest. For example, since 2016, Congress has steadily increased appropriations to DOL (from $90 million to $285 million in 2024) to support apprenticeship expansion. Over this period, the number of active apprentice- ships has increased from about 400,000 to nearly 680,000. The additional funds have supported grants to state apprenticeship agencies and partnerships with stakeholders providing apprenticeships in key sectors, including cybersecurity, K-12 education, health care, and supply chains. Still, there is room for improvement. About two-thirds of apprenticeships occur in construction trades, but apprenticeships are available across a wide range of industries. Increasing employer and worker awareness of apprenticeship programs and simplifying their enrollment will increase participation. In addition to apprenticeships, policymakers, educators, and employers should facilitate additional work-based learning partnerships, curriculum co-design, and advisory boards to ensure alignment students’ education with business needs and introduce students to potential career options. Several models of collaboration between schools and employers may offer potential. For example, in Colorado CareerWise offers a youth apprenticeship model (based on the Swiss apprenticeship system), placing high school students into three-year paid apprenticeships where they earn credentials while completing their schooling. The P- Tech 9-14 School Model, developed and supported by IBM, enables students to earn both a high school diploma and a two-year postsecondary degree in a STEM field at no cost. Some jurisdictions also actively partner with employers to shape school curricula. The California Strong Workforce Program, which provides career and technical education (CTE) through the state’s community colleges, mandates engagement with local stakeholders, including employers and local workforce development boards. The Academies of Nashville program involves industry partners in shaping high school curricula around themes like healthcare, IT, and engineering. The US is facing a particularly acute shortage of workers in skilled trades, including electricians, plumbers, and welders. By some estimates, demand for skilled trades roles will grow 20 times faster than overall job growth in the next decade. Coordinat- ed efforts across government as well as educators and employers are needed to fill this void. The federal government supports CTE and workforce development through a variety of complementary and, at times, overlapping programs. Two cornerstone pieces of legislation—the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) and the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act (Perkins V)—form the backbone of this system. State and regional programs also play an important role in CTE and workforce development. Federal CTE funding for secondary and postsecondary students is provided primarily through the Perkins Act (or Perkins V). Perkins supports CTE students in public schools and technical and community colleges primarily by providing grants to states, which distribute funds to providers. Though Perkins funding has increased since 2017, it has not kept pace with inflation. Had appropriations been increased to keep pace with inflation since 2010, an additional $200 million would have been provided in 2024 (out of an appropriation of about $1.5 billion). In addition, regulations implementing Perkins funding penalize states that reduce state funding for CTE. Though intended to prevent states from backfilling their own cuts with Federal funds and thus increasing overall CTE funding, this approach can be counterproductive, penalizing states experiencing lost revenue with struggling economies which would benefit from investments in CTE. Enacted in 2014 (replacing the earlier Workforce Investment Act of 1998), the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) targets adults and dislocated workers, job seekers, incumbent workers, and in- and out-of-school youth by funding career services and job training programs. It authorizes core programs including job training, adult education and training, career centers, and vocational rehabilitation services to individuals with disabilities. WIOA’s funding structure is primarily formula-based, distributing appropriations to states using factors such as unemployment rates and concentrations of disadvantaged populations. However, appropriations have not kept pace with inflation over the past decade, limiting system responsiveness amid rapidly evolving labor market dynamics. In addition to increasing funding for existing programs to keep pace with inflation and need, policymakers should improve coordination across the various federal education and labor programs. For example, differing performance metrics and data definitions introduce administrative challenges and complicate program evaluation. The Federal government should also facilitate increased state adoption of combined strategic plans for Perkins V and WIOA, which are required by each law. Though Federal law has allowed states to submit combined plans since 2015, only nine states have opted to do so as of 2024. Policymakers should also prioritize expanding research into the effects and benefits of various CTE programs. Existing research establishing causal relationships between participation and positive outcomes, such as increased earnings, remains limited and is often based on small-scale studies focused on a narrow set of institutions. Many studies have raised important considerations for policymakers that require additional analysis to understand. For example, a study of CTE high schools in Connecticut found that the benefits—including higher high school graduation rates and increased earnings—were concentrated among male students, with near-zero effects for female students. Additional research is also needed to understand differing outcomes between within-school CTE models (where CTE programs are offered alongside traditional academic tracks) and whole-school CTE models (where entire schools are organized around career and technical education). A deeper evidence base would en- able policymakers to design more equitable and effective CTE strategies aligned with labor market needs. States and local organizations play a critical role in implementing workforce initiatives. Indiana, for example, estimates that the state will need to fill 1 million jobs over the next 10 years and upskill 2 million individuals to compete in the modern economy. To help address this need, the state operates a “Next Level Jobs” initiative, which provides reimbursement grants ($5,000 per employee) to employers for training employees in in-demand fields and grants to individuals to cover tuition and fees for qualifying certificate programs in the state. Indiana reports that grant recipients increase their earnings by about $7,000 after earning a certificate. Similarly, Virginia’s FastForward program offers affordable, short-term credential programs through the state’s community college system based on the needs of local employers. The commonwealth reports that the credential programs cost about $800 on average, take 6 to 12 weeks to complete, and are associated with a 25 to 50% increase in wages postcompletion. States also prepare students for postsecondary success and career readiness through dual enrollment and the Early College High School initiative managed by Jobs for the Future, a CED partner. For example, in Washington, DC, three high schools offer stu- dents the opportunity to earn up to 60 transferable college credits while still in high school. Local school districts investing in modernizing shop class facilities and pro- grams have also seen high interest from both students and employers. For example, a school district in Bakersfield, California invested $100 million on a new vocational center and Regional Occupational Center helping to fill local employers’ demand for skilled labor. Employers also play a critical role in training workers in the skills they need. For example, in 2022, employers and a trade association in the Pacific Northwest partnered to launch Heavy Metal Summer Experience, a summer program for teaching sheet metal, piping, and plumbing trades through partnerships with local contractors. It has since grown into a national program, projected to serve 900 students across 51 locations, demonstrating opportunities for work-based learning. The National Center for Construction Education and Research also offers employer-led training and certification programs that can be integrated into multiple levels of education (e.g., secondary, postsecondary, and career education). Many employers also offer “earn- and-learn” programs that can be completed while students are enrolled in school. Employers can leverage a variety of incentives to support worker training and education, including partial wage reimbursement for employers who provide on-the-job training to WIOA participants and state-level tax credits or subsidy programs. Identifying and supporting effective models for skill building and job training that do not rely on an employer-centered model of work is also critical. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that about 10% of workers are employed in “alternative arrangements” (typically independent contracting) and younger workers are more likely to be employed in such arrangements. Employment-based training programs should include opportunities for such workers. The federal Pell Grant program has long been a cornerstone of efforts to make post- secondary education more accessible for low-income students. However, the maxi- mum allowable Pell Grant—$7,395 for the 2024-2025 academic year—covers only about 30% of the cost of attendance at public four-year institutions and 60% of the cost of attendance at public two-year institutions. For most Pell recipients, the grant covers about 24% of the cost of attendance. Though most Pell recipients also receive other forms of aid, total aid (including grants, loans, and other assistance) typically only covers about 62% of the total cost of attendance. Since research demonstrates that grants provide substantial economic benefits for low-income students, increasing graduation rates and earnings, Congress should increase the maximum allowable Pell Grant to expand postsecondary access for low-income students. In addition, current eligibility rules largely restrict Pell Grants to students enrolled in traditional, degree-seeking programs, excluding many shorter-term, career-focused training opportunities. Recognizing that many programs do not provide substantial increases in earnings, policymakers should limit eligibility to noncredit workforce training programs at public two-year colleges that result in licensure or certification. With labor shortages already weakening US economic growth and global competitiveness, critical steps must be taken to increase labor supply, prepare workers for the future economy, and attract global talent. Demographic trends, most notably an aging population, are reshaping the labor force, reducing participation rates, and straining key sectors including healthcare and construction. These trends also impact the US fiscal outlook, as a declining ratio of workers to retirees continues to strain government programs. A comprehensive policy response is both urgent and essential.

Trusted Insights for What's Ahead®

Recommendations

Maximize Labor Force Participation

Enact Comprehensive Immigration Reform

Remove Unnecessary Occupational Licensing Requirements

Address Education and Skills Mismatches

Key Labor Force Trends

Pandemic Effects

Aging Population & Immigration

Artificial Intelligence

Policy Approaches

Labor Force Participation

Social Security Retirement Earnings Test

Earned Income Tax Credit

Flexible Work Arrangements

Childcare

Immigration

Strengthening Enforcement

Expanding Legal Pathways

Retain Foreign Graduates of US Institutions

Licensing Requirements

Address Educational & Skills Mismatches

Facilitate Education / Employer Collaboration

Support Career and Technical Education and Workforce Development

Perkins V

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act

Opportunities to Improve Federal Approaches

State and Local Initiatives

Employer Initiatives

Pell Grants

Conclusion

250 Years Forward

January 20, 2026

250 Years Forward: Strengthening an American Future

January 20, 2026

Navigating the Health Care Landscape in 2026

December 01, 2025

US Lead in Public R&D Is Eroding

October 20, 2025

Maintaining the US Lead in Science and Technology

October 20, 2025