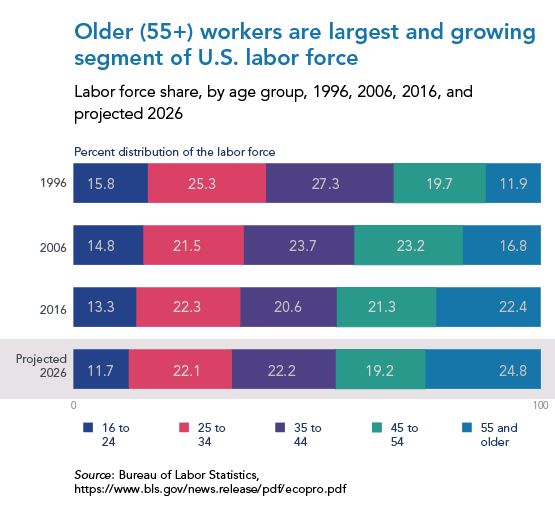

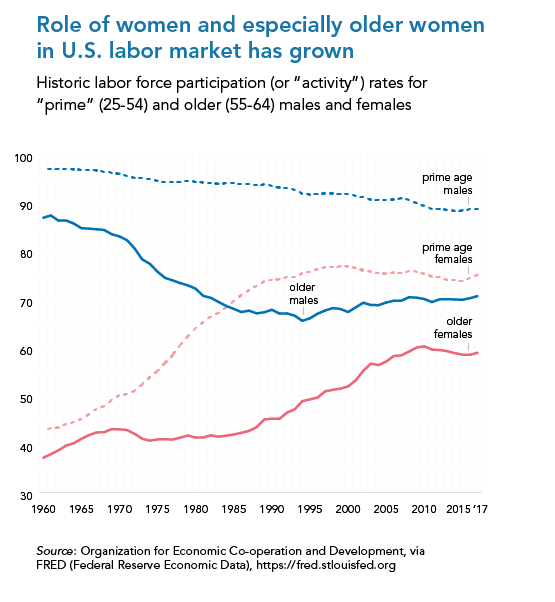

According to The Conference Board’s Global Labor Market Outlook, labor markets continue to tighten with the economy at or near “full employment,” leaving employers having a more difficult time filling positions and retaining workers in certain occupations and industries. At the same time, the long-term demographic trend of an aging population continues, causing both greater demand for certain types of workers (especially in healthcare services), and lower supply of skilled and experienced workers as the baby boomer generation retires. Without much progress on the immigration policy front, the best hope to increase available labor supply is to keep the current workforce engaged in work, particularly the segments of the workforce that are largest and growing: middle-aged, near-retirement, older-than-prime age workers in the 55+ categories: Yet a closer look at labor force trends and projections shows important distinctions between the men vs. the women and lots of reasons why the future of the labor market is (disproportionately) female: 55-64 year old women are a particularly fast growing segment of the workforce and arguably not “past their prime” regarding work. (Full disclosure: I am one of them!) Note that 55-64 female labor force participation rate is now around 60%--as high as “prime age” (25-54) female participation rate was in the late 1970s (when I was in high school). In fact, many of these older women have more time to participate in the labor force now than when they were in their “prime” years and had kids at home (and likely more childcare responsibilities than their spouses did). At the same time, older women are typically more secure financially than when they were younger, so they often have more discretion about how to spend their time. “Work” is not just a job and not just for the money, but something they enjoy for the sense of purpose, social interactions, and continued intellectual growth it provides. For “work” to be more appealing than not working, for the labor market to hold onto these highly-skilled and experienced women, employers will have to let go of the old, cookie-cutter 9-to-5 type of job. In contrast, male labor force participation has been on an overall decline over the decades, and 55+ men still participate at much lower rate than 25-54 men (although the 55+ rate bottomed out in mid 1990s and is now around 70%, still higher than female 55+ participation). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), labor force participation rates over the past decade (2006-16) have also risen faster for 55-64 yr. old women than for 55-64 yr. old men—in absolute (% point gains) and not just relative (% increase) terms. And looking ahead, BLS’s labor force projections show women contributing an outsized role: BLS projects the recent contrast in participation trends between older (55+) women compared with men to extend over the next decade: There is a good confluence of demographic and economic reasons why these projections make sense—why when it comes to the labor market, “the future is female”: In addition, life-cycle factors explain the rise of older women, in particular: Finally, the increase in “flexible” and independent/contract work arrangements make it easier for these older women (and older men as well) to combine work with the rest of what they choose to do with their lives, thus making it more likely that age 55+ women will choose to stay in the workforce when in the past they might have more likely turned down the opportunity to work, if a standard 40-hours/week 9-to-5 job was their only work option. The rise of older women in the labor force is likely already affecting what the “new normal” of “full employment” looks like, and how well (or not so well) we are measuring it. Because older workers often consider themselves as on the cusp of retirement, it is common for them to move in and out of the definition of “labor force participation” depending on how actively they consider themselves as looking for work. Our economy’s true, potential labor force capacity is likely undercounted at any point in time as older workers may periodically yet not permanently self-identify themselves as out of the labor market (not working and not looking for work) and into retirement. As Joseph Coughlin, Director of MIT’s AgeLab, argues in his 2017 book The Longevity Economy: “Often, especially in the 60-plus set, older people who want to work but can’t find any simply say they’re retired. Traditional employment metrics fail to account for this population of would-be workers, which should technically be categorized as unemployed, not retired. And that population is sizable: In one major survey, 40 percent of people who described themselves as retired said they would have preferred to keep on working, and 30 percent said they would jump back into the workforce if the right job opened up.” (pg. 252) So, there are more potential workers out there among the older population and so we might not yet be truly fully at our “full employment” capacity, but competition for these potential workers is still fierce. Given the rising role of older women in the workforce, employers would benefit from a shift in their mindsets and strategies to compete more effectively for them. They must stop thinking that all it takes is more money to attract and keep workers. The plus side from the employer’s perspective is that working women are more willing to trade off flexibility and other non-monetary perks against higher wages (which is one explanation for the gender pay gap), which has kept labor costs relatively low in this latest installment of “full employment” (which has relatively more older women in it than previous versions). In other words, the rise of women relative to men in the labor force—along with the relative increase in female-dominated and generally lower-paying service sector employment—may be one significant reason why wage growth in this economic recovery has not been as fast as expected or what we are used to experiencing. But it’s also a reason why we can think optimistically that the labor market (and our economy’s true capacity) still hasn’t maxed out.

Steady as She Goes Labor Market, Risks Remain

February 11, 2026

Vacancies Plunge, But Low Hire-Low Fire Equilibrium Persists

February 05, 2026

Steady Labor Market Allows Fed Pause

January 09, 2026

Rising Unemployment Augurs More Rate Cuts in 2026

December 16, 2025

Rising Unemployment to Dwarf Solid Payrolls in December FOMC Decision

November 20, 2025

BLS Revises 2024 Hiring, But Not the Labor Market Narrative

September 10, 2025